‘He is always in my heart’

Studio portrait of Merle Kelway Hare who served in the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service during the Second World War.

Merle Hare was in a daze.

It was early March 1945, and her twin brother, Sergeant Donald Kelway Storrie, was missing, presumed dead. His plane had disappeared while laying mines in the South China Sea and she would never hear from him again.

“It’s the worst thing that has happened to me in my life,” Merle said.

“I was in the Navy then, so Dad rang the Navy, and that was how I found out. I was called to the office… They presumed his plane had been shot down somewhere … I was absolutely swamped; I suppose it’s what they call shock.

“I just lay in my bed the whole night, looking out the window. I was absolutely floored, but being in the position you’re in, being in the Navy, you still had to get up, and you still had to go and do everything.”

Twins Merle and Don Storrie. Photo courtesy of Merle Hare.

Don (back row, far right) and the crew of No 20 Squadron, RAAF, Consolidated Catalina A24-203 which failed to return from a mission to the Pescadores Islands on the night of 7 March 1945.

A fitter and turner by trade, Merle’s brother Don had enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force in November 1940 and was a flight engineer on a Catalina flying boat when it disappeared during an operational mission on 7 March 1945.

“It was awful,” Merle said.

“The chief gave me three weeks leave to go home to my parents.

“But I was not sleeping or anything, and one of the girls said to me one night: ‘Merle, sit up and look at me. Your brother is gone. You must realise that now. Nobody knows what’s happened. You’ve got to face it, and come out and be yourself again.’

“She pulled me out of it really, because I was just walking around in a daze, and doing the work that I had to do.

“You were in the war … Things were happening to everyone else. And then it happened to you … Everybody was losing someone.”

Don enlisted on 29 November 1940 as an engineer and was stationed at Laverton, Point Cook and Wagga.

More than 75 years later, Merle, now 100, still misses him every day.

“After all these years, there might not be tears, but he is always in my heart, and I always think about him,” she said.

“He was a lovely man with blue eyes and blond hair, and if there was ever anything I needed, he was always there to help.

“I’ve got a big photo of him here … I call it my gallery … and that is him perfectly.

“He was lovely – quiet, intelligent, and a very good engineer.

“I was the one darting around, doing things all the time, and he was always behind me.

“He used to call me ‘kid’ because I was the last one out and he was older.

“But we were always together, and we never ever had an argument.”

“It was very special,” Merle said. “It’s never ever left me, and here I am; I’ve lived 100 years, and Don only had 25.”

Merle marked her 100th birthday by laying a wreath in his honour at a special Last Post Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. It was attended by the Chief of Air Force and the Chief of Navy.

“It was very special,” Merle said. “It’s never ever left me, and here I am; I’ve lived 100 years, and Don only had 25.”

Surrounded by friends and family at the Last Post Ceremony. 20 January 2020.

Vice Admiral Noonan presented Merle with a gold medallion and flowers to mark her birthday. 20 January 2020.

The Last Post Ceremony was on Merle and Don's 100th birthday.

Merle and her twin brother Don were born in Elsternwick, Victoria, on 20 January 1920 to Sydney and Myrtle Storrie, of Sassafras. They grew up in the Dandenong Ranges with their older sister Alva, “right amongst the wattle and ferns”. The family home, Monreale, had been built by their father, a marine engineer, and was run as holiday accommodation by their mother.

Merle’s brother Don was completing his apprenticeship with John Sharp and Son in South Melbourne when the Second World War broke out in 1939.

“It was the 3rd of September and we’d been out playing tennis,” Merle said. “I was working at Myers in the city, and I used to spend my weekend back home at Sassafras, doing my ironing and washing and getting ready to go back to work, but Don said there’s more to life than work, and he made me go to tennis with him, and that was on the Sunday afternoon.

“We came back to Monreale … and it was about nine o’clock at night. We’d had our meal, and we were sitting there in the lounge room – a big, beautiful lounge room with a great big fire, bluestone chimney, and balcony. We were looking at great gum trees right over the valley, and a lovely creek bubbling, with tree ferns and everything. It was just beautiful, and then the Prime Minister came on the radio and made that statement. ‘People of Australia… The news has just come through … Germany has invaded Poland … England has gone to help the Polish people, and therefore we are at war with Germany.’ I remember that clearly … and I’ve recited that many times.

“[Our friends] Jack Millard and Fred Bye jumped to their feet and went and joined up immediately … Fred Bye was five days older than us, and Jack Millard was about a year older, and they just skedaddled off straight away … and I never saw them again until they came back.

