Following the bombs down

An Australian served as a film cameraman in Bomber Command.

By Chris Goddard

Flight Sergeant Robert Buckland with his adapted Bell and Howell camera filming the modified crew door. Note the battery box on top the camera. AWM UK2632

The first two years of Robert Arthur Buckland’s military career give the impression of a young man struggling to find his place. Initially mobilised as a gunner with the 9th Field Regiment in October 1940, he stayed with them until March 1941, when he transferred to the Royal Australian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RANVR). Although he was confirmed in the rank of sub-lieutenant on probation at Sydney’s HMAS Rushcutter in November, at the end of May 1942 he failed his exams. There was only one choice left, the Royal Australian Air Force.

Buckland was born an identical twin in 1920 to Arthur and Dorothy Buckland of Bellevue Hill, NSW. Arthur had served in the First World War and probably expected his boys to do the same if another war erupted. Robert and his twin James were educated at King’s School, Parramatta, leading a life of privilege, always referring to each other as “Buckland” and “Buckland Other”, depending on whoever arrived first at a social event. Their younger brother David complained that he was always being left out of the fun, although he followed the twins into the Navy.

Both men were appointed sub-lieutenants in the RANVR in November 1941 and both were engaged to be married. Bob failed his exams, joined the RAAF and married Jill Roberts; but Jim was confirmed in his rank, farewelled his fiancée, and joined the crew of the corvette HMAS Armidale on convoy duty north of Australia. Off the coast of Portuguese East Timor, the ship was attacked by Japanese dive-bombers and sunk. Jim and other survivors tried to make it to Darwin in a Carley float; they were spotted by a Catalina, but disappeared without trace. Jim’s body was never found.

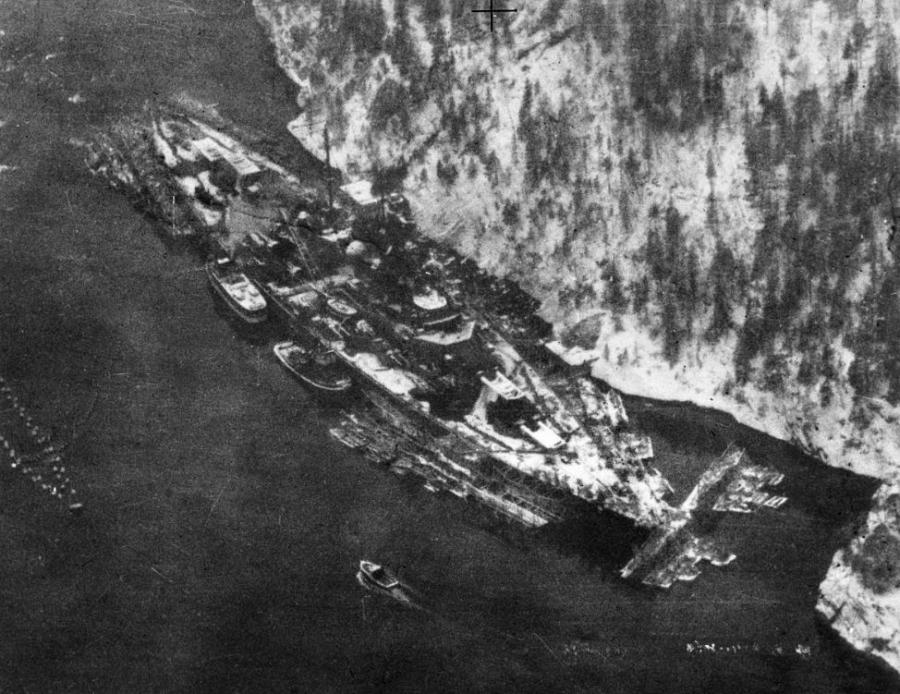

A still of the German battleship Tirpitz in the Tromsø Fjord. Buckland attempted to film the seventh operation against it on 29 October 1944 but Tirpitz was hidden by cloud. AWM SUK11808

Bob Buckland must have felt he had lost half of himself, but the loss appears to have galvanised him and he trained hard. He escaped serious injury himself at No 8 Elementary Flying Training School at Narrandera RAAF Base, when a Tiger Moth struck a parked tender. Trained as a Wireless Air Gunner on CAC Wacketts and Fairey Battles, he was promoted to sergeant just before his departure for service in England on 10 September 1943. He married Jill and they had a mere three days together before he was on a ship to England. Then he was truly on his own.

