Remembering Australia’s Second World War

An unidentified sailor from HMAS Perth with his family, Sydney, 31 March 1940. The light cruiser saw extensive service in the Mediterranean before being sunk in the battle of the Sunda Strait in 1942. Survivors spent the rest of the war as prisoners of the Japanese.

One of the men leading the Veterans’ March in Canberra on Anzac Day this year was Les Cook. The 99-year-old was not riding in a vehicle but led the march on foot as it moved through the grounds of the Australian War Memorial, past the Governor-General of Australia, David Hurley, and the Stone of Remembrance. Cook had enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in 1940 when he was 17, and served in the Middle East, Papua, New Guinea, and Borneo. When asked by a journalist to reflect on his wartime service, Cook remarked,

We weren’t soldiers, we were heavily-armed civilians ...Yes, there were some who were heroic and some who were extraordinary, but for the most part, we were just ordinary people.

Being in the Memorial grounds on Anzac Day 2022, I am certain that the applause from the crowd watching the march increased as they caught sight of the elderly veteran with a big smile walking past them, and when he appeared on the large screens showing the televised broadcast of the proceedings. Those watching applauded Les Cook. They were applauding his generation of Australians who had fought the Second World War.

I have argued previously in Wartime (no. 71) and elsewhere that the Second World War was the conflict that most shaped Australia during the 20th century. It was the country’s largest ever conflict and one of the most significant. Nearly a million Australians – including Les Cook, his father who had also fought in the First World War, and many others, such as my paternal grandfather and his brother – served in the armed forces during the war. More than 30,000 Australians became prisoners of war (8,500 prisoners of the Germans and Italians; 22,000 prisoners of the Japanese), and some 40,000 died while serving around the world with the army, the Royal Australian Air Force, the Royal Australian Navy and the Merchant Navy.

Members of the Rats of Tobruk Association among the crowd attending VP Day celebrations in Sydney. 16 August 1945.

The Australian economy, industry and society were likewise mobilised for war. The federal government assumed unprecedented control over the daily lives of Australians. Everyday regulations and controls in 1939–45 were far stricter than the inconveniences many of us experienced during the Covid-19 lockdowns and shortages of 2020–21. During the war years, large numbers of Australian women moved into non-traditional roles and trades in the workplace and the military. For the first time too, hundreds of thousands of Australians travelled and experienced the different peoples of Oceania and Asia. Australia emerged from the Second World War industrialised and confident, with a sophisticated relationship with Britain, a new friendship with the United States of America, and ready to engage with Asia and the Pacific. Post-war emigration from Britain and war-torn Europe to Australia helped the economy to boom and the population to diversify.

Shaping public memory

The Second World War was the bloodiest and most distructive conflict in human history. At least 70 million people died. The consequences of the conflict, such as the Cold War and de-colonialisation in Asia and Africa, were felt for decades. Little wonder then that the war has been celebrated, studied, imagined and continually re-interpreted ever since 1945. In recent times, during the Brexit debates we have seen the myth of “Britain alone in 1940” heavily politicised to support leaving the European Union; and similarly, the Red Army’s bloody contribution to the defeat of Nazi Fascism has been weaponised in Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

As has occurred elsewhere, the significance and understanding of Australia’s involvement in the Second World War have evolved, though thankfully not to the same extremes. We need to be clear about what is meant by memory and remembering in a public context. Remembering the war is more than hearing grandad’s stories or reminisces; rather, historian Joan Beaumont has defined public memory as remembering through public ceremonies and events, memorials, publications, and other forms of official acknowledgement or commemoration.

In the years immediately after the 1939–45 war, and when Les Cook participated in his first Anzac Day march in 1950, it was the Rats of Tobruk who were the most prominent veterans of that war. Having withstood the German Desert Fox, Lieutenant General Erwin Rommel and his Afrika Korps during the siege of Tobruk in Libya during 1941, the defenders of Tobruk won fame amongst the Allies and formed an influential worldwide association. They included Australians, British, Indians, Poles, and Czechs. Many of these units went on to defeat Rommel a second time, during the pivotal second battle of El Alamein in 1942.

Australian Tobruk veterans were celebrated in countless novels, books and films such as Charles Chauvel’s The Rats of Tobruk (1944) – as well as in public memorials like the Tobruk Memorial Baths (1950) in Townsville, north Queensland, and the Rats of Tobruk Memorial (1983) on Anzac Parade in Canberra. Two Australian RAN ships have been named HMAS Tobruk, and the association was very active in supporting community causes and philanthropy. It was the Rats of Tobruk who came closest to rivalling the original Anzacs who fought on Gallipoli during the Great War in 1915. It was no coincidence that two of the principal characters in Alan Seymour’s then-controversial play The one day of the year (1958) were Gallipoli and Tobruk veterans.

Department of Aircraft Production building Beaufort bombers at Fisherman's Ben, Melbourne, 15 June 1943.

