"They’ll come looking for you"

Soldiers of 131 Divisional Locating Battery, waiting for helicopter transport to FSB Coral on 12 May 1968. AWM P01766.002

As dusk descended over Fire Support Base Coral on the evening of 12 May 1968, some soldiers felt uneasy. They later recalled a sense of foreboding.

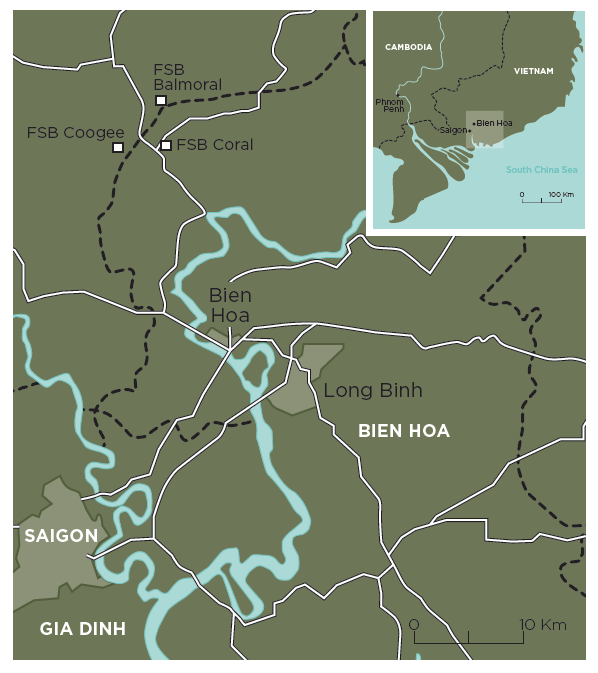

During the day, two Australian infantry battalions, three artillery batteries and support units had moved in to establish the base in an area of operations known to the Americans as “the catcher’s mitt”, 45 kilometres north of Saigon and 60 kilometres north-west of the Australian task force base at Nui Dat in Phuoc Tuy Province. For the 1st Australian Task Force (1ATF), this amounted to a leap into the unknown.

It was known, though, that this area contained enemy infiltration routes used by Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) forces that had attacked Saigon one week earlier during the communist Second General Offensive. The enemy were now expected to use these routes in withdrawing from the capital.

The Australians had been warned that “Charlie” (the Viet Cong) was in the area, but they expected the enemy to be in small groups on the move and trying to avoid battle. This had been the pattern with Viet Cong they had encountered over the previous three weeks. But during a brief reconnaissance earlier that afternoon, Australian soldiers had made a worrying discovery: some 100 freshly-dug enemy weapon pits not far from the site of the base were a clear indication of enemy battle preparations. There were other warning signs too. When the Australian battalion commanders carried out an aerial reconnaissance of the area prior to the fly-in of troops, their US Army pilot would not fly below 2,000 feet and would make only one pass over the area because of the risk of enemy ground fire.

Soldiers of 1RAR patrol "outside the wire" perimeter of FSB Coral between enemy attacks on the base.

Senior commanders also received intelligence reports that North Vietnamese Army main force formations of divisional and regimental size were operating in the area. Battalion commanders later complained of a failure by American and Australian headquarters to pass on this intelligence to unit commanders. For their part, intelligence officers denied there was any breakdown in the passage of intelligence. Whatever the cause, the result was that the enemy threat was underestimated by both soldiers and commanders at the tactical level. Serious concerns about a substantial enemy threat in the area only began to arise after the task force was committed.

Yet the threat should have been obvious by the eve of the operation. After a major contact with enemy forces just two days earlier, the formerly quiet area had become a battle zone on the eve of the fly-in. Units of the US Army’s 1st Division were heavily engaged with NVA forces just three kilometres west of the proposed landing area, causing some delays and diversions during the Australian helicopter insertion.

An ominous warning was given to several Australians by the commander of the American company providing initial protection at the landing zone. “You won’t need to find Charlie,” he said, before departing. “They’ll come looking for you.” The Australians were about to face a much more aggressive, better equipped and well-trained enemy than they had encountered previously during counter-insurgency operations in Phuoc Tuy.

