Douglas Grant

Douglas Grant was born into a remote Aboriginal community in Far North Queensland around 1885. It is presumed that Douglas was from the Ngadjonji nation, in the Bellenden Ker Ranges in the Atherton Tablelands.

There were recorded and unrecorded frontier conflicts in the area, as white miners who were looking for gold came into contact with Aboriginal communities. Several massacres took place, including one which gave name to a place called Butchers Creek. It has been suggested that the number of people killed in Queensland’s frontier wars was similar to the approximately 60,000 people killed while serving Australia in the First World War. It was during one of these conflicts that Douglas’s family and community were killed by the Native Police. Although Native Police forces included Aboriginal people, they were created by the state, and commanded by white Australians.

Scottish scientist Robert Grant and his wife, Elizabeth, were on an expedition in the area, collecting birds and mammals for the Australian Museum in Sydney. The Grants came across a young boy who had survived one of the massacres. They decided to take him to their home in New South Wales, even though it was illegal to move Aboriginal children across state borders at that time.

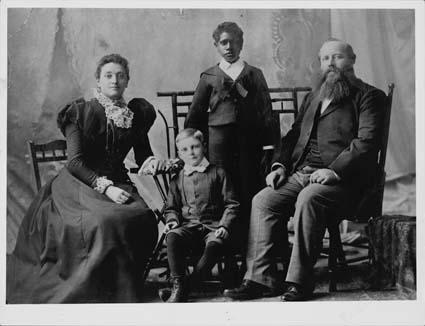

Adopted and raised by the Grant family, the boy was given the name Douglas. He spent most of his childhood in Lithgow, and then the Sydney suburb of Annandale, with Robert, Elizabeth, and their biological son, Henry. Douglas attended Annandale Public School, where he developed a love of Shakespeare and poetry. He was also a talented artist, winning first prize in the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee exhibition for a drawing of the bust of Queen Victoria in 1897.

Douglas Grant with his adoptive family, c. 1896. National Archives of Australia, Canberra, SP1011/1, 2176. Reproduction courtesy of the National Archives of Australia and Australian Broadcasting Corporation Library Sales.

After finishing school, Douglas pursued his interest in drawing, training as a mechanical draughtsman. He worked in this role at Mort’s Dock in Sydney for ten years, before accepting a job as a wool classer at the “Belltrees” station in the Upper Hunter Valley. When the First World War broke out in 1914, Douglas and some of the other station workers decided to volunteer for active service.[1]

Douglas enlisted with the 34th Battalion in January 1916, though it is unclear how this occurred at a time when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were excluded from military service. Journalists were very interested in Douglas’s enlistment, with the Sydney Mail suggesting that he was an example of what could be achieved through assimilation.[2]

As Douglas was about to leave Australia, the Aborigines Protection Board intervened, noting that regulations prevented Aboriginals from leaving the country without government approval. The authorities eventually gave permission for Douglas to travel, but by that point he had been transferred to the 13th Battalion, and had lost his rank of sergeant.

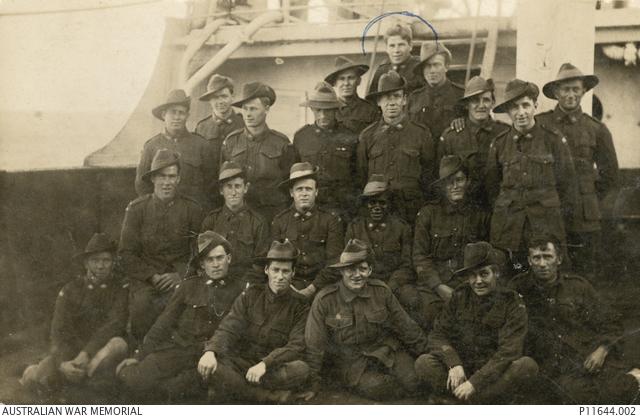

Soldiers returning to Australia, including Private Douglas Grant (middle row, fourth from left), 1919.

