Kath Walker (Oodgeroo Noonuccal)

Born in 1920, Kathleen Walker, nee Ruska, grew up on North Stradbroke Island in Moreton Bay, east of Brisbane. Known as Kath, Walker showed a natural gift with words at an early age and was encouraged to pursue writing at school. Her father, Edward, worked for the Queensland government and campaigned relentlessly to improve conditions for Aboriginal employees.

Walker left school in 1933 at the height of the Great Depression to take up work in domestic service. When the Second World War broke out in 1939 two of Walker’s brothers, Eric and Eddie, enlisted for service in the army. Both were captured by the Japanese when Singapore fell in February 1942, and they spent the next three and a half years as prisoners of war.

In December 1942 Walker joined the Australian Women’s Army Service (AWAS) and trained as a signaller. In that same year she married her childhood friend, Bruce Walker, who was a talented bantamweight boxer and a welder by trade. Kath remained in the AWAS until early January 1944. She settled in Brisbane with her husband, and their first son, Denis, was born two years later.

Both Eric and Eddie survived the war and returned home to Australia. Eddie, who had been a promising sportsman, had lost his right leg during his imprisonment. Walker separated from her husband soon after the war and returned to domestic service to support her son. She gave birth to a second son, Vivian, in 1953.

In the 1960s Walker began to develop a reputation as a poet, and published three critically acclaimed collections. Around this same time she became an increasingly passionate advocate for Aboriginal rights, and worked towards reconciliation for the remainder of her life.

In 1970 Walker was appointed a Member of the British Empire for her services to Aboriginal people. Now known by her traditional Aboriginal name, Oodgeroo Noonuccal, she returned her award some years later in protest against the celebrations planned to mark 200 years since the arrival of the first convict ships in Australia.

She died in 1993 at the age of 72. A trust was established in her honour to carry on the work she had begun towards reconciliation.

Activities for research and discussion

1. At least nine Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women served with the AWAS, while another three joined the Australian Women’s Land Army. What is the purpose of this poster? Who is it designed for? What kinds of techniques have been used to appeal to that audience?

Maurice Bramley and Department of National Service, Join us in a victory job, c. 1943

2. Women made a significant contribution to Australia’s war effort during the Second World War. How might they have been able to offer assistance? Why were so many women needed for different roles?

3. Official war artist Murray Griffin was among the thousands of Australians, including Walker's brothers, captured by the Japanese when Singapore fell in February 1942. As an officer, Griffin was exempt from forced labour, and was therefore able to continue his work as an artist during his imprisonment. What does this drawing suggest about the prisoner-of-war experience for Australians held captive in Changi? What are some of the challenges they may have faced? Imagine you are one of the soldiers in this drawing: what might you have done to cope during this difficult time? You might also like to watch the footage below which was filmed at Changi after the war.

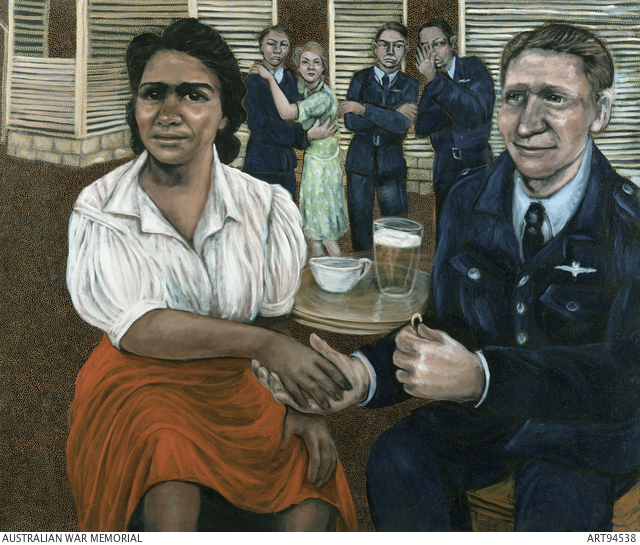

4. Julie Dowling’s painting The Dance depicts the marriage proposal between her grandparents, and also explores widely held attitudes towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people during the Second World War. How has Dowling captured this mood in her painting?

5. How do you think women like Walker may have felt about returning to civilian life after serving in the war?

Return to Memorial Box 3 supporting resources