“There was no conscription then, and everybody … all our school mates, all the young men … they all joined up straight away in a great rush … whereas Don had to finish his apprenticeship. Apprentices were not allowed to join up to go overseas during the war, and Don had another 12 months to go.

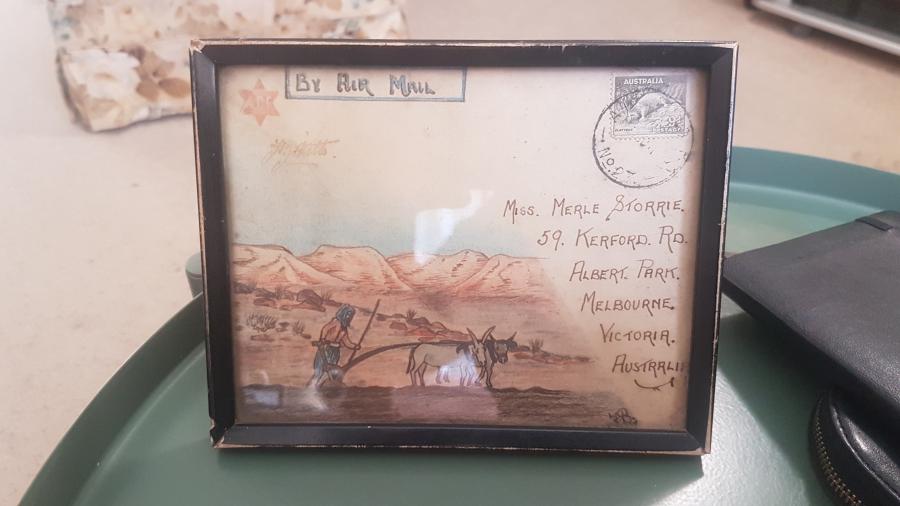

A letter to Merle sent by Jack and Fred. Photo courtesy of Merle Hare.

Don enlisted in the Air Force within months of completing his apprenticeship in 1940. He served at 2 Service Flying Training School in Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, and had a brief spell back in Melbourne before being sent to the Northern Territory in April 1942, serving at Darwin, Pell, Batchelor, and Birdum. He returned to Melbourne in April 1943, and was posted to No. 1 Aircraft Depot at Laverton. He returned to Wagga Wagga that same year to marry his sweetheart, Alma Crichton, on 11 September. Merle was one of the bridesmaids.

Merle in her Navy uniform. Photo courtesy of Merle Hare.

She had enlisted in the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service in March 1943, and their older sister Alva had joined the Australian Army Nursing Service in 1941.

“I loved every minute of my time in the Navy, and I was very happy to join it,” Merle said.

“I was working in Myers in the city in the salaries office … and this old dear was in charge of the staff. When she heard that I was going to go into the Air Force like my brother, she called me into her office.

“She said the Navy had decided they would select women to take the shore positions so the men could go out to sea on the ships, and she sent me to the naval office.

“There were only about 100 of us in the first intake, and we had to wait until they built our huts, as we called them. We were going to the Flinders Naval Depot and each one of us had to have our uniforms tailor made because they had nothing for women.

“I used to work in the office, the salaries office, and I costed all the feeding of anything up to 3,000 men. You had your job and it didn’t matter what you were, you did your job and that was it.

Don and Merle's older sister Alva joined the Australian Army Nursing Service in 1941.

“When I took my request [for leave to go to my brother’s wedding] to the head lady, she ripped the request up, tore it in half, and said: ‘Don’t you know there’s a war on?’ I stood to attention in front of her, and I said, ‘Madam, I wouldn’t be here if there wasn’t a war on.’

“She didn’t have an answer for that and I went back and I told the chief what had happened. He jumped to his feet … and I got leave to go to my brother’s wedding… and I always remember this.

“No one was allowed to travel anywhere – they’d stopped people travelling unless it was personnel for the Army, Navy or Air Force – but I managed to go.

“I had got my ticket through the Navy, and they wouldn’t let me on the train. Don said, ‘You can have my seat,’ but I said, ‘Don, you can’t get married without you,’ and he said, ‘Don’t you worry about that; I want you on the train now.’

“I had been moving all day from queue to queue to try and get a seat. They kept moving me around and one of the officials in the forces saw me there still at five o’clock. I’d got my ticket at eleven and he asked me why I was still there … He said, ‘Come with me,’ and he went in [to the ticket office], and he said, ‘This lady has got to get to Wagga.’

“Then and there I got a seat, and he said, ‘Don’t move for anybody; just stay there,’ so I got through like that.

“I was the only person in the family who got to Don’s wedding. I was a bridesmaid, all dressed up in blue.”

Merle, on the left, was one of the bridesmaids at Don's wedding.

