The Lahey family

Left to right: Vida, Noel, and Romeo Lahey, 1916. (Beatrice “Bee” Belton, AWM P04598.001)

In 1914, 32-year-old Frances Vida Lahey was working as an artist at her studio in Brisbane. The eldest of 12 children, Vida, as she was known, had studied at the National Gallery School in Melbourne under prominent painters, Bernard Hall and Frederick McCubbin. In 1912 she exhibited her work Monday Morning to great acclaim. But the descent of Europe into war in 1914 changed everything for Vida.

Her youngest brother, John, known as Jack, enlisted for active service in the wake of the Anzac landing on Gallipoli in April 1915. The Lahey family owned one of the largest timber-cutting companies in Canungra, south of Brisbane. Nineteen-year-old Jack, like several of his brothers, was a saw-miller by trade. He arrived on the Gallipoli peninsula in October 1915 and soon became ill with enteric fever. Transferred to the 1st Australian General Hospital in Heliopolis, Egypt, Jack became so unwell that he was evacuated to Australia in early 1916.

After recuperating for several months, Jack returned to his battalion, which by this stage had moved onto the bloody battlefields of the Western Front. Two of Vida’s other brothers, Noel and Romeo, also volunteered to serve overseas. Romeo, a civil engineer, was posted to the 11th Field Company Engineers while Noel, a saw-miller, was posted to the 9th Battalion. Hoping to be closer to Romeo, Noel later requested a transfer to his brother’s unit.

In 1916, Vida abandoned her artistic pursuits and travelled to London to establish a home base for her brothers and cousins who had also enlisted. She soon became heavily involved in assisting with the war effort. She traced aeroplane parts, worked at the ANZAC Buffet in London, took servicemen who were on convalescent leave on outings, and helped with other Red Cross Society activities.

In June 1917, a combined allied force attacked a strongly-defended German position on the Messines–Wytschaete Ridge. The assault began with the detonation of 19 large mines under the German front line before the infantry advanced behind a carefully coordinated artillery bombardment.

Noel suffered multiple gun-shot wounds during the battle, and was admitted to the 9th Australian Field Ambulance. Romeo visited his brother in hospital but Noel died the following day and was buried at Pont D’Achelles Military Cemetery, near Armentières.

Though mourning the loss of their brother, Jack, Romeo, and Vida continued to serve. Several months after Noel’s death, Jack was injured again and invalided to Australia. Romeo remained on the Western Front, where he saw action at Zonnebeke, Villers-Bretonneux, and during the final advance to the heavily-fortified Hindenburg Line.

When the guns fell silent on 11 November 1918, London burst into joyous celebrations. Vida saw euphoric crowds gather on the streets but her joy was tempered with the knowledge that one of her brothers would never return to Australia. Romeo remained close by and during the long wait for repatriation attended a town-planning course at the University of London’s School of Architecture.

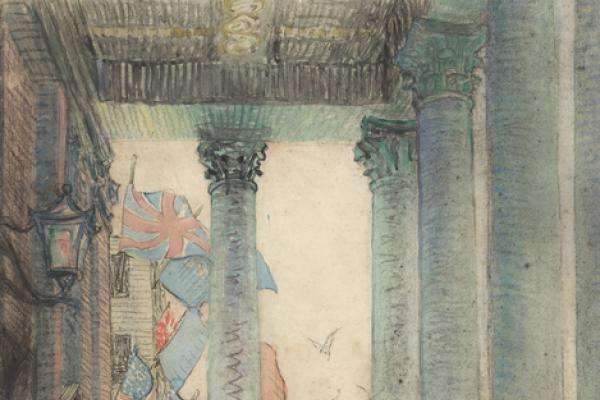

He returned to Australia in May 1919. Vida stayed in Europe, travelling to the Netherlands and France, and rekindled her passion for art. She returned home in 1920 and became a well-known and respected artist. Vida recorded the celebrations she had witnessed at the end of the war in a painting titled Rejoicing and remembrance, Armistice Day, London, 1918.