The river and the redoubts

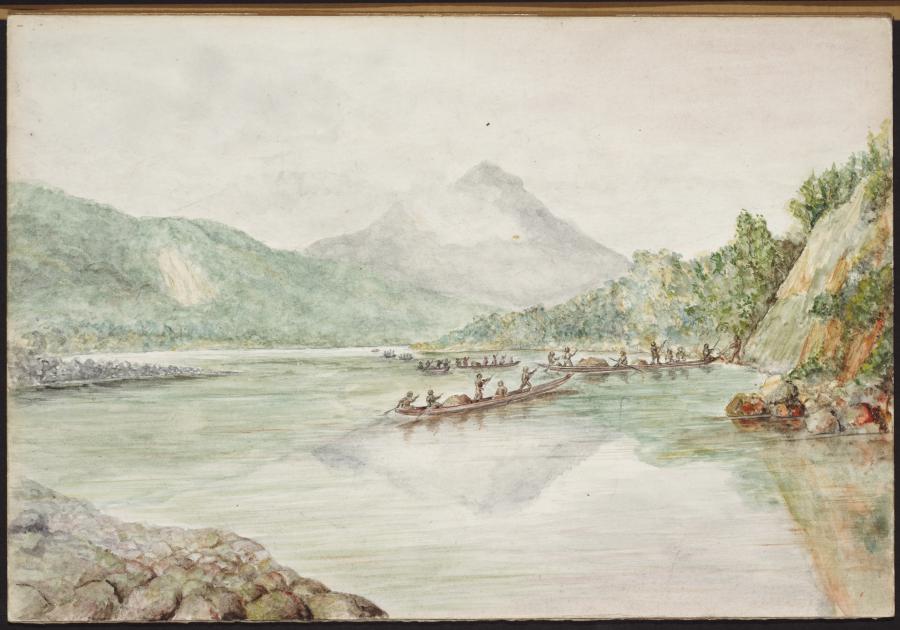

Thomas William Downes. Major Brassey at Pipiriki, 1865 (watercolour, 21 x 31 cm). Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, A-076-013.

While most of Australia’s military history focuses on our involvement in major conflicts such as the world wars and Vietnam, over the past century and a half Australians have also fought in less well-known wars all around the world. Men and women from Australia or its former colonies have fought in far-flung places from North Russia to South Africa, from Sudan to Spain and Azerbaijan. They also have fought much closer to home.

The New Zealand Wars between 1845 and 1872 were fought over two main issues: land and sovereignty. Deceived by the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, the Māori chiefs who signed it believed they were not ceding sovereignty or land rights. But to the colonists they had, and as more and more settlers arrived, that rapidly became all too apparent. The Northern War broke out in 1845 at Kororāreka (today’s Russell), followed by outbreaks of fighting around Wellington and Whanganui. Then, after a pause of several years came the First Taranaki War of 1860–61. Everywhere, it seemed, the Māori were under increasing pressure and losing their lands and control of their affairs.

Australian involvement

During the earlier campaigns, the Australian colonies’ military involvement was largely confined to releasing British Imperial regiments for service in New Zealand. The sloop HMCS Victoria also participated in the First Taranaki War (See: The first ship of war).

Following the outbreak of the Second Taranaki War in April 1863 and the invasion of the Waikato in July, the New Zealand government sought additional troops for military operations, and to occupy and settle the conquered lands. In July and August 1863 recruitment began in Otago and in the Australian colonies. Ultimately, some 2,500 men from the Australian colonies signed up for New Zealand’s military settler scheme. After three years’ paid service they would be entitled to settle a block of land.

During a second recruitment in Melbourne in January 1864, among the new enlistees was James Frisby Wilkinson. His letters home during his service in New Zealand are some of the oldest personal papers in the Memorial’s collection. He was a 27-year-old printer living in Melbourne when he volunteered as a military settler for New Zealand. With prior military service in the Pentridge Company of the Victorian Volunteer Rifles, he was known as a crack shot; he joined the Taranaki Military Settlers and was soon in New Plymouth on the Taranaki coast. By 1864 the Taranaki Military Settlers had ten companies and nearly 1,000 men, and settled into garrison duty, protecting outposts and guarding supply routes in the region. In early 1864, the 8th and 10th Companies were shipped down the coast to the town of Whanganui where more trouble was brewing.