Film as war

By mid-1941, the Royal Air Force had begun to realise that without its own film unit a filmed record of its role in this vast war, and the resultant propaganda value, were unlikely to be realised. The problems with commercial film companies were already obvious. They were more expensive, ate up valuable time briefing film crews who were ignorant of RAF procedures, and presented security risks while the film was processed at commercial labs. The RAF realised they already had the necessary personnel within their ranks: camera operators, editors, sound technicians and directors.

There may have been an initial coyness about making propaganda, rather than the more genteel “public relations”, but as the war progressed, the British became more hardnosed about this aspect, already exploited brilliantly by the Germans. By the time the Americans entered the war, there were no qualms. This was total war, and propaganda would be part of it.

Thus the RAF Film Production Unit was formed in August 1941. By February 1942 they had set up their headquarters at Pinewood Studios and were already attracting men and women with experience in the pre-war British film industry. By 1943, three operational Film Production Units (FPUs) were active: 1 FPU covered United Kingdom-based operations, 2 FPU dealt with the Mediterranean theatre, and 3 FPU addressed the war with Japan. A fourth unit was formed in April 1944 to cover the D-Day operations.

They were producing and releasing short films and newsreels at a lively rate. They were either straight records of airborne operations, using footage shot by their cinematographers, or more narrative films, using this footage as a part of a more structured, plot-driven film. Either way, they were being used for their intended purpose.

On the ship to England, Buckland had made friends with fellow flight sergeant Peter Newton Steel, a dashing type with a pencil moustache. While awaiting their posting in Brighton, they were offered temporary roles in a RAF Film Unit production about Australians serving with Bomber Command. To the RAF Film Unit, both men were ideal for the role: they were already trained in their basic military roles and protocol, and each had the advantage of good looks and an easy Australian nature – if not acting ability. Both men were temporarily transferred to the RAF to participate in RAAF over Europe. Filming began at RAF Ivor Heath – the air force’s term for Pinewood Studios – in mid-January 1944 for four days, then continued at various RAF bases over the next few months.

Steel and Buckland (under fictitious names) act out the path they were already on: arrival in Brighton, viewing the repairs to bomb-damaged London, allocation to an operational training unit, and their first briefing and flight in a Lancaster bomber. An unknown, tired and laconic Australian briefing officer, in the best-delivered line in the movie, sighs, “Tonight’s target – Berlin … once more”. But the footage used is actually of a raid on Brunswick, not Berlin, taken on the night of 14–15 October 1944, and includes footage taken by Buckland. The scenes with Steel and Buckland were completed in early May. The film was released in Australia in May 1945 and a copy (F01372) is held at the Memorial. Although stirring, it was quickly forgotten with the end of the war.

The Film Production Unit offered the two Aussies further employment and training as cameramen. Steel’s service record contains correspondence dated 11 May 1944: “PR1 Air Ministry, Wing Commander D.N. Twist, would appreciate the services of the two Flight Sergeants who would be used for operational flying as camera men with 2nd Tactical Air Force.” Ultimately, these “two Flight Sergeants” were the only RAAF crew to film with the FPU. After finishing their ground course in “cine camera operating”, they were aerial cameramen – a rare breed in any air force.

The raid on Brunswick of 14-15 October 1943, filmed by Buckland. Still from F02612.

Behind the lines

One of the Film Production Unit’s problems was obtaining suitable cameras, and it was only with difficulty that they were able to source (mostly private) supplies of Bell & Howell and Newman & Sinclair 35mm cameras.

