Brothers: the story of Alec and Goldy Raws

How does a son tell a father whom they love that they're about to leave them, possibly forever? How does a father persuade a son not to leave, a son they have watched grow into a fine young man, a son they have nurtured and loved from the moment their boy opened his eyes, a son who they watched as he learnt to walk and now watched again as those same legs prepared to march him to war?

As John Alexander 'Alec' Raws sat there replying to his father's letter, he tried to explain how he had come to make the most important decision of his life:

I have received your letter this evening, just a few minutes after I have passed the medical test for enlistment. I propose to go into camp in a week or two, probably Wednesday week, or Monday week – today fortnight. In the meantime I shall study and drill.

If I had received your letter before, Father dear, it would have made no difference. And my decision has not been sudden. My mind has practically been made up for a month or so, before the recruiting boom to which you refer, but I was waiting to advise you immediately everything was fixed, and I was accepted. The reduction of the standard has enabled me to get through.

I must ask you not to worry, but rather to be proud that I your son am prepared to abandon all my comforts, all my life, all of everything, to fight for principles which I hold mean everything to the modern world, and, also, to look at it from another angle, apart altogether from patriotism, to go out to my friends and pals, to the other fellows of Australia, to my brother already there, to help them in a business of life and death in which they are hard pressed.

I do not think that I was ever a great man for heroics but I do believe that there are some things worth more than life. I curse the systems of government, the hideous fraud of civilisation, which permits this dreadful welter of blood and suffering to have enveloped the world in modern times. And yet I go to join in it, believing that the only hope for the salvation of the world is a speedy victory for the Allies. Holding such views, how can a man, judged to be physically fit for purpose, reasonably hold back? I think that, on looking at the facts in this light, you will agree with me.

I hope that you will be proud to think that you have two sons, who were never fighting men, who abhor the sight of blood and cruelty and suffering of any kind, but who yet are game to go out bravely to a war forced upon them. There are many men, wealthy and strong, who should have gone before me, and have not. But can that excuse me? Not for one moment.

I do not go because I am afraid that my friends may think me a coward if I stay, but I do feel that in going I am in my small way conferring upon you and dear Mother what should be not a crown of sorrow. You would not have your son, whatever else, a craven, one who would say that he thought others should go, but would hang back himself. If I prove unfit for service, well and good. But it has to be proved. I said before that I claimed no great patriotism. No government, other than the most utterly democratic, is worth fighting for. But there are principles, and there are women, and there are standards of decency, that are worth shedding one's blood for, surely. I am content to believe that you will be with me in this.

Death does not matter. If it comes through this agency early to me than it would have done otherwise, it can bring me nearer to you, my mother and father, you who after all I think are the only two people in the world that I have ever really loved. I would be glad to be out of it. The thing has been forced upon us. But it has to be faced. Do you not like to think that your many friends in England, so near to all the horror of the conflict, will be glad to think I am man enough to come over to them and help? There are many ways to look at it, and they all make it right.

You must not think that I writ hardly all about this, Father. I know that you will appreciate my motives. I do yours. Maybe you are right, but one has to settle such big questions as this in one's own soul. I am sorry that I was unable to see my way to ask for your advice, good and wise father that you have always been to me. I have made my own decisions for myself, since I left home as a boy, and this was one above all others that could be left to no one else. You and Mother should really be happy about it, now, shouldn't you?

And, after all, I might stay at home and be run over by a tramcar, you know.

I shall write to you again before I go into camp.

I must begin to practice sleeping on the floor tonight.