It was not until the 1980s that the Pacific war really began to dominate Australian narratives of the Second World War. Two notable precursors, however, were Russell Braddon’s The Naked Island (1951) and Betty Jeffrey’s White Coolies (1954). Both authors had been prisoners of war held by the Japanese, and both memoirs were very successful and frequently reprinted. Thirty years later, journalist Tim Bowden and historian Hank Nelson used oral history interviews with surviving former prisoners of the Japanese to tell their own experiences of captivity, brutality, and humour, in a powerful ABC Radio series. This program and the subsequent book, POW: prisoners of war: Australians under Nippon (1985), along with the publication of Sir Edward “Weary” Dunlop’s war diaries from the Burma–Thailand railway (1986), engaged a new generation of Australians who were drawn to stories of mateship, ingenuity and defiance of authority under adverse conditions. These attributes easily aligned with the Anzac legend. Weary Dunlop likely became Australia’s best known and much-revered war veteran.

Another key moment in the popular reflection on the Second World War took place in the mid-1990s. This was the year-long, nation-wide Australia Remembers 1945–1995 commemorative program marking the 50th anniversary of the end of the war. I was in high school; after the spark lit by my grandparents, this year of television documentaries, publications and events helped to confirm my enduring passion for the conflict.

Commemoration continued into the 2000s. In 2004, for example, the Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial was dedicated in Ballarat, Victoria. In 2011 the Bombing of Darwin Day (19 February) was made a national day of observance, first observed in 2012. Similarly, the Rabaul and Montevideo Maru Memorial was dedicated in Canberra at the Australian War Memorial in 2012. Veterans, family decendants and tourists have made regular pilgrimages and tours to the war’s battlefields and significant sites such as Hellfire Pass on the Burma–Thailand railway, the Kokoda Trail, and the Sandakan death march in Borneo. Even the public discourse surrounding the so-called “battle for Australia” in 1942–43, and the zombie myth of Japan’s plans to invade mainland Australia, contribute to popular interest. A catalogue search of the National Library of Australia for “World War, 1939–45, campaigns, Papua New Guinea”, for example, shows 150 books were published between 2000 and 2021. That was one new book published every seven-and-a-half weeks.

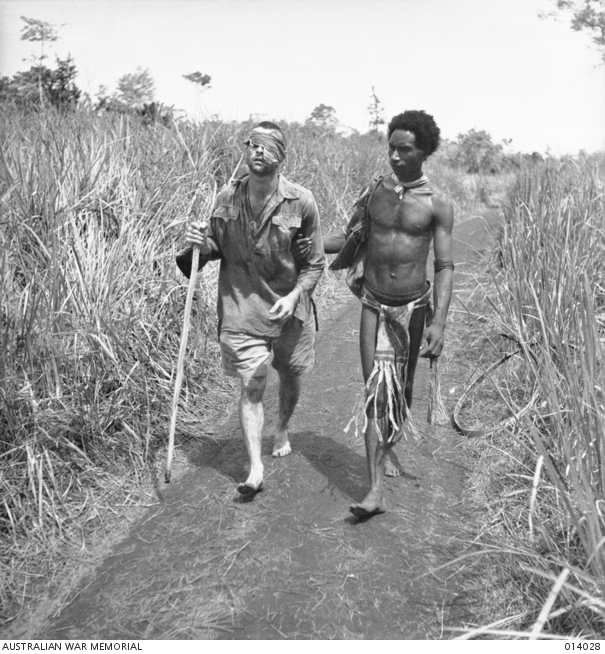

Raphael Oimbari leads Private George "Dick" Whittington through the kunai grass towards a field hospital at Dobodura, Papua. Photo: George Silk

Australian prisoners of the Japanese considered fit enough to work on the infamous Burma-Thailand railway, 1943. Photo: George Aspinall

What are we remembering?

Superficially at least, Australia’s Second World War appears to be well-remembered and commemorated. But it is worth asking what we are remembering. Is it only battles and campaigns that hold our interest, or is it about individual people, those who served and those who died? What types of events are commemorated: is it only dramatic or tragic moments? In 2012 the 70th anniversary of 1942 was marked with national commemorations and memorial dedications focused on the fall of Singapore, the sinking of the Montevideo Maru, and the campaigns in Papua. But in 2013, the 70th anniversary of the Allies’ New Guinea offensive, when Australian forces conducted their largest ever operations (see Wartime 64), went virtually unnoticed.

Perhaps a better question to ask is what are we not remembering? This, of course, is an open question. There is no shortage of significant issues yet to be adequately addressed, and new questions to be asked. These could include greater recognition of the civilian experience; the mobilisation for war work of Aboriginal communities in northern Australia; and the scientific and technical advances that saw significant achievements in all sectors, such as the battle against malaria and the development of aircraft production. We know about the presence of United States forces and personnel in Australia, but what about the British airmen posted to Darwin, or sailors with the British Pacific Fleet? The presence too of Dutch forces in Australia is nearly always overlooked. Race, sexuality, emotion: Australia’s experience of the war and the war years can be examined in many ways.

The Isurava Memorial, Papua New Guinea, 25 April 2012. Courtesy of Department of Defence. Photo: Nick Wiseman

From memory to identity or sentimentality?

