'We were part of recording history'

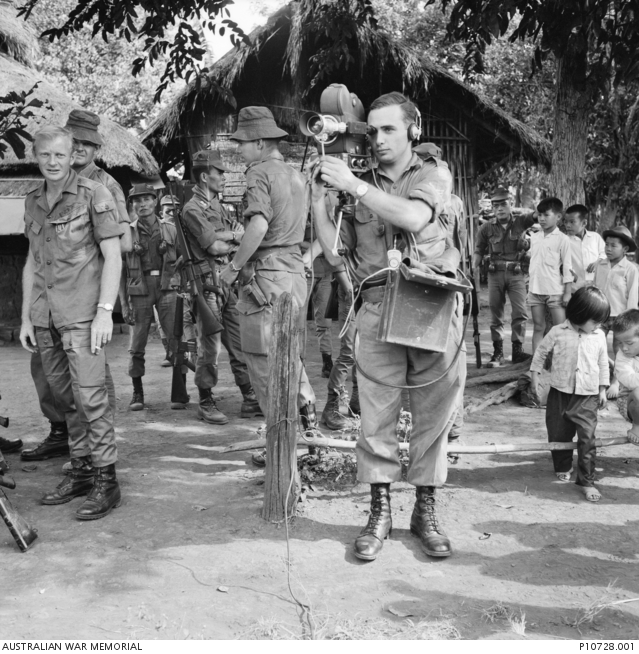

Sergeant David Combe, official Army Public Relations cinematographer, documenting Christmas messages from Australian soldiers serving in Vietnam.

It was the early hours of the morning in Phuoc Tuy province, Vietnam.

David Combe was on watch and the slightest sound seemed amplified. The army photographer had gone out with a patrol on the Saigon River to capture images and footage for news agencies in Australia when the boat he was in capsized, leaving the group stranded with little to no food or ammunition.

“We were going up the river, late in the day, against the tide, and I was in the last boat,” David said.

“We were pretty heavily laden – machine-gun, radio, rifles – and we struck a bow wave and got swamped and turned over.

“Not all the heads popped up above the water, so myself and one or two of the others whose heads did pop above the water, groped around in the muddy waters and found a couple of guys who were trapped under the boat and pulled them out.

“The boats ahead of us, realised we were missing, came back, and said, ‘We’ll go ahead, do what we have to do, and set up an ambush for the night. You guys, stay here, push your boat into the mangroves, and set yourselves up.’

South Vietnam, April 1969: David dons his gas mask before entering a tunnel found in a Viet Cong camp during Operation Surfside.

“We had one machine gun, with most of the ammunition missing, but all our rations, and the radio, were all at the bottom of the Saigon River

“We had just one belt of ammunition, instead of three or four... But you didn’t sleep. The mosquitoes. And the slightest croaking of a frog, you thought was a Viet Cong somewhere.

“Then at two o’clock in the morning, this bloke I was on [watch] with said, ‘Hey Sarge, do you want some of this,’ and he pulled out a little hippy [or hip flask] of Bundaberg rum to keep us warm.

“The next morning it was low tide, so we found the radio, found the machine-gun ammunition, found the rations. When the main patrol came back, and we got back to [the Australian Task Force base at] Nui Dat, we rinsed all the gear in fresh water, and then sent it to Saigon that night to hand it all in to RAEME [Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers] with a lost and damaged report.

“And that was the trouble in Vietnam... Just trying to keep the cameras operating was bad enough.

“We were always sending our gear off to the electrical and mechanical engineers in Saigon to be sent back to Australia to be repaired, and that was my biggest repair job, when the cine camera, both still cameras, and my light metre, all went for a swim in the Saigon River.”

David was awarded the Ilford 1969 Photographic Award for the Army's 'Picture of the Year' for this image of Private Bob Hunter and his tracker dog Milo. Photo: David Combe

The 22-year-old from country New South Wales was an official Australian Army Public Relations Photographer in Vietnam from November 1968 to November 1969. He had been called up in the 1966 National Service ballot, but his service was deferred so he could finish his journalism cadetship.