The following February, Don was sent to 3 Operational Training Unit in Rathmines, New South Wales, where he trained as a flight engineer. He joined No. 20 Squadron in Queensland, working on the Catalinas, and returned to Melbourne in June 1944 for Merle’s wedding. She was marrying Robert Hare, a gunner in an anti-aircraft battery in the 9th Division who had served at El Alamein, Finschhafen and Lae.

“Don came down for my wedding in 1944, and the last time I saw him was on my wedding day,” she said.

“I went into Myers and the man there knew me because I used to do their pays. I said I was going to get married and I wondered what I could get for material. You had to get coupons to buy anything. He just called this boy over and said go up to the storeroom and bring this down. It was a great big thing of tulle and he gave it to me and said, ‘There you are; get your frock made of that.’

“My mum had a friend who was a great dress maker, and she took the whole thing. She was what was called a modiste in Collins Street, and she made my wedding frock for me.

Merle holding her wedding photo. The wedding dress was made out of tulle from the storeroom at Myers.

“My two sisters-in-law used it when they got married, and four of the girls in the WRANS knew about it. I don’t know how they knew, but they all wanted to borrow it, so my frock did a good job. I think six of us used it … and I was married at Sassafras in the little Methodist church.

“I only had seven days leave, and Bob had come out of New Guinea. He was up in the Atherton Tablelands because they were going to go to Borneo, and he only had 14 days’ leave.

“We stayed overnight at Monreale and then we went to Marysville for a so-called honeymoon... It was terribly cold, and when they went to New Guinea they had to take Atabrine to prevent them from getting malaria. Bob kept taking his Atabrine, so he didn’t get malaria, but what he got was dengue fever, so he spent the first five days of our honeymoon in bed … and I just walked around in the frost and the snow and God knows what else.

Merle's husband Bob. Photo courtesy of Merle Hare.

“When Bob came to, we went to dinner at the boarding house we were staying at. Half his gun crew, they all came from there too … and then all the stories started coming out about what Bob did in Africa and the Middle East. He was a lance corporal, and he just stood up, and he said, ‘Quiet, no more talk about that.’ I’ll never forget it… My brother and his wife had come down for the wedding, and that was the last time I saw him … I never saw him again.”

A few months later, Don moved to Darwin in the Northern Territory with No. 20 Squadron. The squadron flew Catalinas and was primarily engaged in laying mines to the north of Australia.

Don had flown 18 missions with the squadron and was the flight engineer on Catalina No. A24-203 when it left Darwin, bound for Jinamoc Island, on 1 March 1945. Arriving safely at the island, it left on the 7th of March for Lingayen Gulf, where it refuelled before taking off again almost immediately on an operational flight to lay mines in the South China Sea. It was never heard from again.

Searches were conducted in the area around south-east Formosa – known today as Taiwan – but no trace of the aircraft or its crew members was found. They were reported missing, and were presumed to have been killed in action on 7 March 1945.

Sergeant Don Storrie and Sergeant Alfred Russell Jones relaxing on the fuselage of a consolidated Catalina in Darwin Harbour. August 1944.

Refueling a No. 20 Squadron consolidated Catalina from a fuel barge in Darwin harbour.

Don (far left) and the crew of No. 20 Squadron viewing damage caused by an explosive bullet that passed through a fuel tank - missing fuel and oil lines - on their first mission. 20 August 1944. Darwin, NT.

It was a devastating blow for Merle and her family.

She was in Sydney with her husband and her sister when the war ended just five months later.

“We’d all gone up to the Blue Mountains for the day … and when we got back, we went into Martin Place, and everyone went mad,” she said.

“My sister had her hat knocked off, and when she went to pick it up, some fellow stopped her, grabbed it, picked it up, and rammed it on her head.

“Everybody was going nuts, and it was just unbelievable.

“We went back to our hotel that night for our evening meal, and Alma came with us. A lot of the top brass from the Army, Navy and Air Force were there … and they stuck my sister up on the table and sang Rose of No Man’s Land.

“I’ll never forget that. They were all very happy – very happy indeed – and it was an unbelievable feeling really, but I had lost my twin brother so I’m afraid I broke down, knowing he wouldn’t be coming back.”

Today, Don and his crewmates are commemorated on the Labuan Memorial in Malaysia and their names are listed on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial.

Merle named her son Don after him, and still has the letters he wrote to her during the war.

“I’d lost him in the March, and that was the worst thing that ever happened to me,” she said.

“It always has been, and it still is … but that’s all memories now, and life goes on.

“When you get to 100, nothing fazes you anymore.”

You can view more images from the Last Post Ceremony here.

Don's name on the Roll of Honour