Buckland’s modified 35mm Bell & Howell came to the Memorial’s collection via the Air Ministry in 1946. Commercial versions were driven by a hand-wound spring mechanism, which the FPU replaced with a small electric motor keyed into the cog drive. A battery box contains two original Air Ministry-supplied 1.5 volt B cell batteries (dated to April 1945) mounted atop the drive mechanism, and wired into an on/off switch.

The camera was further enhanced by mounting a 400-foot magazine on the back, enabling the operator to film for 5 minutes without stop. A large reflector lens for filming from height replaces a tubular viewfinder, and the camera uses a single lens mount with a four-inch lens. This series of modifications required the cutting of the metal case to fit the electric motor, but the work is professionally and neatly done.

Finishing his training, but still attached to the RAF with 1 FPU, Buckland was initially assigned to 467 Squadron, a RAAF squadron flying Lancasters out of Waddington, just before D-Day in late May 1944. He was then transferred to 463 Squadron, with whom he remained until April 1945, although for administrative purposes he was moved to 54 Base and later to No 5 Group. By combining the Imperial War Museum’s collection of newsreels in which Buckland is listed as a cameraman, with the 463 Squadron Record Book entries, we can work out the individual missions, the serial numbers of the Lancasters flown, the pilots and the targets.

At least four Lancasters from 463 Squadron were converted in order to be able to provide the camera crew with positions from which they could film. PD329 and PD337 replaced DV171 and LM589 when the latter were lost within two days of each other in September 1944.

The camera Lancasters were converted by replacing the twin machine-guns in the front turret with a special camera mount, called Camera No 1. Camera No 2 was positioned at the rear crew door, which was refashioned to include an open window through which to shoot from a fixed mount or hand-held. A narrow strip of aluminium to deflect the wind was rivetted to the exterior, just in front of the door, to spare the cameraman from being buffeted by the rush of air. Buckland could film from either station. Footage shot in February 1945 of the second Dresden raid notes that there was a third, belly station installed under the Lancaster (Camera No 3), which was likely to have been aft of the bomb bay, where the lower-mid gun turret and later the ground-scanning radar fitting would have been.

The odds

Survival in Bomber Command was low as 40 per cent, and the camera planes were no exception. Two 463 Squadron camera planes had already been shot down. The stress on a crewman’s nerves was traumatic and men learned to cope, or were transferred. Twice, Buckland and his friend Peter Steel (who had filmed with 59 (Liberator) Squadron before being transferred to Lancasters), filmed together. The raid on the U-boat pens in Bordeaux on 13 August 1944 was uneventful, but on their second mission, the night of 29–30 August in the attack on Königsberg, Steel almost fell out of his plane when the pilot took evasive action to avoid a German fighter. Only the door jamming against his back stopped him from falling out.

The accident not only increased the extreme anxiety he was already suffering from (reported as difficulty in sleeping, smoking excessively, crying at night and feeling depressed) but also caused a spinal injury. Steel was returned to Australia towards the end of 1944 and went straight into Concorde Hospital to have his spine fused. He was no longer the smiling man he was when he first arrived in England, leaving Buckland the only Australian with the FPU.

But if you could overcome that fear, as Buckland apparently did, then what you witnessed through your viewfinder was sometimes astonishing. Between 1.30 and 1.55 pm on 17 September 1944, Buckland and Oakey, a British cameraman, filmed the paratroop jump which formed the opening phase of Operation Market Garden, which ended in defeat for the Allies on 25 September. The jump, involving 20,000 troops, was unopposed. For those calm 25 minutes, Lancaster DV171 flew at between 2, 000 and 2,500 feet, leisurely filming the endless lines of parachutes.

On 29 October, Lancaster PD329 travelled from Lossiemouth in Scotland to the Tromsø Fjord to cover the attempted bombing of the Tirpitz, the seventh of eight airborne attacks on this target. It was proving a hard target to hit, let alone sink, and so it was on this raid. Buckland was accompanied by Loftus, another British member of 1 PFU, but the cloud cover prevented good images from being taken and only 150 feet of film was exposed. Still, the view from 8,000 feet and the sight of the 5,400 kg Tallboys exploding all around the Tirpitz must have been highly impressive.