His great uncle, Cassimir Combe, had been wounded on Gallipoli during the First World War and had died at a field hospital in Egypt. His mother worked in the army records office at the Sydney Showgrounds during the Second World War while his father served as an aircraft mechanic in the Royal Australian Air Force in New Guinea. David never dreamt he too would go to war.

As a boy growing up in Forbes, he was more interested in journalism and photography.

“While all the jocks were playing sport in school, I’d hide in the library and edit the school newspaper, which was printed at the local newspaper,” he said with a laugh.

“I was the nerd of the class … and it got me out of sport. But I was also really interested in the electronics of radio and television so I thought about becoming a television broadcast engineer ...

“Then when I left school, I was working as a jackaroo, waiting for the results to come out, not really knowing what I was going to do in the New Year, and the editor of the local newspaper, the Forbes Advocate, knocked on my family’s door and asked my father if I’d like to start a cadetship in journalism.”

David, right, being presented with the Ilford 1969 Photographic Award for the Army's 'Picture of the Year' by the Commander of the 1st Australian Task Force, Brigadier C. M. I. Pearson.

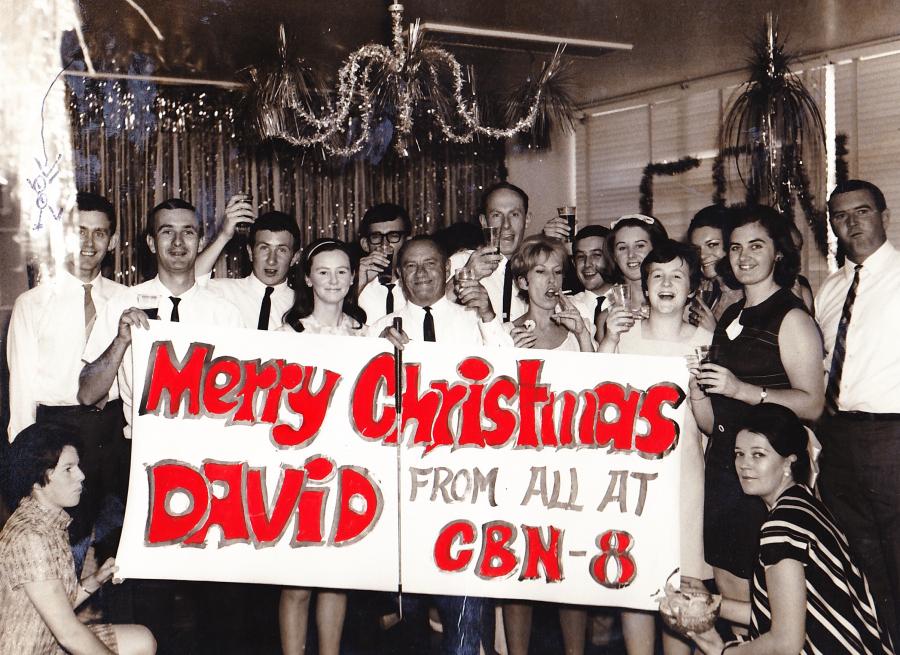

He taught himself how to use a cine camera and went on to complete his cadetship at Channel 8 television in Orange.

“That was when I got called up,” he said. “It was like being told you have cancer. And I know what that’s like. You’re a bit shocked. “It comes in a letter, in an ominous brown envelope, and we all knew what it looked like, because we’d seen pictures of draft dodgers burning them.

“Then you were sent for a medical exam at the local government appointed GP It was all very basic – I don’t know if it told the army anything – and then you waited for your call up ...”

After training at Kapooka, David was posted to Australian Army Public Relations in Canberra. He was sent to Vietnam less than three months after completing his trade testing, battle efficiency and jungle training.

“You had to report to the army movement office in Sydney, and then they herded us onto buses to go out to this depot out towards the airport," he said. "The Save Our Sons ladies were out there in full force at the front gate, poking their protest banners at us, so we felt much safer once we got inside. We didn’t think Vietnam could pose nearly as big a threat as the SOS ladies.”

His first job was to photograph a warrant officer who had been going to work at the Free World Forces Headquarters in Saigon when a motorcyclist hooked a satchel bomb on to the side of his bus. It was the first of hundreds of images David captured during his year in Vietnam.

