Bringing them in

Indigenous men made a contribution during the Second World War, despite the barriers

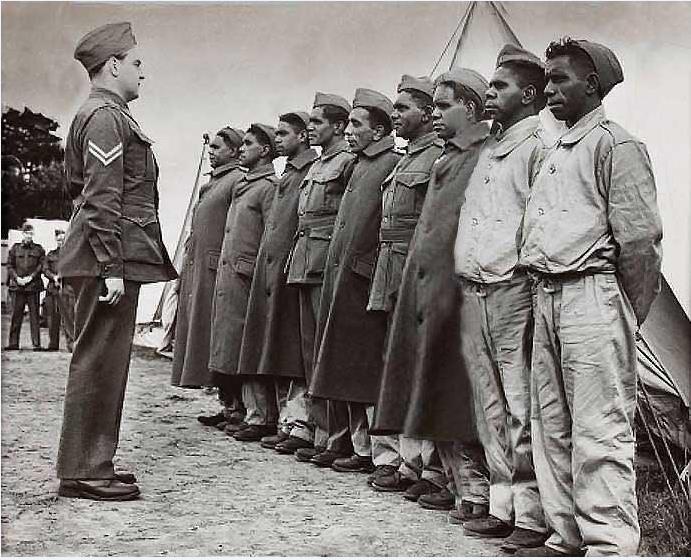

Aboriginal recruits from Lake Tyers lined up for morning parade at Caulfield after joining the 2nd AIF, c. 1940, State Library of Victoria H99.201/282.

“They’re not in the Army as a curiosity,” declared a CineSound newsreel. “They are volunteers in the service of the country they love. They come from Australia’s oldest family. They’ve got a fighting tradition thousands of years old.” In 1940 the “special platoon” raised at No. 9 Army Camp at Wangaratta, Victoria, was touted as “the only all-Aboriginal squad in the AIF” and as “consisting of Aboriginal soldiers, all volunteers”. While they were presented as a group of First Australians successfully joining forces with the white population in a common desire to protect a shared nation, the reality would prove to be very different. The men who enlisted in this “special platoon” – like those who joined similar Indigenous units such as the Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit and the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion – would find their service defined by racial politics.

The second group at Caulfield Military Camp. Herald & Weekly Times, 26 July 1940.

(back row, left to right) Edward Leslie Mullett; Edward Foster; Cedric Parsons; Eugene Mobourne; unidentified; unidentified.

(middle row, left to right) Noel Hood; William Gorrie; Samuel Rankin; Harold Hayes.

(front row, left to right) unidentified; Arthur Mullett; unidentified; David Mullet; unidentified.

The Lake Tyers Mission was established in Victoria’s East Gippsland in 1861 by Church of England missionary Reverend John Bulmer. After decades of violent conflict between the Kurnai people and white settlers in Gippsland, the Mission was intended to provide a home for survivors of the conflict. By the early 1900s, however, the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines believed that Aboriginal people were dying out. The Government of Victoria decided to concentrate Aboriginal people from across the state at the Lake Tyers station, and the board began forcibly relocating “full-blood” and “half-caste” Aboriginal people from reserves at Coranderrk, Ebenezer and Lake Condah reserves to Lake Tyers. Those former reserve lands were carved up as soldier settler blocks for returned servicemen from the First World War, in what was later described as “the second dispossession” of Aboriginal people.

The first group of volunteers for the special platoon enlisted in June 1940. When a second group enlisted in July, The Gippsland Times and the Morwell Advertiser reported, “another large draft of Aboriginals have enlisted in the Second A.I.F.” With over two dozen recruits undergoing medical examinations at the Lake Tyers Mission Station on 13 July, the Gippsland newspapers now noted that it could be proudly claimed that “practically every eligible man of the Lake Tyers Mission Station has joined the A.I.F.” Among the men were Edward Leslie (“Chook”) Mullett, the best ruckman of the Lake Tyers football team; Joe Wandin, a boxer who had travelled extensively in the eastern States with Roy Bell’s team; and Noel Ernest Hood, champion rover of the Lake Tyers football team.

From the First World War

Current estimates are that 1,000 to 1,300 Indigenous Australians fought in the First World War, of whom around 250 to 300 made the ultimate sacrifice. During the early stages of the war, only rarely did the Australian army note on a soldier’s attestation papers whether he was “Aboriginal”; often a simple description, specifying dark complexion, dark hair, or brown eyes, was entered. By the end of 1915, however, it became harder for Aboriginal Australians to enlist. Instructions for the “guidance of enlisting officers at approved military recruiting depots” issued in 1916 stated that “Aboriginals, half-castes, or men with Asiatic blood are not to be enlisted. This applies to all coloured men.” (see Issue 76)

By October 1917, when recruits were harder to find and a conscription referendum had been lost, restrictions were cautiously eased. A new military order stated: “Half-castes may be enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force provided that the examining Medical Officers are satisfied that one of the parents is of European origin.” Regardless of the restrictions in place, Aboriginal men enlisted and served. Some of mixed European parentage enlisted by claiming foreign nationality, while others travelled hundreds of kilometres to enlist after being turned down at centres closer to their communities.

