Hiding in plain sight

Megan Spencer

My heart stops. There he is.

At the end of another endless click of the mouse – it’s him. Harry. My grandfather. Hiding in plain sight on the Australian War Memorial website.

“I found you,” I say out loud.

P03138.005. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C388100

Within the oceanic collection of media, records and stories of those who’ve served for “King and country”, “Queen and country” or simply “country”, it’s him. Just like he said in his meticulously handwritten, stream-of-consciousness memoir.

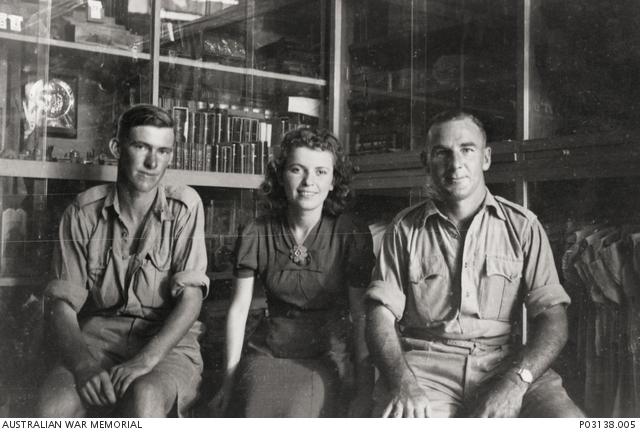

Recently embarked from the ports of Melbourne to those of the Middle East, he’s in situ in 1940: on leave, awaiting orders and for “the show” to begin. Best mate Eric Eldridge is perched to his right. In the middle is “shop lady” ‘Miss B. Kornblit’. All posing for a souvenir snap in a “curio shop” in Tel-Aviv.

Somehow one of Harry’s Second World War photos has surfaced in the collection. I don’t know how it got there but I’m so happy to see it. Finally I found the right keystroke to fish it out.

The servicemen are fit and fresh, sporting the reticent half-smiles of soldier–tourists unaccustomed to travel. They seem so alive in this picture. It’s as if they’re here, now, blinking back at me.

It’s a telling moment – a “before” picture, taken prior to the ravages of battle, privation and hardship. They’re yet to see action, yet to become prisoners of war. I know the tragedy of what’s next.

Tears spring forth. I can’t see the screen.