Saigon, South Vietnam, November 1968. Warrant Officer Class 2, Don Andrews, examining a satchel bomb, which was hooked to the side of a bus alongside the seat he was in. David took this image on his first day in Vietnam. It was the first of hundreds of images he would take in Vietnam. Photo: David Combe

“It was frightening at times,” David said. “But you knew it was a war zone.

“Flying between Saigon and Nui Dat, the whole landscape was pock marked with bomb craters, usually full of water from the rain. They were glistening in the sun so the place was sort of bejewelled with the glistening of these bomb craters.”

He had followed the war in the media and was surprised to find the situation on the ground was not as he expected.

“Once there, I saw the posting to PR [public relations] as an opportunity to redress misconceptions about the war, but I would have been equally happy to count blankets in a Q [Quartermaster] store somewhere,” he said.

“I knew what was being portrayed by the media wasn’t what was actually happening. We weren’t ‘baby killers’. These guys were working hard, slogging their guts out for the country, and yet they were copping all this crap at home, so I thought if I could help alleviate that in any way and show what was really happening ... then that was my mission.

“I couldn’t have worked with nicer people …

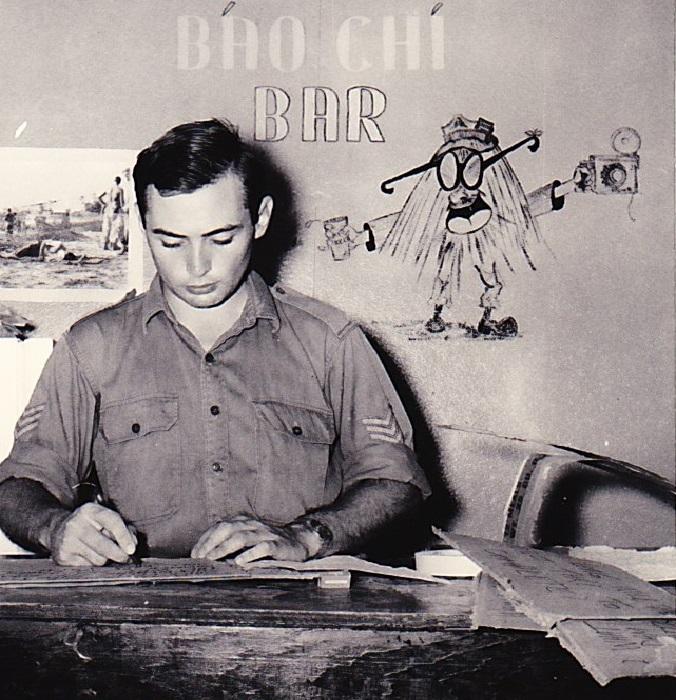

David "balancing the books" in the Bao Chi Bar (Press Bar) at the Nui Dat Press Centre. Photo: Courtesy David Combe

The staff at CBN Channel 8 in Orange, NSW, sent David a Christmas message while he was serving in Vietnam. Photo: Courtesy David Combe

“You built up a circle of trust with the units. And they understood our mission was to make sure they were not forgotten at home. Even the SAS allowed us access, and there was no pixilation of faces back then.

“The ‘Homeboys’, as we called them, were the soldiers whose photos we would take for their local newspapers at home. They were our bread and butter, and so we were always welcomed in to the units in the hope they would get their pics in the paper.

“You made a really good connection with the guys, and they loved hamming it up for the camera... They were the real soldiers ...

“I just regret that we were unable to provide them with prints [of their photographs]. We rarely received them back from Canberra.

“We were more likely to see our pics in a newspaper left in the mess or in a clipping sent by our parents with a note, ‘Is this one of yours?’

“But the homeboys live on today in unit magazines, histories and family scrapbooks.

“The thing that I didn’t like, and never have liked, and never will like, is handling weapons.”

South Vietnam,October 1969. Members of D Company, 5th Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (5RAR), cool off in a jungle stream and fill their water bottles. The soldier on the right keeps a watchful eye open for signs of the enemy. Photo: David Combe

More comfortable armed with his cameras and a notebook, David would record stories, film and photographs for everything from the army newspaper to major news outlets, as well as undertaking special requests for magazines such as TV Week, Australian Women’s Weekly and Australian Dog World.