A US Army CH-47 Chinook helicopter delivers stores to 102 Field Battery, FSB Coral, 12 May 1968. Purple smoke indicates the delivery point. At right is one of 102 Battery's M2A2 105-mm howitzers. AWM P01770.010

On 12 May, throughout the hot, humid and dusty day of the insertion, little proceeded according to plan. The fly-in by helicopter was disrupted by delays and there was confusion over the misplacement of some units. National Serviceman Lieutenant Gordon Alexander, artillery forward observer with D Company, 1st Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR), considered the deployment into the landing zone “an absolute debacle”. Units were flown in piecemeal, up to four hours later than planned.

Many soldiers seemed unaware of their correct positions. Major Peter Phillips, commanding D Company, the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), recalled that he had “a confused afternoon because I was never too sure exactly where we were. We seemed to have been landed at the wrong point.”

Artillery batteries were also landed before their supporting infantry, a dangerous practice in potentially hostile territory. At one stage, Captain David Brook, Battery Captain with 102 Field Battery, was deposited in the middle of an undefended, open grassy area selected for the guns – and abandoned there alone for over an hour.

The earlier failure to carry out a low-level aerial reconnaissance of the area led to further problems. The area selected for the fly-in was now found to be covered with low trees and scrub, presenting an obstacle to the helicopters and forcing them to divert some units to another landing zone. Major Colin Adamson, commanding A Company, 1RAR, was dismayed at the confusion and lack of organisation. The battalion was flown into Coral “in dribs and drabs all day” and then, two hours before last light, rifle companies were sent off in different directions to establish night harbour and ambush positions in an arc of up to five kilometres outside the what would become the perimeter of the base.

As night fell over their scattered positions, infantry, artillery and supporting arms were located around Coral in a hurried deployment, intended just to last out the night. The base defences were only partially completed and there was little co-ordination between the dispersed companies and support units. There was no overhead cover on command post and weapon pits, and no claymore mines or barbed wire had been laid to defend perimeters.

Lieutenant Colonel J.J. “Jim” Shelton, commanding 3RAR, felt certain the enemy would attack that night. He ordered his soldiers to dig in. Captain Brook also made his men dig in further during last light, which undoubtedly saved soldiers’ lives. Most men only had time to dig individual “shell scrapes”, less than a metre deep. The gunners of 102 Field Battery had dug their shell scrapes no deeper than 15 centimetres before they were required to “stand to.”

Private Gary Franklin (left) and Lance Corporal Warren Alloway of Australian Task Force headquarters leap into their half-dug weapon pit for cover during an enemy alert at FSB Coral, May 1968. AWM HAL68/0530/VN

At dusk it rained heavily, bringing some relief to soldiers after the heat of the day, but as Bombardier Andy Forsdike of 102 Battery recorded, “all shell scrapes filled with water [and] mud got over everything, later causing numerous weapons to jam.” As companies moved into their night harbour positions at last light, there were fleeting contacts with enemy groups. Sporadic incidents continued which the Australians would later realise were enemy reconnaissance parties probing the base defences, identifying Australian positions by return fire. The NVA also began making preparations for their main attack, forming up and marking their assault lanes.

The Australians did not know that enemy reconnaissance soldiers had observed their insertion and reported to the headquarters of 7 NVA Division, just nine kilometres to the east. The NVA commander resolved to hit the Australians before they had time to settle in. Under cover of darkness and rain, the attacking group – a battalion of 141 NVA Regiment, augmented by 275 and 269 Infiltration Groups – undertook a forced march to close with Fire Support Base Coral; they dug in undetected only 250 metres from the base perimeter.

At about 3.30 in the morning rocket and mortar fire began falling on the base, the heaviest concentration falling on 102 Field Battery and 1RAR Mortar Platoon. Gunner Neil MacNeill of 131 Divisional Locating Battery saw “the arcing trails of a barrage of eight rocket-propelled grenades being launched”. They appeared to come in slowly, gliding in the air for what seemed a long time, before detonating around the base.