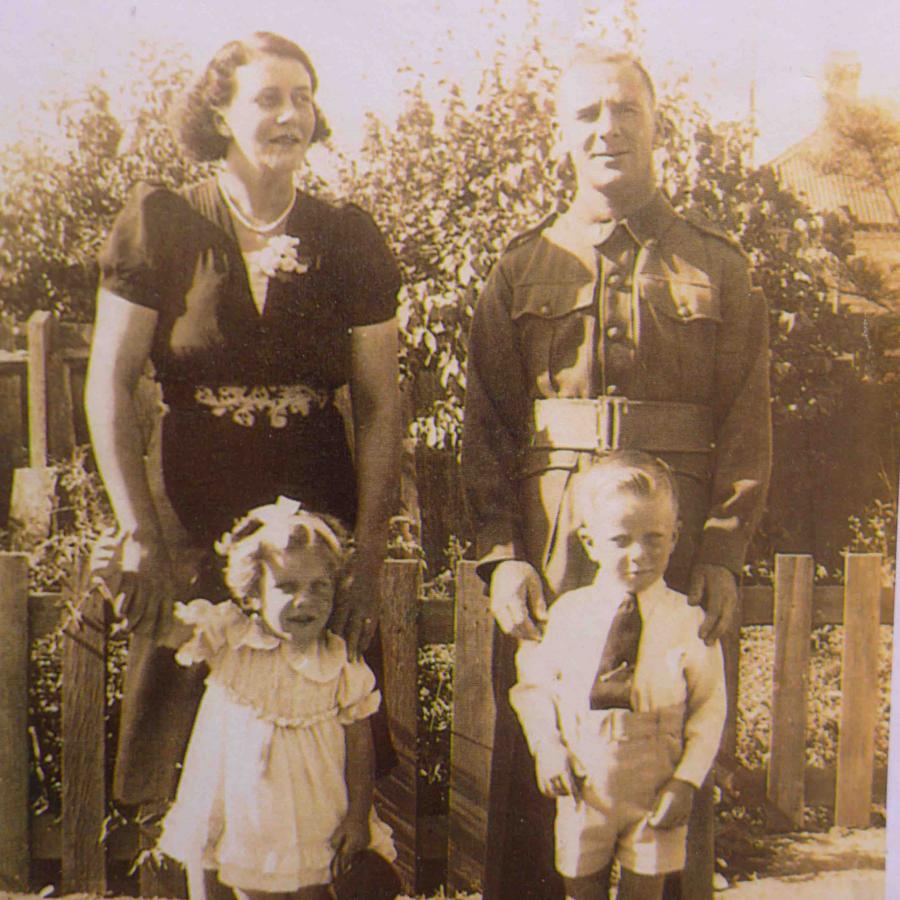

Just before Harry left with the 6th Division for the Middle East: Megan's grandparents Lillian and Harry with their children Margaret and "Bobbie" in 1940.

Corporal Henry James Bailey Spencer, VX1113, was a “39-er”, one of the original volunteers who enlisted in the Second AIF to fight against Hitler’s relentless German army during the Second World War.

The last survivor of 13 children – ten boys and three girls born between 1897 and 1917 – “Harry” was born in 1910 and died in 1987. He was also one of the five Bailey Spencer brothers who served in the ADF: Richard (aka “Charles”) in the First World War; William, Harry and Nathaniel in the Second World War, and Richard’s twin Hugh serving in both world wars.

Assigned to the 2/7th Australian Infantry Battalion, part of the second formation of the Anzacs in Greece, Harry fought in the battle of Crete. In the rear guard left on the island during this ill-fated, sacrificial campaign, on 1 June 1941, along with Nathaniel and thousands of other Australian soldiers, he was captured by the German army.

Instantly – from a whisper to a bang! – Harry went from Allied soldier to prisoner of war, spending the next four years (1941–1945) in as many prison camps. Waiting at home, not knowing whether they’d ever see him again, were Harry’s wife Lillian (my grandmother) and their two small children, Margaret and “Bobbie” (my father).

Recovered during a forced march, Harry survived the ordeal and returned to Australia. But as his epic memoir reveals, becoming a prisoner changed the shape of his war – and life – forever, creating intergenerational ripple effects still felt to this day.

Coming from poverty, poor health and a huge family, you might consider Harry a hard man before he left for war. When he returned home, in many ways he was even harder. Like so many solders of the time, he rarely spoke of what happened. And like so many prisoners of war of that time, he was effectively silenced.

Official group POW photo sent home to Harry's wife Lillian in 1941, from Stalag VII/A, Moosburg. (Harry is pictured back row, extreme right, without cap). https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C388121

As a younger person I wasn’t particularly interested in Harry’s war story.

I don’t really recall him being grandfatherly towards us kids. He seemed to be difficult, always fighting with someone. I never understood why.

But at 52 years of age, that’s all changed. My heart aches with compassion for him. Empathy has brought understanding. Love.

Having recently lived in what was the country of his internment, Germany, something stirred. Watching at close range the re-emergence of extremist views in Europe – the kind that led to the conflict in which he’d fought 70 years earlier – I kept thinking about him, wondering what he went through.

On a visit home to Australia, at a family reunion listening to my kin talk about the war experiences of our ancestors, I also realised just how present the war still is for my family – both world wars. How had it taken me this long to notice?

On return to Berlin where I’d be living for another nine months, I decided to embark on a journey of historical empathy: to walk a mile in Harry’s shoes and visit the sites of his suffering.

To start with his story and see where it lead me.

Photo: Robert Spencer © 1987

Harry’s story may not seem that remarkable. It’s similar to that of the thousands of other men and women who’ve served in wars for Australia.

Coming to know Harry as I have these past 18 months, my feeling is he probably didn’t think he mattered much in the scheme of things – perhaps only during his time in the army.

That picture I unearthed serves as a kind of visual honour roll to his wartime experience. It makes his story not only real but unique. And anyone can see it.

Acknowledgement is a powerful thing.

It means he’s not just another soldier lost to time and the big over-arching one-size-fits-all nation-building narratives that often eclipse military history. It’s proof that he was not only there, but that he went through something terrible and transformational.

That his personal soldier story counts. That it’s part of something much bigger, inter-connected and vulnerable – a giant mosaic of human stories that beggar belief. Manifesting alongside the thousands of others in the archive, there are no ‘small’ stories here, only big. He’s etched into the bedrock of the second, centurial, violent global conflict to re-shape humanity.

I never doubted it for a second. But its presence gives voice to that experience.