“The first operation, I remember I was really scared. I didn’t know what was going to happen, where it was going to happen – in front of me, behind me, next to me, under me – but I was quite lucky.

“When I turned up at the battalions that knew me, or the companies that knew me, they’d say, ‘Oh come with us Sergeant Combe, nothing ever happens when you’re with us.”

He remembers hearing about the battle of Binh Ba in June 1969 and seeing villagers fleeing from the fighting.

“Someone came down to the press centre, and I was told, ‘Get down to the main gate ... there’s all these people.’

“It was like a refugee scene from the Second World War. All these men, women and children were just streaming down.

“I went up [to Binh Ba] the next day and the place was just a ruin. There were still bodies being pulled out of collapsed bunkers and women had come back into the village and were picking up the dead chooks, plucking them and boiling them ...

“And then the civil affairs people started fixing up the houses and putting tin roofs on what had been beautiful little French houses with terracotta tiles.”

Hoa Long, South Vietnam, March1969: Private D. Smith guards a Vietnamese bread vendor. Photo: David Combe

South Vietnam, August 1969: A Viet Cong (VC) who surrendered after an ambush is escorted to an awaiting RAAF helicopter by two troopers. Photo: David Combe

South Vietnam, March 1969: A soldier writing a letter in the jungle. Photo: David Combe

Two months later, David filmed the dedication of the Long Tan Cross.

“It was very emotional and very, very moving,” he said. “We moved out on foot from Nui Dat and when we got there, there was a certain eeriness about the rubber plantation because there was still a lot of unexploded and exploded ordnance in the area …

“It was 18 August 1969, three years to the day after the battle of Long Tan. The engineers had produced a nine-foot high reinforced concrete cross to commemorate the battle, and it was set down by Iroquois helicopter on what had been the centre of 11 Platoon’s position during the battle...

“Members of the 6th Battalion, on their second tour of duty, had come in the night before to secure the area and to prepare a clearing for the cross to be erected ...

“All in all, it was one of the most moving experiences of my 12 months in Vietnam.”

South Vietnam, March 1969: Corporal B. Dunn, rifle at the ready, moves through the bush while on patrol. Photo: David Combe

Phuoc Tuy Province, South Vietnam, January 1969: Private Wally Fiedler, left, and Private Ken Winkley, of the 1st Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR). 1 RAR was conducting a cordon and search of Phu My village. Photo: David Combe

April 1969: The armoured personnel carrier detonated a mine on operations against the Viet Cong in Phuoc Tuy Province. Sergeant Craig Haydock, left, and Sergeant Peter Edwards, check the damage. Photo: David Combe

Today, David’s collection of official photographs and cinefilm are part of the National Collection at the Australian War Memorial.

“I’m very proud it’s here at the Memorial forever,” he said.

“When I came back from Vietnam, and for years and years afterwards, nobody ever asked me what it was like, except my father. None of my brothers. None of my work colleagues. None of my friends. People just erased it from their memory.

“It was very hard [coming home] and I was very angry that nobody showed any interest.

“The first reunion I went to was the Welcome Home Parade in ’87... and I was surprised to see how old we all were. It was recognition at last. And it was just amazing ...

“As the community’s long-term memory of Vietnam fades, it’s gratifying to know some fragments of what it was like there will remain for the pubic to view and for academics to study at the Memorial.

“I never knew where it was all going to end up. I just hoped that it would be archived somewhere ... so that it would be accessible decades and hopefully centuries later ...

“We were part of recording history, and that’s pretty valuable ...

“It makes people aware of the horrors of war.”

David Combe features in the Memorial's new touring exhibition ACTION! Film & War. The exhibition follows the stories of Australians armed with cameras who have shared their experiences as they record history and bear witness to conflict – either as a professional duty or for their personal record. Drawing chiefly on the Memorial's collection, it shares stories of Australia, war and the power of the moving image. ACTION! Film & War opens at the State Library of New South Wales on 6 October 2023. For more information about the exhbition, visit here.