This intense fire lasted for five minutes. A ten-minute pause followed. Then, directed by signal flares, North Vietnamese troops rushed the Australian position. One soldier called out to Lieutenant Tony Jensen, second-in-command of the mortar platoon, “There are about 400 nogs [Australian soldiers’ slang for Viet Cong] about 50 yards way.”

The enemy had already reached the base perimeter. Shells from the New Zealanders’ 161 Field Battery were falling outside the perimeter but the artillery close-fire support failed to halt the enemy rush. With communications difficult, Jensen shouted the order to fire his own mortars on maximum elevation and over open sights. But it was too late. He then called out to his platoon to stay underground as he brought in fire in from the 3RAR mortars.

It was now impossible for Jensen to get his men out. As the first attacking wave came in, the enemy was quickly on them, firing into the position and at any shelters still standing. Jensen saw one of the assault troops fire a rocket-propelled grenade into a shell scrape he had just left, blowing his pack to pieces.

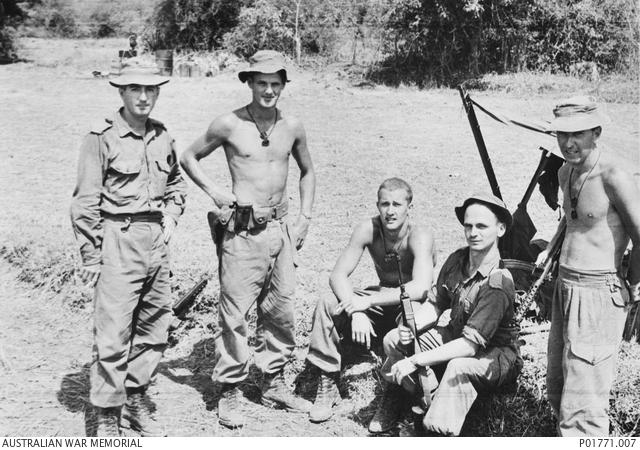

Artillery officers at FSB Coral. From left: Captain Don Tait, artillery officer of B Company, 1RAR; Second Lieutenants Bob Lowry and Matt Cleland, Gun Position Officer Lieutenant Ian Ahearn, and Battery Captain David Brook, all of 102 Field Battery. AWM P01771.007

The main force of the attack, led by several NVA companies, came from the north-east, through the mortar platoon and then on to 102 Field Battery. The initial assault quickly over-ran the mortars as the enemy flank moved through the position at speed. Bombardier Andy Forsdike was lying with his M60 machine-gun team of seven men about 20 metres out in front of 102 Field Battery when the attack began. “VC got up from all around us,” he later wrote, “they had crawled up to within 4 feet (1.2 metres) of the M60 and we did not even know they were there.” The enemy were firing wildly, “holding their AK47s up in the air spraying bullets everywhere”.

"There was yelling coming from the Mortar section – we could hear one of the Mortar Crew yelling that they were coming in and not to fire – then we heard two Australian voices screaming ‘they have got us’ but because of the number of VC between us and the mortars we could not help them – in the end we fired at the VC on the track and we possibly hit the 2 mortar men."

The team continued to fire until their machine-gun jammed. With several men killed or wounded, Forsdike and the rest fell back to the gun positions. One soldier was hit by Australian fire and another two by enemy fire.

The enemy were assaulting in long straight lines of 150 to 200 men. The North Vietnamese had apparently observed the howitzers facing east when they were originally laid. They attacked from the north so the gunners would not have time to adjust fire before they were upon them. The artillery and mortar positions were their principal target. Shortly before the main attack, however, the battery had fired a mission to the north, and the gunners were still standing at their posts. “As luck would have it,” recalled Lieutenant Jensen, “the guns were then facing directly into the line or the direction of the assault.” The gunners began firing over open sights, point-blank into the waves of enemy troops.