Australia’s involvement in the Pacific War has been interpreted in terms of an independent Australia. One of the greatest champions of Kokoda was Prime Minister Paul Keating. Speaking in Port Moresby on Anzac Day 1992, he described the battles in Papua New Guinea as “the most important ever fought” by Australians.

The Australians who served here in Papua New Guinea fought and died, not in the defence of the old world, but the new world. Their world. They died in defence of Australia and the civilisation and values which had grown up there. That is why it might be said that, for Australians, the battles in Papua New Guinea were the most important ever fought.

The next day Keating flew to Kokoda, where he laid wreaths and kissed the ground. It was during the 1990s that Kokoda began to rise in prominence. As Hank Nelson argued, Kokoda’s appeal is its strong “Australianness”. The Kokoda campaign was fought on Australian territory, by Australian soldiers against the invading Japanese. Kokoda suited Keating’s push for an Australian republic. This is partly why Kokoda has replaced Tobruk, and why the Australian contribution to El Alamein is virtually ignored. Although vital to British and Commonwealth forces in the Middle East in 1941–42, those two actions are no longer easily recognisable as Australian.

Perhaps it is not what Australians did during the war that has endured; rather it is the values and attributes they are said to have displayed that have become significant. Speaking at the opening of Kachanburi War Cemetery in Thailand on Anzac Day in 1998, Prime Minister John Howard remarked that despite the terrible privations suffered by Australian prisoners of war, their mates bonded and motivated each other. Howard continued, “Mateship, courage and compassion, these are enduring qualities – the qualities of our nation. They are the essence of a nation’s past and a hope for its future.”

Les Cook, Anzac Day 2017. Photograph: David Whittaker AWM2017.4.213.55

This emotional and aspirational emphasis is best illustrated by the Isurava Memorial, dedicated in 2002 on one of the key battle sites of the Kokoda campaign. When the original battlefield cairn was installed at Kokoda in 1945, the text and dedication were simple. Kokoda was just one of many battles and actions fought in Papua and New Guinea. Sixty years later, at Isurava, the focus has become Courage, Endurance, Sacrifice and Mateship. These are said to be the qualities displayed by the Australians and Papuans along the Kokoda Trail. They are values that have become closely associated with Australia’s national identity. This is a theme repeated most recently by Governor-General David Hurley on Anzac Day 2022. Courage, mateship and sacrifice were part of the Anzac legacy, he said during his address to the nation. These characteristics are seen “in the service of our modern veterans and those still serving,” Hurley remarked. “The characteristics are not confined to our people in uniform. They are evident today in the actions of normal Australians.” They are seen during times of stress and emergency such as floods and bushfires.

Anzackery and Afghanistan

In the 21st century, the public focus of Australia’s war commemoration and remembrance returned to the First World War. The Centenary of the First World War in 2014–18 saw a tsunami of commemorative events around Australia and overseas. Many of those activities were naturally centred on the 100th anniversary of the Anzacs landing on Gallipoli. Over 120,000 people attended the Dawn Service at the Memorial in 2015, overflowing the grounds and filling Anzac Parade. Millions of dollars were spent on war commemoration. The Australian government’s Anzac Centenary funding to 2019 was approximately $342 million. Critics, however, protested against this spending and the celebration of so-called “Anzackery” – the perception of an excessive or misguided promotion of the Anzac legend.

Possibly in response to such criticisms, in recent years much of the public discussion has been to emphasise Australia’s “recent conflicts” in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. There has been a noticeable pivot from the public remembrance of historic conflicts to the welfare and wellbeing of living veterans and their families.

While historians are skilled at rediscovering lost stories and interpreting the significance of past events, we are notoriously poor at predicting the future. Will Australians continue to remember the Second World War after the last veterans have died? Those who lived through Australia’s war and fought in the Middle East, the Mediterranean, the Pacific and elsewhere are quietly passing away. In 2016 the Department of Veterans’ Affairs estimated more than 31,000 veterans were still alive. Since then around 5,000 veterans have died each year, as the table shows:

|

Surviving Veterans Year by Year |

||||

|

30 June 2016 |

30 June 2017 |

30 June 2018 |

30 June 2019 |

30 June 2020 |

|

31,700 |

25,000 |

19,300 |

14,600 |

10,800 |

Unfortunately, Covid-19 lockdowns, international and domestic travel restrictions, and limitations on public events during 2020–21 denied many veterans opportunities for public acknowledgement and reunions. The 75th anniversary in 2020 of the end of the Second World War in 1945 did not receive the attention it deserved. It is highly likely that the emphasis of public remembrance and the commemoration of Australia’s Second World War will continue to evolve into the future. The events and individuals of this past conflict will be reinterpreted through the lens of contemporary issues.

Described in the press as “one of the last remaining survivors” of the war, Les Cook was not concerned when he was asked by a journalist if he worried about the soldiers’ legacy being lost. He was amazed by young faces among the crowd. “The young people are showing so much interest in it. They don’t need any push to do so.” It is our responsibility to ensure that Australia does not forget.