Victory in the Pacific

Seventy-five years ago, on 15 August 1945, Australian Prime Minister Ben Chifley addressed the country with the following: “Fellow citizens, the war is over. The Japanese government has accepted the terms of surrender imposed by the Allied nations.” In cities around Australia spontaneous rejoicing broke out with wild scenes of celebration. One Sydney resident remembers: “We joined the deliriously happy throng celebrating in the city streets, particularly in Martin Place, which was awash with torn paper, streamers and unrolled toilet paper rolls.”

For those who were fighting and dying in places such as New Guinea or Bougainville, the declaration was greeted more somberly. They had paid little attention to the news, three months earlier, of the collapse of Nazi Germany. Now, with Japan’s surrender, there still was no wild celebration. Many experienced conflicting emotions: relief that the war was finally over, and apprehension for the future. Too many men had seen too many of their friends killed or wounded. On 15 August Private Arthur Wallin, who had first enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in February 1940 and then served in the Aitape–Wewak campaign, admitted in his diary:

[It’s] hard to realize the war is finished when as I write planes are bombing and mortars, artillery and machine-guns are firing. No doubt some think it’s a good idea to get rid of surplus ammunition on the Nip as a final doing over, rather than leaving it to rust eventually.

Lois Anne Martin, centre, wearing the vest she knitted for VP Day in Melbourne, 15 August 1945. AWM P02018.226

Nineteen-year-old Lance Corporal Peter Medcalf, a rifleman serving in an infantry battalion on Bougainville, later remembered: “Strangely no one laughed or cheered. All afternoon we sat quietly and speculated. We found it hard to understand fully.” Writer and future novelist Sergeant T.A.G. Hungerford, then serving in a commando squadron in the mountains of southern Bougainville, recalled similar sentiments:

Suddenly we were unemployed, and suddenly we had to begin thinking about returning to civvy life: and I don’t think there were many who had a very clear idea of what that meant. I know I didn’t.

First contact between the Japanese surrender envoy and Australian forces, Southern Bougainville, 18 August 1945. AWM 095039

Australia’s Second World War lasted six drawn-out years, from 3 September 1939 to 15 August 1945. It was the most destructive conflict in human history. The Allies’ defeat of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and expansionist imperial Japan came at a heavy cost. When the war ended in 1945, parts of Europe, Asia, and the Pacific were devastated, tens of millions of people were displaced, and at least 60 million people, military and civilians, mostly civilians, had died. Although some estimates have put the death toll as high as 80 million.

Australia played its part towards the eventual Allied victory. Almost a million Australian men and women served in the war, and more than half of those went overseas. Australians served around the world: from the deserts of north Africa to the Arctic convoys taking aid to the Soviet Union; from the skies over occupied Europe to the jungles of Malaya and New Guinea. Some 40,000 Australians died in the conflict, while more than 30,000 were taken prisoner. Thousands more were wounded or injured. The Japanese also interned some 1,500 Australian civilians; more than 300 of those were interned in New Guinea, Nauru, and the Ocean Islands. During 1944–45 Australian forces in the Pacific participated in seven separate campaigns: fighting slow, gruelling campaigns in New Guinea and Bougainville, as well as three on Borneo, and contributing to the liberation of the Philippines (see Issue 68). Australian forces were more heavily committed in 1945 than at any other time during the war. Australia’s final campaigns remain controversial, with many questioning their necessity and the justification for what were referred to as “mopping up” operations (see Issue 71).

Australia’s war in the Pacific was part of the wider Allied effort fought against Japan. From 1943 onwards, American ground forces took on an ever-increasing role in the South-West Pacific Area, and in 1944 General Douglas MacArthur’s “island hopping” strategy took American forces from New Guinea to the island of Morotai, in the Netherlands East Indies, and by the end of the year to the Philippines.

Admiral Chester Nimitz’s fleet in the central Pacific was also heading towards Japan with the US Navy and Marines, making a series of costly amphibious landings on Japanese-held islands. Beginning with a landing on Tarawa in November 1943, this campaign stretched well over 2,000 kilometres from the Gilbert and Marshall Islands to the Marianas. From there, American Boeing B-29 Superfortresses were bombing Japan regularly and almost with impunity. By mid-1945 the Allies were close enough to invade Japan’s Home Islands from bases captured in bloody landings on Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Meanwhile, in south-east Asia, Britain’s main effort against Japan was fought to regain Burma. The country’s rugged jungle and monsoon climate made fighting difficult for the British, Indian, Chinese, and African troops – and for their Japanese enemies. Despite fighting defensively elsewhere, in Burma the Japanese remained on the offensive. It was only after huge Japanese losses were incurred at Kohima and Imphal, between April and June 1944, that Field Marshal Sir William Slim’s British force were able to advance. It was in China, however, that the largest proportion of the Japanese army was deployed. Here Chinese nationalist and communist forces fought a murderous war against the occupying Japanese – and each other – for almost a decade (Issue 83). Then on 9 August the Soviet Union began a massive invasion of the Japanese puppet state of Manchuria (or Manchukuo). The Red Army smashed through the Japanese in a huge closing campaign at the end of the war.