As the enemy fought for possession of the mortars, Jensen faced the possibility of his platoon being annihilated. Two men who tried to dash from their pits were killed. In desperation, Jensen saw the only option open to him was to direct fire from the anti-tank platoon’s 90-mm recoilless rifles onto his own position. “Stay down,” he shouted to his platoon through the din of the battle, “Splintex coming in.” He then immediately called for fire. The 90-mm rounds with their thousands of Splintex darts swept across the platoon, clearing everything above ground.

Splintex artillery rounds contained more than 7,000 of these steel flechettes (darts) "which made an awesome sound when going through one's own position", recalled Lance Corporal A.J. Parr. AWM REL35838

On reaching the artillery position, the North Vietnamese overran a howitzer of 102 Field Battery on the extreme edge of the gun line. Another gun was disabled by enemy fire and abandoned. Desperate close-quarters fighting continued between the gun emplacements as the North Vietnamese fought for possession. Lieutenant Ian Ahearn, Gun Position Officer (GPO) with 102 Field Battery, and Captain David Brook later assaulted the gun pit with grenades and regained the captured gun.

Helicopter gunships and fighter aircraft were called in to deliver fire support while a C-47 “Spooky” aircraft circled the base, providing continuous illumination with its flares and hosing the enemy with fire from its multiple mini-guns. By 4.30 am the main enemy attack began to falter. The North Vietnamese withdrew into a rubber plantation to the north-east, taking many of their casualties. Small parties stayed behind to cover their withdrawal. Sporadic attacks continued until dawn but they were broken up in a cross-fire of high explosive and Splintex rounds from both 102 Battery and the anti-tank platoon. The last enemy was located and killed in the Number 6 gun emplacement at 6.10 am.

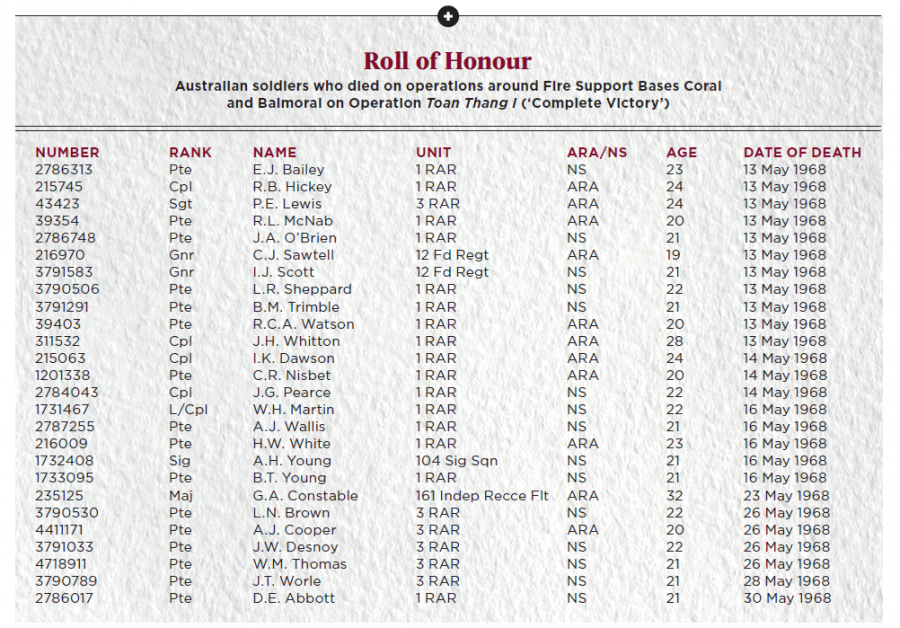

Shortly afterwards, the task force began to evacuate the dead and wounded and to assess the cost of the battle. Eleven soldiers had been killed and 28 wounded. Six of the dead were Regular Army soldiers and five were National Servicemen. Their average age was 22 years. The mortar platoon sustained the heaviest losses, with five soldiers killed and eight wounded from a total strength of eighteen men.