Taranaki Military Settlers circa 1865. Photographer unknown. Puke Ariki Taranaki Museum and Library, PHO2008-1859

The Hauhau

Fighting had broken out again in Taranaki in April 1863, and over the next three years it spread throughout the region and Manawatū–Whanganui. Concurrent campaigns were waged in the Waikato and Tauranga on the east coast, and by 1864 the Māori were defeated or dispersed on all fronts. As a response, the so-called Hauhau Movement emerged, an extremist group adhering to the Pai Mārire religion – a syncretic blend of Christianity and traditional Māori beliefs – who would fight to the death. Now the fighting took on a much more menacing tone. As historian James Cowan described, the Hauhau, driven by incantations and a “belief in supernatural protection from bullets” would employ terror tactics including “beheadings, the removal of the hearts of enemy and cannibalism”.

Hauhau leader, Chief Topia Pehi Turoa after the war. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. AColl-5671-42

Whanganui Campaign

The colonial government’s next priority was to open up road communications and land for new settlers along the southern Taranaki coast between New Plymouth and Whanganui. At the beginning of 1865 military operations began in support of these goals. Further inland, up the Whanganui River, a new threat had emerged. Upriver tribes hostile to the government included many who had joined the Hauhau Movement. Their forays down river could provide reinforcements for southern Taranaki and also threaten the settlers and allied Māori on the lower river and the town of Whanganui on the coast. This threat had to be blocked.

The previous May had seen the first attempt thwarted at the Battle of Moutoa Island. The Lower Whanganui Māori, friendly to the government and settlers, had sent a war party upriver to meet an enemy incursion. The fight was quick and brutal; the defeated Hauhau withdrew upriver. But they would be back, so it was decided to send a force of militia and allied Māori to garrison Pipiriki, a small village some 70 km upriver.

Pipiriki

The upper Whanganui was described by one observer as the most difficult part of New Zealand for military operations. The terrain was semi-mountainous and cleft by the great river itself. Ravines in the 30-metre rock cliffs cut the banks at numerous points, providing small patches of level farming ground. Beyond the river banks and cliffs rose steep hills and densely forested mountains. Pipiriki lay at a bend in the river, a narrow point where the hills closed in, making it easy to dominate traffic. There was a Māori village, a church mission school, and a flour mill.