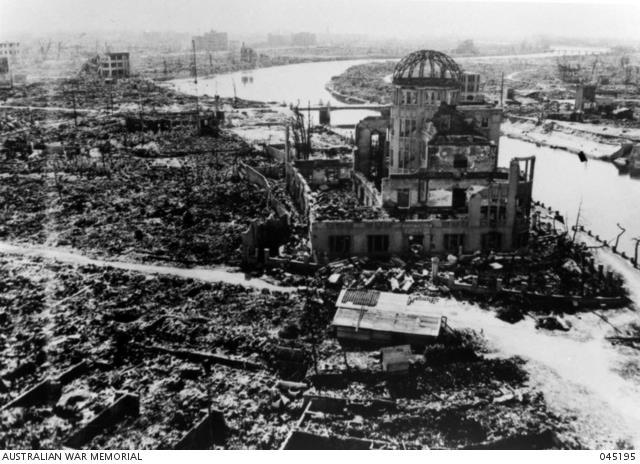

Hiroshima near the blast’s epicenter, 1945. AWM 045195

Choosing the bomb

On the verge of starvation and devastated by American fire bombings, in addition to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August, Japan begrudgingly announced its surrender on 15 August. Many arguments and assertions have been made to explain why Japan lost the war (see Issue 71). In addition to battlefield losses, such as those suffered in Manchuria, proponents of airpower have argued that the American bombing of Japanese cities proved decisive in the Allies’ victory. Alternative arguments hold that the Allied naval blockade cut off mainland Japan from overseas supplies of food and raw material, and crippled Japan’s war economy. Another often overlooked consideration was potential famine due to the failure of the 1945 rice harvest, and the US air force’s targeting of urban industrial areas and the wrecking of the Japanese rail network. Millions of Japanese people may well have died from malnutrition and disease had the war continued into 1946.

More balanced views maintain that there was no single factor that led to defeat: Japan lost the war on all fronts. But as the American historian Richard B. Frank has convincingly shown, it was the dropping of the atomic bombs that finally – and personally – convinced Emperor Hirohito that Japan must surrender. The decision to drop the bombs rightly remains controversial, and the issues relating to this decision have been discussed and debated at length.

Before the bombs were dropped, it was clear that the ruling element within the Japanese government would not accept the Allies’ demands for unconditional surrender, and were prepared to fight to the bitter end. As Frank points out, in late March 1945 Japanese leaders virtually eliminated the distinction between combatants and civilians by declaring all males aged between 15 and 60, and all females aged between 17 and 40 (about 30 per cent of the Japanese population not already in uniform) to be part of a vast national militia. Lacking uniforms and weapons, men and women drilled with sharpened staves or spears. One mobilised schoolgirl was issued with an awl (a hand tool used to pierce holes in wood and leather) with the instruction: “Even killing just one American soldier will do. You must prepare to use the awls for self-defence. You must aim at the enemy’s abdomen.” Such mass mobilisation meant some four or five million Japanese were under arms in the Home Islands, across Asia and the Pacific.

“Operation Downfall” was the codename for the planned Allied invasion of the Japanese Home Islands. It was to consist of two phases, beginning with “Operation Olympic” – the seizure of the island of Kyushu in November 1945 – and followed by “Operation Coronet” in March 1946 to capture Tokyo and Yokohama. In planning papers prepared by the US Joint Chiefs of Staff and Admiral Nimitz, the projected Allied casualties for Operations Olympic and Coronet included 314,619 soldiers killed and missing in the invasions, plus an additional 10,950 sailors, marines, and airmen killed crewing naval vessels and aircraft offshore. Forecasts for Japanese deaths were even higher, both from combat-related deaths or mass suicide as had grimly occurred the battle of Okinawa in April–June 1945. There, in addition to more than 100,000 Japanese military and naval casualties, some 150,000 civilians – half of the island’s pre-war population – died. Had the Allied invasion of Japan gone ahead, it is likely that Australian ground forces would have participated in Operation Coronet as part a British formation.

A clock fused by the atomic blast at Hiroshima. AWM REL/21011.002

At Potsdam

For the few senior officers and officials who were in the know, the atomic bomb was considered the only means to insure a speedy conclusion to the war and save the lives of thousands of Americans. While attending the Potsdam Conference in Germany, on 24 July President Harry S. Truman approved a draft plan to drop the bombs on Japan. The orders were issued the next day, stipulating the use of “the first special bomb” as soon as weather permitted after 3 August. Hiroshima was listed as the first preferred target. On 25 July, the day Truman approved orders to drop the bomb, he wrote in his personal diary of the intention to use what he called the “most terrible bomb in the history of the world”:

Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatics, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare can not drop this terrible bomb on the old capital or the new … The target will be a purely military one and we will issue a warning statement asking the Japs to surrender and save lives. I’m sure they will not do that, but we will have given them the chance.