The enemy had left 52 dead, strewn around the fire support base. One North Vietnamese soldier was also captured, along with numerous weapons. Australian soldiers undertook the grisly task of burying the enemy dead in a mass grave near the damaged No. 6 gun. Later that day, Lieutenant Colonel Phillip Bennett, commanding 1RAR, sent a congratulatory message to all units involved in the battle. He commended the soldiers’ steadiness and bravery and noted, “I now believe an enemy battalion has been severely mauled and our losses have more than been accounted for.”

"I now believe an enemy battalion has been severely mauled and our losses have more than been accounted for."

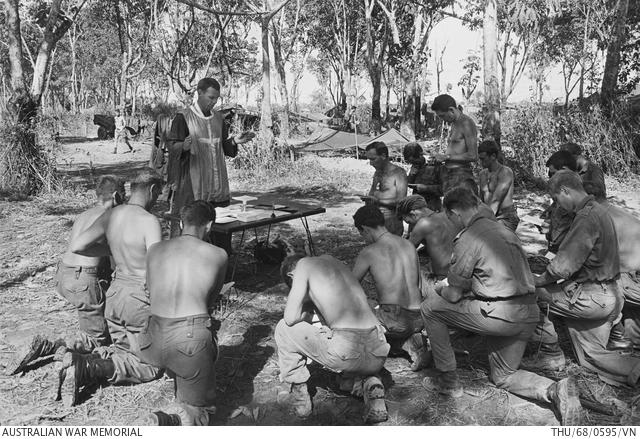

In June 1968, following three weeks of almost continuous enemy engagements around Fire Support Bases Coral and Balmoral, Catholic priest Father R.G. Widdison performs a field mass at FSB Coral to remember the 26 Australians who died and more than 100 wounded. AWM THU/68/0595/VN

Radio Hanoi and local communist propaganda quickly claimed a major victory by 141 Regiment over the Australians. The Australians had no doubt that they had inflicted heavy losses on the enemy – but it had been a close contest. A mortar platoon and two guns of a battery position had been overrun. The attack on Fire Support Base Coral had been the most sustained ground attack on an Australian gun position since the Second World War.

For the Australians, the battle for the fire support base could easily have ended disastrously. Had the enemy rushed the position without the preparatory fire that warned the defenders, the end might have been very different. A degree of luck accompanied the sheer courage and determination of many soldiers in withstanding the massed enemy attacks on the base, and in repelling the enemy. But questions remained over whether soldiers should have been put in this situation – and whether leadership was lacking in the assessment of intelligence, the command and control of the fly-in, and the setting up of the fire support base and its defences.

Operations continued in the area for almost four weeks as the Australians fought some of their largest and most sustained battles of the Vietnam War. In further actions around Coral, and the nearby Fire Support Base Balmoral, they accounted for over 300 enemy soldiers killed. A total of 26 Australian soldiers died and over 100 were wounded. The regiments involved were later awarded one of the five battle honours approved for the Vietnam War. The honour title “Coral” was also awarded to 102 Field Battery, and 34 decorations were awarded to individual soldiers for their actions.

The first enemy attack on Fire Support Base Coral on 12–13 May, however, remained the most hazardous of these engagements – and the most costly. For the first time, the Australians had faced North Vietnamese Army forces in regimental strength. Poorly prepared, they had engaged the North Vietnamese in a pitched battle more akin to conventional warfare than counter-insurgency, and had repelled a massive attack. But many believed their survival owed as much to luck and bravery as to professional planning and command.

Australian soldiers who died on operations are Fire Support Base Coral and Balmoral on Operation Toan Thang I ('complete victory'). ARA/NS: Australian Regular Army/National Service

Further reading: for a detailed account of the battles of Coral and Balmoral, see Ian McNeill and Ashley Ekins, On the Offensive (2003), chapters 12, 13. An evocative account, based largely on the recollections of veterans, is by Lex McAulay, The Battle of Coral (1988).

This article was originally published in Wartime magazine Issue 82. Buy your copy of Wartime from our online shop.