The details of these two operations also make it clear that, although the majority of missions were flown to cover their own squadron’s operations, when required either of the 463 Squadron camera planes could be pulled aside to perform special duties, especially where the performance and range of a four-engined Lancaster were required. Although they were 463 Squadron’s aircraft, these were Film Production Unit aircraft as well, and often flew as a single camera plane accompanying other squadrons’ missions.

This occurred on four occasions: the paratroop drop on 17 September 1944 in DV171 piloted by Flight Lieutenant Garden; the attack on the Tirpitz on 29 October 1944 (in PD329 piloted by Flight Lieutenant Buckram); a daylight attack against the synthetic oil tanks at Kamen on 11 October 1944 by 3 Group (PD329 piloted by Buckram); and the raid by 617 Squadron on the railway viaduct at Arnsberg on 19 March 1945 (PD329 piloted by Tom Perry). This last raid was also conducted with Tallboy bombs, “From the front I covered the release of the bombs and followed them down,” commented Buckland on their return. The navigator added that when the bomb hit, “debris came up at least 6,000 feet in the air.”

Robert Buckland covered operations including D-Day, Operation Market Garden and the bombing of the V1 sites at Beauvoir. AWM UK2633

Pilots

The men on whom the cameramen came absolutely to rely were the pilots of these planes. Whether flying in formation in a group of 796 Lancasters (in the case of the second Dresden raid) or piloting solo for 3,624 km across the North Sea and back for the Tirpitz attack, the pilots held eight lives in their hands.

In his 30 missions (totalling 187 hours of flying) for the Film Production Unit, Buckland came to rely on nine pilots who had to handle an overloaded plane (the cameramen were carried in addition to the crew) and often carried a bomb load as well. Six of these men were decorated, or would soon be.

Buckland would tell his son stories about the seven missions flown by Flight Lieutenant Fred Merrill, DFC, on D-Day, when they bombed the railway network at Argentan, and were fired at on both the outward and return journey by some jittery Allied naval forces in the Channel. He piloted the camera planes during operations to bomb such targets as the V1 flying bomb sites at Beauvoir (29 June) and Bois de Cassen (2 August); the attack on German positions on the Villers Bocage front on 30 July; and a night attack on the oil depot at the U-boat pens in Bordeaux on 13 August: each of these with all the attendant dangers.

Later Buckland flew six missions with Flight Lieutenant Bruce Buckram, who won a Distinguished Service Order for his work on “photographic sorties” in addition to his DFC. As well as flying one of three missions with Buckland to cover the various raids on the Tirpitz, he piloted DV171 for the attack on German positions at Calais (a daylight raid) and the daytime attack on Duisberg on 14 October in the new camera plane, PD328.

The other pilots Buckland flew with were Flight Lieutenant Mel Skelton (five missions in PD329 and PD337); Flight Lieutenant Keith Schultz, DFC and bar (four missions in both PD329 and PD337); Flying Officer Tom Perry and Pilot Officer Sam Johns, DFC (two missions each, Johns flying with 467 Squadron), and also Flying Officer Ray Hattam, DFC, Wing Commander Rollo Kingsford-Smith DFC and Flight Lieutenant Roy Garden, DFC (one mission each).

The society pages in Australia kept up with the intrepid Buckland, and now form part of the Australian War Memorial’s collections. When he completed his 30 mission tour in early April 1945, the war in Europe was almost over. To fill in the time while he waited for a place on a ship to Australia he joined the RAAF relay swimming team. On Thursday 3 January 1946, Jill Buckland reported to Sydney’s Daily Telegraph that she expected her husband “tomorrow”. Flying Officer Buckland was discharged from the RAAF a few weeks later. There is no evidence that he ever continued his role in cinematography.

To read Chris Goddard’s article, you can purchase your copy of Wartime here.

About the author

Chris Goddard is a curator in Military History and Technology. He is working on the upcoming exhibition “Action!”, about the role of people, cameras and film in Australia’s wars.