The Simpson Prize 2019

The Question

To what extent could 1918 be considered a year of victory for Australia and its people?

Instructions

The Simpson Prize requires you to respond to the question above using both the sources below and your own research.

You are encouraged to agree with, debate with, or challenge the statement from a variety of perspectives—individual, national and global—and to use sources in a variety of forms.

You are expected to make effective use of a minimum of three of the following sources. Up to half of your response should also make use of information drawn from your own knowledge and research.

Information about word or time limits, the closing date, entry forms and judging can be found at the Simpson Prize official website.

Note: students who submit winning entries for this year's Simpson Prize question will travel in 2019.

The sources

Source 1: Artwork

"8th August 1918"

The Battle of 8 August 1918, showing the Australian Artillery moving forward from Villers-Bretonneux. Horse drawn artillery and tanks - at right is a British Mark V tank - can be seen moving forward. In the centre of the work there is a column of German prisoners of war with an armed escort. The prisoners are carrying a wounded man on a stretcher. A German 77 mm M16 fieldgun and dead crew are visible on the right. This work depicts part of the allied offensive of the day that became known to the Germans as 'der schwarze Tag' or the black day.

Source 2: Photograph

Armistice celebrations in Martin Place, Sydney

Sydney, New South Wales. 11 November 1918. Crowd in Martin Place celebrating the news of the signing of the armistice. This date was celebrated in later years as Remembrance Day.

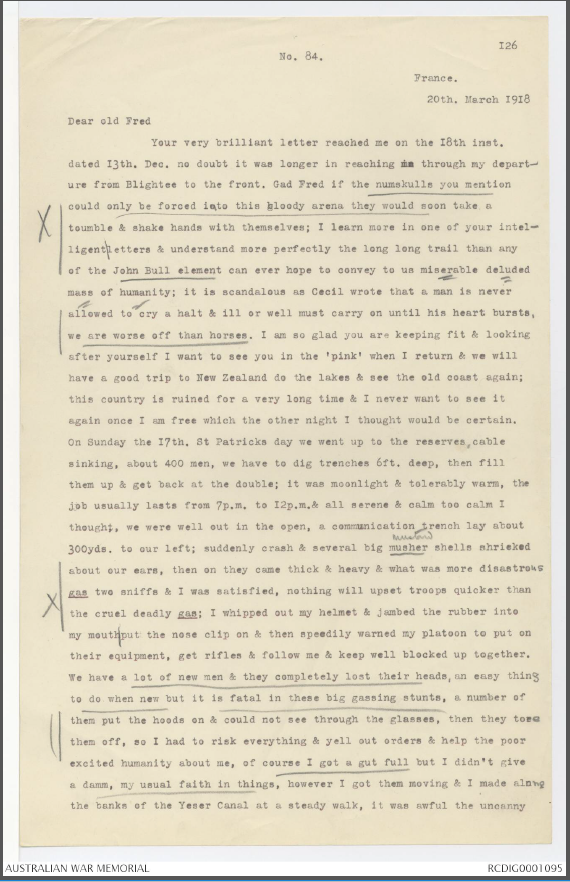

Source 3: Letter

"[W]e were well out in the open … suddenly crash & several big musher [high explosive] shells shrieked about our ears, then on they came thick & heavy & what was more disastrous gas two sniffs & I was satisfied … I whipped out my helmet & jambed the rubber into my mouth put the nose clip on & then speedily warned my platoon to put on their equipment … We have a lot of new men & they completely lost their heads, an easy thing to do when new but it is fatal in these big gassing stunts, a number of them put the hoods on and could not see through the glasses, then they tore them off, so I had to risk everything & yell out orders & help the poor excited humanity about me, of course I got a gut full but I didn’t give a damn, my usual faith in things, however I got them moving … at a steady walk, it was awful the uncanny feeling of death eating at ones entrails and the gasping of the men trudging behind you, the thunder of the shells, & the fires from the dumps showing ghostly through the gas smoke, a bluish vapour hanging like a pall … [For more than an hour, we] just kept on through a veritable hell let loose; it was my job to get my men treated for gas, many of them starting to tumble about as though they were drunk … we reached the hospital & each man exhausted & fearfully windy was given a drink of ammonia which is supposed to have a beneficial effect; however two men died from the gassing, weak hearts you see, poor devils it is terrible & the horror of it; yet we all had to go up again the next night & carry on as usual."

Source 4: Photograph

Near Bois de l'Abbe, France. 27 May 1918. Gassed Australian soldiers lying out in the open at an over crowded aid post near Bois l’Abbé. They have been gassed in the operations in front of Villers-Bretonneux. (Note by Sergeant A. Brooksbank, Gas NCO, 10th Australian Infantry Brigade: Examples of what should not be done. Casualties should have removed contaminated garments. Lying on the ground with contaminated clothes and not wearing respirators means that they are inhaling quantities of vapour and adding to their injuries).

Source 5: Photograph

Southall, England. A group of disabled AIF members attend the Australian Red Cross Society’s workshop.

Source 6: Photograph

Lieutenant Rupert Frederick Arding Downes MC addresses his Platoon from B Company, 29th Battalion on 8 August 1918 during a rest before the advance onto Harbonnieres, the battalion's second objective. They are near the villages of Warfusee and Lamotte, France.

The background of the photograph is obscured by the smoke of heavy shellfire. Many of the men pictured were killed in action or died of wounds or disease in the days and weeks after the photograph was taken, being amongst the last Australian deaths during the First World War. Each man has a story. Pte Towers (fourth from right), for example, was a farm labourer of Cootamundra, NSW, who later transferred to the 32nd Battalion. He was admitted to the Abbeville Hospital on 9 November 1918 suffering broncho-pneumonia where he died on 11 November 1918.

To find out what happened to the other men in the photograph, see: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1251.

Source 7: Official records

Source 8: Photograph

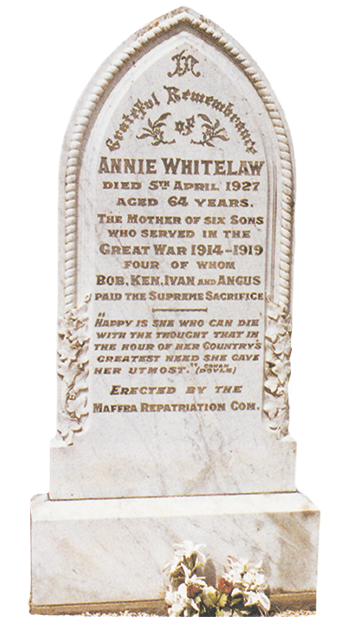

Tombstone of Annie Whitelaw.

The epitaph on the grave of Annie Whitelaw suggests a great deal about life for her in the post-war world.

Headstone of Annie Whitelaw

Photo credit: ‘Australia’s War Heritage, Local Graves’, Anzac Portal, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Australia.