The next day the Allied powers issued the Potsdam Declaration calling for Japan’s unconditional surrender. No official response was received. Hiroshima was bombed on 6 August: the bomb nicknamed “Little Boy” detonated at 8.16 am. In a blinding white flash, with incomprehensible heat and shock wave, Hiroshima was devastated. Within seconds, thousands of people nearest the epicentre of the blast were vaporised from thermal radiation from the fireball; others had their clothes and flesh ripped from their burnt bodies. Houses, factories and other buildings were flattened, trains overturned. Fire rapidly spread throughout the city. Yamaoka Michiko, then a 15-year-old school girl, was exposed the atomic bomb – making her what is known as a hibakusha. She was badly injured and burnt in the blast:

I felt something strong. It was terribly intense. I felt colors. It wasn’t heat. You couldn’t really say it was yellow, and it wasn’t blue … They say temperatures of seven thousand degrees centigrade hit me. You can’t really say it washed over me … I remember my body floating in the air. That was probably the blast, but I don't know how far I was blown. When I can to my senses, my surroundings were silent … I was under stones. I couldn't move my body. I heard voices crying, ‘Help! Water!’ … They weren’t voices but moans of agony and despair … My clothes were burnt and so was my skin. I was in rags … There were people, barely breathing, trying to push their intestines back in. People with their legs wrenched off. Without heads. Or with faces burned and swollen out of shape. The scene I saw was a living hell.

The next day President Truman delivered a radio broadcast announcing the use of an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. He made this final warning:

We are now prepared to obliterate rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city … Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war … It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of 26 July was issued at Potsdam … If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.

Nagasaki was bombed two days later. It was only after Emperor Hirohito’s personal intervention that the Japanese government decided to surrender. Speaking to his people in a broadcast at noon on 15 August, the Emperor admitted the war had gone “not necessarily to Japan’s advantage”, especially in view of “a new most cruel bomb”.

Figures vary, but it is thought that at least 129,000 people died as an immediate result of the blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As horrific as this figure sounds, more Japanese were killed by conventional bombing than by the atomic bombs. American aircraft bombed 66 cities during the war, and according to Japanese sources 241,000 people were killed and 2.3 million homes were destroyed. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey put the death toll higher, at 330,000, with 2.5 million homes destroyed. The dropping of the atomic bombs, however, brought a sudden and dramatic end to the war and to the fighting in Asia and the Pacific, saving an unknowable number of lives in Japan, Burma, New Guinea, and elsewhere. With the war’s end, hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war and civilian internees were also liberated.

Allied leaders Prime Minister Winston Churchill, President Harry S. Truman and Soviet premier Joseph Stalin, Potsdam, Germany, 25 July 1945. AWM 304804

Surrender

On 2 September, a fortnight after the emperor’s announcement of surrender, Allied warships from the United States, Britain, Australia, and others were anchored in Tokyo Bay while Allied aircraft filled the skies overhead. At the heart of this overwhelming display of firepower was the battleship USS Missouri with its nine 16-inch guns.

That morning a small Japanese delegation boarded the American ship to formally surrender. With General of the US Army and Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, Douglas MacArthur, acting as the master of ceremonies, the Japanese signed the instrument of surrender just after 9 am. MacArthur then signed the document accepting Japan’s surrender on behalf of the Allies. Fleet Admiral Nimitz signed for the United States, and was followed by representatives from China, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, Australia, Canada, France, the Netherlands and New Zealand. General Sir Thomas Blamey, Commander-in-Chief Australian Military Forces, signed for Australia.

The simple ceremony, conducted on the quarterdeck of the imposing warship, took just 23 minutes. “Today the guns are silent,” said MacArthur, “a great tragedy has ended, and a great victory has been won.” He added: “Let us pray that peace be now restored to the world and that God will preserve it always. These proceedings are closed.” Thereafter, surrender ceremonies took place right across the Pacific.

The day of victory acquired several names. In 1945 state governments in Australia gazetted 15 August as a public holiday, to be known as “VP Day” or “Victory in the Pacific Day”. Britain, the United States, and New Zealand, however, preferred “VJ Day” or “Victory over Japan Day”. It has been claimed that in Australia the name VJ Day was changed to be more politically correct. This is not true. In fact, the Australian press referred to the day as “VP Day” from the beginning.

The global security MacArthur and so many others prayed for at the end of the war proved fleeting. The uneasy wartime alliance between the Western liberal democracies and the communist Soviet Union quickly dissolved. By March 1946 a so-called Iron Curtain had descended on Soviet-occupied eastern Europe, while in Asia and Africa nationalist movements emerged to struggle for independence from their European colonial masters. When the peace treaty between the Allies and Japan was signed in San Francisco in September 1951, after the war crimes trials, the US and the Soviet Union were already engaged in a Cold War that lasted for much of the rest of the twentieth century.

Spared from the worst of the conflict’s destruction, Australia prospered in the years following the Second World War. For many Australians the postwar years would present their own fears and challenges, but on the 15 August 1945 – that day of victory – people enjoyed what Prime Minister Chifley simply called “this glorious moment”.

General Sir Thomas Blamey signs the surrender on behalf of Australia as General Douglas MacArthur looks on, Tokyo Bay, 2 September 1945. AWM 040969

VP Day street celebrations in Brisbane, 15 August 1945. AWM P10364.005