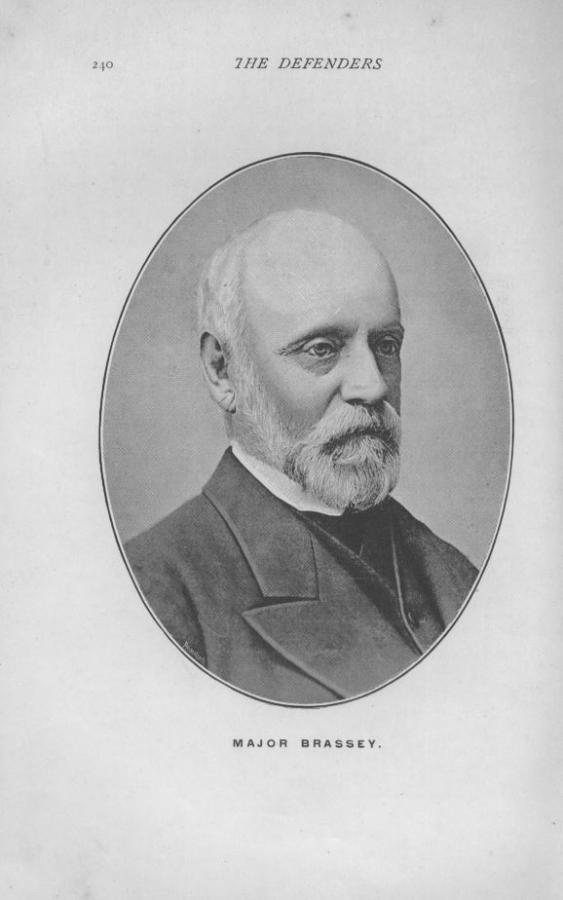

The force sent to Pipiriki, totalling about 300 militiamen, arrived at the end of April 1865. It consisted of Nos. 8 and 10 Companies of the Taranaki Military Settlers under Captains T. Wilson and D. Pennefather; a company of Patea Rangers, and a contingent of Lower Whanganui Māori. The overall commander was Major Willoughby Brassey, formerly of the Royal Navy and the East India Company, and a veteran of the wars in India and Afghanistan.

Major Brassey. From The Defenders of New Zealand, T.W. Gudgeon (1887). Courtesy of Early New Zealand Books, Te Tumu Herenga, University of Auckland.

The men soon got to work, building three redoubts (temporary enclosed earthwork fortifications) upon low knolls on the right bank of the river. No. 1 Main Redoubt was in the centre near the village; No. 2 ‘Popoia’, a few hundred metres to its north; and No. 3 ‘Gundagai’, a few hundred metres to the south. The weak points in the defence were the nearby hills which overlooked the redoubts, as well as an unoccupied knoll between No. 1 and No. 3 Redoubts, which was also higher than the redoubts. It lay unguarded because it was a Māori burial ground and Brassey had been assured none would venture up there.

Map from The New Zealand Wars, Vol. II by James Cowan (1922), p. 519

Not long after arriving at Pipiriki, Wilkinson wrote to his cousin:

We do not live so badly. The rebel natives are holding a pah some 12 miles up the river, but I don’t think any move will be made this winter to drive them out ... If the rebels should come, we are prepared to give them a warm reception.

The weeks passed and nothing happened. Boredom, discontent and ill-discipline began to set in – as did the consumption of rum. The force was then weakened by the departure of their Māori allies, called away to help in the attack on Weraroa pā in southern Taranaki. This reduced the garrison by about 60 men.

The Hauhau make their move

As soon as the Hauhau discovered the militia had occupied Pipiriki, they resolved to destroy them. Their leader in this locale, Chief Topia Pehi Turoa, had been captured earlier in the year, but released upon an oath to desist. He quickly broke his pledge – the occupation of Pipiriki by the hated pākehā (white man) was seen as a challenge and an intolerable provocation. It took several weeks to assemble a force from all over the Upper Whanganui, but by mid-July they had around one thousand warriors. It was time to make their move.

Early on the morning of 19 July an officer who had strayed from camp inadvertently sprang an enemy ambush. Pursued by tomahawk-wielding Hauhau, he was lucky to escape and alerted the garrison. Attacking en masse, the enemy warriors soon penetrated the defences and established strong parties between No. 1 and 2 Redoubts, and on the burial ground knoll between Nos. 1 and 3. From the latter they began to pour fire down on the militiamen. Many more Hauhau from the surrounding hills and ridgelines kept up a constant fire as well. The garrison was very suddenly in dire straits.

Brassey ordered Lieutenant H.A. Clery to take a detachment of men and drive the enemy off the burial ground knoll. With covering fire from the other redoubts they immediately climbed the steep hill, battling through dense scrub and stormed the enemy with the bayonet. The Hauhau fled and the militiamen occupied the hill, manning the rifle pits their foe had begun digging.

Wilkinson captured some of the action in his letters:

On the morning of the 19th, at 8 o’clock, the Maories in a body of some forty or fifty came over the river in canoes, and taking cover on Cemetery hill, opened fire on us, in the Gundagi Redoubt. Cemetery hill position quite commands Gundagi. At the same time a large body of Natives opened fire on the Bushrangers and Centre Redoubt.