As well as being motivated by the lure of adventure, Indigenous soldiers were paid the same rate as non-Indigenous soldiers – and the pay was good. In general, they served under the same conditions as other members of the AIF, and many experienced equal treatment for the first time in their lives. Upon return to civilian life, however, they found that little had changed. While returned servicemen, nurses and female relatives of deceased soldiers of European descent were able to apply for land as part of soldier settlement schemes, soldier settlement land was not made available for returned Aboriginal servicemen. In Victoria, as former reserve lands were carved up to make soldier settler blocks for returned European servicemen from the First World War, the inhabitants of Coranderrk, Ebenezer and Lake Condah reserves were forcibly moved to Lake Tyers.

Lake Tyers volunteers, waiting for their Second Australian Imperial Forces uniform. Argus, 1940. (front row, front to back) Joseph Wandin; Cornelius Edwards; James Scott; Campbell Johson; William Hayes; Lawrie Moffat; Cyril Scott. (back row, front to back) Rupert Harrison; Otto Logan; Jack Hood; Stanley Harrison; Richard Harrison; Creswick Harrison; Ron Edwards

No time of change

By 1939, Indigenous Australians were divided over the issue of military service. Some believed service would help the push for citizenship rights, and they proposed the formation of special Aboriginal battalions to maximise public visibility. Others argued that Indigenous Australians should not fight for white Australia, as there had been no improvement in rights and conditions following Indigenous service in the First World War. Nonetheless, once again Indigenous men volunteered and served; and in communities such as Lake Tyers, they did so in numbers. A Cinesound News reel made in early March 1941 featured around a dozen of the volunteers from Lake Tyers, described as “the only all-Aboriginal squad in the AIF; original Aboriginal Anzacs”. The “dark-hued diggers” were filmed marching barefoot, swimming, and performing gum leaf music. But despite the positive publicity, their service would be cut short. In 1940 the Defence Committee had decided the enlistment of Indigenous Australians was "neither necessary not desirable", partly because of the belief that white Australians would object to serving with them.

The Australian Aborigines’ League protested against the decision, writing: “The Aboriginal population is intensely loyal to the Empire and the volunteering of the native men is for this reason. They are capable, with good initiative, and I am informed by those training them that they will make excellent soldiers … We have always sought full citizenship, which now includes the right to fight for King and Empire.”

While acknowledging that “some Aborigines and half-castes have been accepted in the past”, the response to this plea was blunt: “Admittance to the army of aliens or British subjects of non-European origin or descent is neither necessary nor desirable.” The Lake Tyers volunteers were discharged on the 24th of March 1941, with notes added to their service records: “Service no longer required – not due to misconduct or discreditable service.”

Of course, this was not the end of recruitment of Aboriginal men over the course of the Second World War. Other men from Lake Tyers enlisted – travelling to other Victorian country towns in order to do so. Three Lake Tyers men who enlisted between February and June 1942 went into the home defence forces, and one into the AIF. All four served until discharged between June 1943 and October 1945.

The experience of the Lake Tyers volunteers is part of the larger story of Indigenous service in the Second World War. Towards the end of the First World War, restrictions against Indigenous service had been introduced and then loosened when recruits were harder to find. In the same way, after Japan entered the Second World War, a growing need for manpower forced the loosening of restrictions. Torres Strait Islanders were recruited in large numbers and Indigenous Australians were enlisted as soldiers and recruited – or conscripted – into labour corps.

“Black diggers” served throughout the Second World War, from the early overseas campaigns of 1940–41 (including the Western Desert, Greece and Crete, and Syria) long before Japan entered the war and brought the conflict to the Australian mainland. Once Japanese forces swept through south-east Asia and occupied territories close to Australia, the Australian armed forces were expanded, with further expansion in Indigenous representation.

While many of those Indigenous Australians who enlisted in the Second AIF found equality for the first time, this equality existed because they were not explicitly recognised as Indigenous. When a unit such as the “special platoon” of Lake Tyers volunteers was defined as “an all-Aboriginal squad”, it was not long before it was disbanded, its service being "neither necessary nor desirable".

Similarly, Indigenous units such as the Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit and the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion found themselves engaged in a form of service that, rather than signalling a movement towards equality and acceptance, echoed the prevailing environment of prejudice and distrust. The NTSRU in particular was viewed by authorities as a form of cheap labour, used to defend Darwin until its replacement by non-Indigenous soldiers.

None of those who served in these irregular units was formally enlisted or paid during the war; formal acknowledgement of their service would not come until around half a century later. Retrospective payment and medals were issued to members of the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion during the 1980s, while similar payments and service medals were not awarded to Aboriginal soldiers until as late as 1994.

About the authors

Michael Bell is a Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man and is the Indigenous Liaison Officer with the Memorial, researching the military service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent. Duncan Beard is an editor at the Memorial.