Letter from John Alexander Raws to his father, 12 July 1915

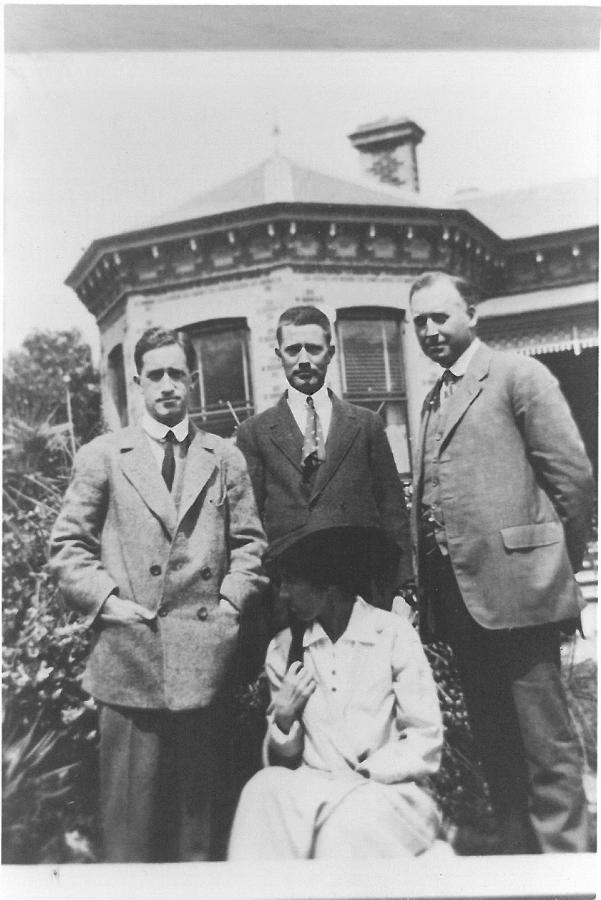

Alec and his younger brother Robert Goldthorpe Raws (nicknamed 'Goldy') had been born in Manchester in the United Kingdom. As young boys, they and their family had migrated to South Australia where the boys attended Way College and later Prince Alfred College. Alec had distinguished himself as quite the sportsman in his college years, in one instance scoring two centuries at an inter-college cricket match. He also captained both the cricket and tennis teams during his final year at the College. In the years after school the brothers had taken different paths. Goldy became a soft goods warehouseman based in Adelaide while Alec became a journalist. Alec had written for a variety of papers in South Australia and Western Australia before joining the Melbourne newspaper The Argus in 1907 where he became leader of the parliamentary reporting staff. During these years he continued to pursue sporting endeavours, winning several state tennis championships and representing Victoria several times in interstate matches. He also became a member of the City of Melbourne Rifle Club.

In August 1914, the First World War broke out and everything changed.

Group portrait of officers of the 23rd Battalion taken on board HMAT Euripides en route to Egypt. Goldy is in the third row, eighth from the left.

Goldy was the first of the two brothers to enlist, embarking from Melbourne on 10 May 1915. As one son steamed away from Australian shores, another was preparing to make the biggest decision of his life. Just over a month after Goldy left Australia, Alec enlisted. Their father had tried to stop a second son of his joining what was shaping up to be a horrendous war, but Alec had made up his mind and wrote to his father explaining his motives. On 29 March 1916, nearly a year after his brother, Alec left his adopted homeland for what would be the last time.

In the time since, Goldy had served at Gallipoli and been promoted to the rank of lieutenant. His unit, the 23rd Infantry Battalion, had been involved in manning one of the most trying parts of the Anzac front line at Lone Pine. In December, Goldy along with the rest of the Australians had been evacuated from Gallipoli. In March the following year (1916), as his brother Alec was preparing to leave Australia, Goldy and his battalion had been transferred to the Western Front in France. It was now July 1916 and Alec was on his way to be reunited with his brother for the first time since Goldy had left Australia.

It was a reunion never to be.

On 23 July 1916 the Australians were ordered to capture Pozières, a small village in the Somme valley in France. Over the next two weeks, in some of the most bitter and costly fighting of the war, the Australians would struggle to capture and hold the village in the face of fierce German counter attacks and artillery bombardments. Goldy's unit, the 23rd Battalion, would be one of several to participate in the fighting to come.

From a tracing by 10347 Staff Sergeant Arthur Edward Scammell; map of Pozieres and Mouquet Farm area.

Looking south towards Pozieres, this position was the scene of severe trench warfare, neither side holding it for more than a few hours at a time. It eventually became, in that particular period of fighting, part of no man's land.

On 28 July 1916, Goldy failed to report back. The chaotic nature of the fighting on the Western Front meant that soldiers were often classed as missing if they did not return. There was a possibility that they had been captured as a prisoner of war, but the most likely outcome was that they had been killed and had become one of the several hundred thousand men from both sides in the First World War whose bodies would never be located and/or recovered. Alec arrived on the Western Front and joined Goldy's battalion the day after his brother was listed as 'Missing In Action'.

He had narrowly missed seeing his brother one last time.

Alec himself was quickly drawn into the fighting and penned a letter detailing the fighting:

One feels on a battlefield such as this that one can never survive, or that if the body lives the brain must go forever. For the horrors one sees and the never-ending shock of the shells is more than can be borne. Hell must be a home to it. The Gallipoli veterans here say that the peninsula was a happy picnic to this push. You've read of Verdun – they say this knocks it hollow. My battalion has been in it for eight days, and one-third of it is left – all shattered at that. And they're sticking it still, incomparable heroes all. We are lousy, stinking, ragged, unshaven, sleepless. Even when we're back a bit we can't sleep for our own guns. I have one puttee, a dead man's helmet, another dead man's gas protector, a dead man's bayonet. My tunic is rotten with other men's blood and partly splattered with a comrade's brains. It is horrible, but why should you people at home not know? Several of my friends are raving mad. I met three officers out in No Man's Land the other night, all rambling and mad. Poor Devils!