The firing continued all day and morning of the next, the bullets flying through the tents in all directions. We all held our own in gallant style, returning the fire, where we saw it was advantageous. At 2 p.m. Ensign Cleary and 20 volunteers from the main camp advanced across to us (Gundagi) and under our covering fire, gallantly charged up Cemetery Hill, and drove the enemy before them, shooting 2 rebels and capturing a rifle.

James Frisby Wilkinson after the war. AWM, P10416.001

With the immediate danger over, the battle continued at longer ranges. From the commanding heights of the nearby hills and surrounding points on both sides of the river, the Hauhau kept the garrison under constant fire. Brassey ordered the church dismantled and the timbers used to reinforce the redoubts, providing some overhead cover.

The standard militiaman weapon was the Pattern 1853 Enfield, a muzzle-loaded rifled musket with an effective range of around 600 metres, more in the hands of a skilled marksman. Their opponents likely had some similar weapons, either captured or traded, but most would have had an assortment of less effective firearms of older vintage.

As the siege wore on day after day, the garrison’s supplies dwindled, including ammunition. In order to conserve ammunition, the best marksmen were called upon to do most of the firing. As Cowan described:

Sometimes a reckless fanatic would leap on to a parapet showing on the hillside, and yell Hauhau chants and battle-cries. A prophetess, who apparently believed that her Atua Pai-Marire had given her immunity from bullet-wounds, was conspicuous in front of one of the entrenchments on the high ground above the redoubts. She paraded up and down, chanting her songs, and cheering on her warriors with cries of “Riria, riria!” (“Fight on, fight on!”) Marvellously she escaped death many times. Sergeant Rushton, after an unsuccessful shot, said to his comrade Sergeant McDonald. “I was low; try her at full 400 yards.” The marksman fired, and Rushton, watching through his glasses, saw the warrior chieftainess fall.

James Wilkinson was also called into action to deal with an enemy sniper firing from a house on the far side of the river, some 330 metres away.

After waiting for half an hour for a slant, I popped a bullet through my Gentleman’s port hole, which frightened him into quietness for the rest of the night. I have heard since from the Cemetery Hill chaps, who had a partial flank view, that they saw him skedaddle by the rear just after my shot.

One of Wilkinson’s letters home during the Siege of Pipiriki, July 1865. AWM, PR04406

Each night the enemy warriors would gather, their chanting and war cries punctuated by barking “Hau, hau!”and the sounding of bugle calls on their homemade trumpets. Although relatively safe in their redoubts, the garrison was pinned down and the supply situation steadily worsened. Brassey needed to send word downstream for help and wisely resorted to a variety of methods. A Māori ally was paid a hefty sum to carry a note through enemy lines; later two rangers were also sent by canoe. More innovative were the messages floated downriver in two bottles, one in French, the other in Latin. At least one, and perhaps all these methods worked. Help was coming.

By 25 July a force of 300 men including Forest Rangers, Whanganui Bush Rangers, and a Māori contingent set out from Whanganui. Reaching Hiruharama (Jerusalem), they awaited reinforcement by a further 500 allied Māori who arrived a few days later. On the 29th they set out in canoes for Pipiriki.

Curiously, Hauhau peace overtures saw Lieutenant W. Newland escorted upriver to meet with Pehi Turoa the night of the 29th but no capitulation ensued. Newland was extremely fortunate to be returned unharmed to Pipiriki, as was the Hauhau hostage upon whose life Newland’s fate also depended.

Next morning as the sun was rising the relief force rounded the bend in the river and came into sight, the warlike songs of the Lower Whanganui booming as they strained at their poles and paddles. Soon it seemed the river was alive with canoes and salvation was at hand. The next morning, the Hauhau abandoned the siege and retreated north. Wilkinson wrote:

Relief has come to us from town, which has gladdened all hearts. Fearful accounts were spread about us ... It was said 50 of us had been tomahawked ... and the rest were all starving in the main camp … The men on Cemetery Hill burst out cheering, which was caught up by the Bushrangers and ourselves, in the main camp, - “Relief”, that cheering word to the distressed soldier, was echoed on all sides. The Maorie militia and a number of volunteers were the first to arrive in their canoes, closely followed by von Tempskie’s Forrest Rangers.