Upon completion of his training, Douglas was sent to the front lines in France. On 11 April 1917 he was wounded and captured at Bullecourt. This battle was one of the most costly actions undertaken by the Australian Imperial Force in the First World War – at least 3,000 men were killed or wounded and a further 1,170 were taken prisoner.

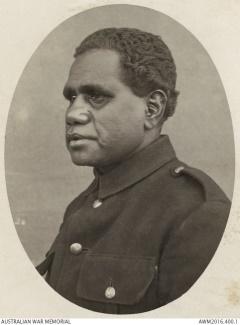

After his capture, Douglas spent several months in France with the other Bullecourt prisoners, who were used as forced labourers for the German Army. Owing to his dark complexion, history as an Aboriginal man educated in a white society, and even his ability to put on a Scottish accent, the Germans were very curious about Douglas. He ended up at the Wünsdorf camp in Zossen, which was described as “half science laboratory and half colonial propaganda camp” [3].

Prisoners were also studied by scientists, who documented information including their skull measurements, languages, and traditional songs. [4]

Douglas Grant as a prisoner of war in Germany, c. 1917–18. (AWM2016.400.1)

Douglas was popular among his fellow prisoners, cherished as a remarkable figure who proved to be both honest and quick-thinking. He was given the responsibility of receiving and distributing Red Cross parcels. He was in regular contact with the secretary of the prisoners of war Branch of the Australian Red Cross Society, Miss Elizabeth Chomley, who was a vital link between prisoners in Germany and their families in Australia. Douglas wrote to her in 1918:

"I am happy to say that I am enjoying perfect health, but as it is only natural I long and weary for Home which I trust may soon be within measurable distance. Please accept many thanks for past favours" [5]

Douglas’s role in distributing comforts was an extremely important one. Not only did the parcels provide essential nutrients and lift the men’s spirits with much-needed goods, but the system also provided the opportunity to accurately record who had been taken prisoner and where they were held. This vital information could make a huge difference for families at home in Australia who were waiting for news of their “missing”.

After the war, Douglas returned to his job as a draughtsman, and later found work at the Lithgow Small Arms Factory, collected natural specimens for various museums, and dabbled in taxidermy like his adoptive father and brother.

Although Douglas had experienced a degree of equality during the war, this did not continue when he returned to Australia. June Madge, a descendant of the family, remembered that at one point Douglas was asked to leave the pub when other patrons complained to police that an Aboriginal man was drinking there.[6]

Douglas lobbied for Aboriginal rights and became active in returned servicemen’s affairs. He wrote various opinion pieces for the newspapers, conducted a radio show, and urged the government to protect the lives of Aboriginal people. As the years passed, Douglas became a heavy drinker, and struggled with his mental health. He spent some time in the ex-servicemen’s ward at Callan Park Mental Hospital in Sydney, where he also worked as a clerk. After leaving Callan Park, Douglas lived with his younger brother, Henry. He was later declared unfit for work.

Douglas struggled to find his place in Australia after the war. On one Anzac Day in Sydney, as ex-serviceman Roy Kinghorn made his way to the service, he noticed Douglas outside the Domain. Roy encouraged Douglas to attend, but Douglas said to him:

“No I’m not wanted anymore … I think I’m better out here … I’ve lived long enough to see that I don’t belong anywhere, and they don’t want me.”[7]

Roy took Douglas by the hand and led him into the Domain, where they attended the service together.

Douglas died at the war veteran’s home in La Perouse in 1951. Douglas Grant Park in Annandale, New South Wales, was named in his honour in 2015.

[1] “Sergt. Douglas Grant: dark skin but white heart”, <accessed 14 October 2019>

[2] “An Aboriginal soldier”, <accessed 14 October 2019>

[3] Tom Murray, “Douglas Grant: the skin of others”, ABC Radio National Earshot, 2017, <accessed 4 September 2019>

[4] Tom Murray, “Douglas Grant: the skin of others”.

[5] Tom Murray, “Douglas Grant: the skin of others”.

[6] Tom Murray, “Douglas Grant: the skin of others”.

[7] Tom Murray, “Douglas Grant: the skin of others”.

References