When I began the journey of looking into my grandfather’s war service, I became overwhelmed with the urge to give his story voice too. To listen, learn. I’d finally come to realise that the great tragedy would be to forget what Harry went through. What the world went through. What many still go though.

I decided to make a podcast about it.

It’s been a long journey so far, demanding and illuminating. With Harry as my guide, the project has taken me across land and sea, two world wars, three generations, and a century worth of unsettling history and precarious memory.

With ears wide open I’ve recorded and listened to historians, authors, battlefield guides, serving members, custodians of culture, relatives, war field pilgrims, and civilians who, like me, are seeking traces of their own kin.

I’ve also found myself asking some big questions around our time-honoured tradition of remembrance and the intentions behind it. In our volatile post-truth era of alternative facts, siloed discussions and digital pile-ons, might we be forgetting the lessons of history? Are we still listening to the past, to the stories of those who lived through such terrible times?

Can remembrance help keep the peace?

As the sun goes down on the Centenary of the Armistice, 100 years since “the war to end war” and the start of a peacetime many thought would remain, perhaps it’s timely to contemplate – as they did in 1919 – what peace means. To consciously try to “understand war” and “take war seriously” as historian Margaret MacMillan urged audiences last year.

To investigate our practice of remembrance and its role in society, as a way to honour what our Harrys went through: what they gave up and gave us in order to create the peaceful future many of us now enjoy?

So that we not only never forget but we also continue to actively remember well for the generations to come.

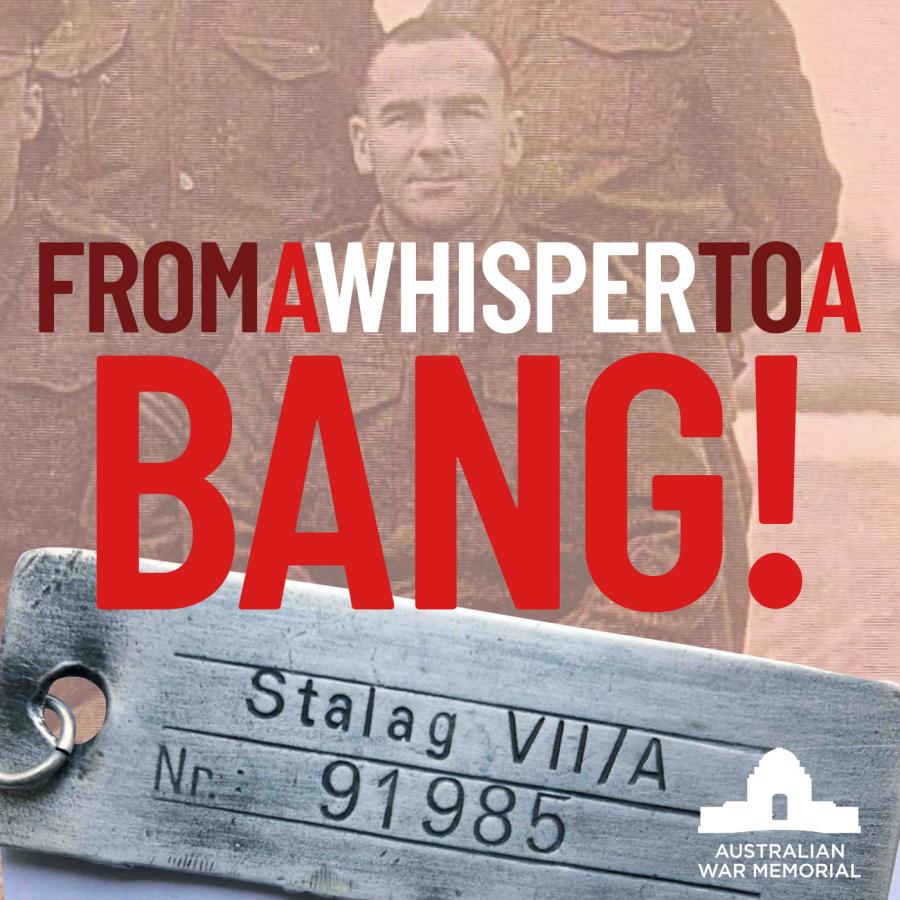

From a whisper to a bang! is a podcast series about remembrance, an Australian prisoner of war in Second World War Germany and an emotional journey in historical empathy, presented by Australian broadcaster Megan Spencer for the Australian War Memorial.