The relief force pushed further upriver and the main Hauhau camp at Ohinemutu was burned and their crops destroyed. During the twelve-day siege at Pipiriki casualties had been remarkably light. Of the militia garrison, none was killed and only a handful were wounded. Even Hauhau casualties were minimal, with around 13 killed and perhaps the same number wounded. For their gallant defence of Pipiriki, Brassey’s force received Governor Grey’s written commendation.

Photo of roughly the same vista as in the Downes artwork. Taken by the author in 2011.

War Continues

Wilkinson and the Taranaki Military Settlers remained at Pipiriki until the end of August when they were despatched on the East Coast Expedition. There they saw further fighting to avenge the gruesome and barbaric murder of the Reverend Völkner at Opotiki in the Bay of Plenty. An indiscriminate punitive operation followed, culminating in an attack on Omaruhakeke Pā on Christmas Day 1865.

By the middle of 1866 peace had been achieved between the Upper and Lower Whanganui tribes, while government forces continued their conquest of southern Taranaki. After 1866 the involvement of British Imperial forces in New Zealand declined and the militia took over what fighting remained. The following year, 1867, the Colonial Defence Force, including the military settler regiments were disbanded and replaced by the formation of the New Zealand Armed Constabulary, which combined military and policing roles. Some militiamen, including Australians, transferred to the new force and continued the war against what remained of Māori resistance. Increasingly the war became a guerrilla affair of hit and run tactics and lengthy pursuits through remote areas. Pai Mārire adherents and other groups determined to resist the pākehā takeover followed charismatic leaders such as Titokowaru and Te Kooti over the next few years until the latter’s resistance finally ended in 1872.

James Wilkinson completed his service in New Zealand but like so many Australian volunteers either didn’t take up the block of land he was entitled to, or soon sold it and returned to Australia. Conditions for the military settlers were tough and the land they were given was often very rough and poor. With their three-year enlistments up and service pay ceased, many were left with no viable income and the government did little to help sustain them. Additionally, the prospect of living on the newly conquered frontier, close to still hostile Māori, probably influenced the decisions of many not to stay.

Wilkinson returned to Melbourne and married in 1869. He resumed his service with the Victorian Volunteer Rifles, eventually becoming a captain in the Northern Rifles. He died prematurely in 1882, at age 46. His letters give us a rare insight into a little-known war in which Australians fought, and an even more obscure campaign. One of Queen Victoria’s so-called ‘little wars’, the conflict in New Zealand was just one of many fought to conquer distant lands and peoples, and expand the power and prestige of the British Empire.

Some may see the service of Wilkinson and the Taranaki Military Settlers as the beginning of a proud tradition of Australian–New Zealand military cooperation. While true, others may view it as somewhat mercenary: paid to dispossess a native people of their land and settle it themselves. History and the truth are often contested ground as well, and sometimes uncomfortable.

While there are some differences in the conflicts between the indigenous inhabitants of New Zealand and Australia and the British colonists, there are many more similarities. The 27-year conflict in New Zealand has always been referred to as a ‘war’ – even the latter years when it became more of a guerrilla war and a ‘policing’ affair. In Australia, sadly, resistance continues to acknowledging what happened here as the ‘Frontier Wars’.

About the Author

Craig Tibbitts is a senior historian at the Australian War Memorial, where he has worked since 2000. He has made several trips to battlefields of the New Zealand Wars, including Pipiriki in 2011.

Further Reading

Letters of James Frisby Wilkinson, Australian War Memorial, PR04406

The New Zealand Wars / James Cowan (two vols. 1922–1923)

Blood Brothers: The Anzac Genesis / Jeff Hopkins-Weise (2009)

Australians at War in New Zealand / Frank Glen (2011)

The New Zealand Wars / Vincent O’Malley (2019)