Myself, I am all right. I have had much luck and kept my nerve so far. The awful difficulty is to keep it. The bravest of all often lose it. Courage does not count here. It is all nerve. Once that goes one becomes a gibbering maniac. The noise of our own guns, the enemy's shells, and getting lost in the darkness. You see this is enemy country. We're in the remnants of their trenches and wrecked villages, and the great horror of many of us is the fear of being lost with troops at night on the battlefield. We do all our fighting and moving at night and the confusion of passing through a barrage of enemy shells in the dark is pretty appalling. You've read of the wrecked villages. Well some of these about here are not wrecked. They are utterly destroyed so that there are not even skeletons of buildings left – nothing but a churned mass of debris, with bricks, stones, and girders and bodies pounded to nothing. And forests! There are not even tree trunks left, not a leaf or a twig. All is buried and churned up again and buried again.

The sad part is that one can see no end of this. If we live tonight we have to go through tomorrow night and next week and next month. Poor wounded devils you meet on the stretchers are laughing with glee. One can not blame them. They are getting out of this.

Letter from John Alexander Raws to Norman Bayles M.L.A., 4 August 1916

An Australian fatigue party from the 7th Brigade (far left) carrying piles of empty sandbags to the front line through the devastated area near Pozieres. This picture was taken on 28 July 1916, the day that Goldy would be killed in action.

Alec was initially hopeful that Goldy might be located. Perhaps he had been captured by the Germans and was now a prisoner of war? Perhaps he was lying wounded in a field hospital behind the line somewhere? While a Court of Inquiry was convened two weeks after Goldy's disappearance to determine what had happened to him, the fighting shifted to an area near Pozières known as Mouquet Farm. The inquiry determined that there was insufficient evidence to conclude his fate and so he remained listed as missing. However, it had now been several weeks since Goldy had gone missing and Alec had lost all hope that his brother might still be alive.

In a letter to his brother at home on 19 August he wrote:

Before going into this next affair at the same dreadful spot, I want to tell you, so that it may be on record, that I honestly believe Goldy and many other officers were murdered on that night you know of, through the incompetence, callousness, and personal vanity of those high in authority. I realise the seriousness of what I say, but I am so bitter, and the facts are so palpable, that it must be said.

Please be very discreet with this letter – unless I should go under.

Letter from John Alexander 'Alex' Raws to his brother, 19 August 1916

The Villers–Bretonneux Military Cemetery with the Cross of Sacrifice and the Australian National War Memorial beyond. [DVA].

This would be his last letter.

On 23 August, shortly after entering the firing line for a second time, Alec was killed by a shell along with several other soldiers nearby. The news of his death reached his parents in Australia on the day of his birthday. At this time Goldy was still listed as missing, but by then his family knew that he had more than likely been killed. The news of Goldy's probable death reached his parents in Australia on the day of their wedding anniversary. However, it would be over a year later that he would be officially reported as having been killed in action. Through the use of several eyewitness testimonies it was eventually concluded that he had been killed on 28 July, the same day he had been reported missing, likely when he and several others were involved in trench digging in no man's land at Pozières.

It is estimated that their battalion lost 90 per cent of its original members in the fighting around Pozieres and Mouquet Farm in July and August 1916. In just over a month of fighting the Australians had suffered over 20,000 casualties.

Alec was 33 years old and his brother Goldy was 30 years old. Their final resting places could not be located and so both brothers are commemorated at the memorial to the missing at Villers-Bretonneux Memorial in France.

Goldy and Alec wrote many letters to their family and friends at home while serving abroad in the First World War, a few of which have been mentioned in this article. The transcripts of their entire collection of letters have been digitised as part of the Anzac Connections digitisation project and are available to read online here:

View the letters of Alec and Goldy Raws

Letters such as these are invaluable. For a soldier at the front, the act of writing home was often a cathartic one. They would put into words, or at least try to, the often inexplicable horror and suffering of the war. In a war where the fighting was often chaotic and relentless, finding a moment to put these words down on paper was often the first opportunity a soldier had to process what had happened. It was an opportunity to try and make some sense or meaning out of the unfathomable. Letters were also a connection to home, to family and to the life they once knew. Into these letters Australian soldiers poured their most intimate thoughts, loves and fears. For many of them it would be their legacy and final record. The Australian War Memorial is the custodian of a great many private collections from the First World War. They are as precious to us here at the Memorial as they were to those who wrote them so very long ago.

The brothers also feature in Episode 3: Weapons of Mass Destruction of the History Channel documentary The Memorial: Beyond the Anzac Legend.