Assault by fire

Pte Arthur Leslie Willett, 2/8 Infantry Battalion, using a flame-thrower against the Japanese at Wewak, 10 May 1945.

The trench fills with flames, sparks, acrid smoke, it's impossible to breathe. I hear hissing, pattering, and alas yes, the cries of pain. At my feet two miserable creatures are rolling on the ground, their clothes, their hands, their faces on fire like human torches. And in the trench everything is on fire: blankets, tents, sandbags. The Germans had just fired some sort of incendiary liquid on us.

So wrote Louis Barthas in his memoir of the First World War. Termed Flammenwerfer by the Germans, or lance-flammes by the French, the concept of hosing liquid flame onto an enemy was as old as warfare itself. The 5th century BC Greek historian Thucydides, for example, described an elaborate device being successfully used by the Boetions to blast flames against the timber ramparts of the city walls of Deleon:

They sawed in two and hollowed out a great beam, which they joined together again very exactly, like a flute, and hung a cauldron at one extremity by chains … [then] inserted huge bellows into their end of the beam and blew through it. The blast passed into the vessel which contained burning coals and sulphur and pitch; these made a huge flame, and set fire to the rampart, so that no one could remain upon it.

The Byzantine Empire of the early medieval period similarly combined a mysterious mix of liquids to produce ‘Greek fire’, a composition that was reputed to be inextinguishable, and greatly feared in naval battles.

‘Greek Fire’ was reputed to have been inextinguishable and its use was especially feared in naval battles. Image courtesy of Wikicommons.

It was the advances of the industrial age, however, that saw the flame-thrower mature into a mass-produced weapon with accuracy, range, reliability and a high degree of operator safety. In its early 20th century form, as initially developed and fielded by the pre-war German army, coal tar and benzene contained in a steel tank carried on a soldier’s back was forced through a lance by pressurised gas. The flammable liquid was then generally ignited by a flare or match contained in the muzzle of the lance.

The physical effects of the weapon on the human are understandably frightful – direct contact with the burning liquids and flame causes death or serious injury, and close proximity to the flame plume can bring about respiratory failure from breathing superheated air or inhaling toxic fumes. Where the weapon is directed against enclosed bunkers or shelters, the flames can suck out the oxygen, suffocating the occupants, or produce toxic levels of carbon monoxide. The weapon can also be used in an anti-material role, flames clinging to trench supports and sandbags, dripping into dugouts and setting fire to bunker supports or a vehicle’s engine or rubber components.

Possibly the greatest effects of the weapon are psychological: it draws on the most basic of mammalian responses to involuntarily flinch and flee from heat and fire. One of the co-inventors of the weapon, Bernhard Reddemann, vividly described the panic caused on 26 February 1915 at Malancourt near Verdun.

Loud screams of pain come from the enemy on the other side. Those who are not caught in the flames jump back out of the trench. They run heedless across open ground without cover. Running back through the communication trenches, there’s no time for that! Away, away from the terrible flames! They leave everything behind, even their guns! Unconcerned by the machine-gun fire from our infantry, they run across open terrain.

Encounter by British

Reports of its first use produced shock and revulsion in the allied press, with claims that the ‘inhuman’ and ‘fiendish’ enemy was breaching international law. The first British unit to encounter the weapon was the 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade. The unit had been one of the first battalions of Kitchener’s New Army to be sent to the firing line, and in little over a month had already suffered heavy losses. On 30 July 1915, the unit took over the trenches at Hooge, 2 km east of Ypres, near the ruins of what the men called the Gingerbread Chateau. Entering the trenches on a dark night, the Battalion’s strength was 24 officers and 745 other ranks. Two companies were emplaced in trenches running 20 metres north and parallel to the Menin road, while a further two companies were in reserve about 500 metres to the south, in Zouave wood.

Unfortunately, the battalion’s position was a weak one: the front line trenches were deep and narrow and crammed with men; many of the support trenches had recently been destroyed by German trench mortars and were not habitable. Communication to the rear was difficult; there was no barbed wire in front; and a massive crater divided the two front line companies. The crater had bomber’s posts established on each side, but the front of the crater was not held.

Co-ordinated use by the Germans of multiple static flame-throwers and fast-moving assault parties exploited these weaknesses.

Suddenly sheets of flame broke out all along the front with clouds of thick black smoke. The Germans had turned on liquid fire, from hoses apparently, which had been established just in front during the night. Under cover of the flames, swarms of bombers appeared on the parapet and in the rear of the line. … The fighting became very confused and the machine guns were soon all out of action. (8th Battalion Rifle Brigade War diary, May 1915)

The extreme right and left platoons had not been affected by the flames, but were surrounded and cut off. At 4 am ‘B’ Company in Zouave Wood counter-attacked and was beaten back, but established itself near the trench and crater which the Germans had just captured. Here they were able to cover the withdrawal of a few remnants from the platoon under the command of Lt Stanley Woodroffe, who was later awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his gallantry during the action.

The Germans quickly advanced about 250 metres and established themselves south of the Menin road in the ruins of Hooge, cutting the battalion in half, and attempted to force their way down two communication trenches (‘Old Bond Street’ and ‘The Strand’) with grenades. The trench was blocked halfway up and the southern ends held. The non-engaged elements of the battalion in Zouave wood were meanwhile being subjected to violent artillery bombardment, which cut telephone lines and prevented the battalion from uniting.

Reinforcements from the 7th Battalion Kings Royal Rifle Corps arrived at 9 am, but by the time a counter-attack was launched at 2.45 pm, the 8th Battalion had only one extant organised company from the four that had been in position 12 hours before. The counter-attack pushed up along the lines of the communications trenches but failed halfway towards its objective. The men were able to hold onto their ground until dark, and the entire Battalion was taken out of the line at 2 am. In 23 hours the attalion had suffered 499 casualties: 9 officers killed and 10 wounded, 80 other ranks killed, 132 missing, believed killed, and 267 wounded. The effect of a shocking massed ‘liquid fire’ attack, with a co-ordinated attack by grenade-carrying infantry on a clearly identified weakness of line, had produced a devastating result.

Types of flamethrower

Germany had initially fielded two flame-thrower types, a fixed heavy emplaced weapon operated by five men (the grosser Flammenwerfer or Grof) and smaller man-packed versions (the kleiner Flammenwerfer or Kleif). It is uncertain which type was used in the attack at Hooge. The Grof could project its stream of flame for 45 seconds, with a range of up to 45 metres, while the Kleif’s duration was 20 seconds, with a range of 20 metres. The Kleif was intended to be used by two men, with one carrying the tank on his back, and the other carrying and aiming the lance. With a fuel tank capacity of 19 litres, the Kleif weighed just over 31 kilograms fully laden. Later modifications, which saw it redesignated as the medium mittlerer Flammenwerfer, gave it a range of up to 32 metres. Germany continued refinement of its Flammenwerfer throughout the war. In 1917 a new lighter design, the Wechselapparat (Wex) M 1917 was introduced, which could be carried and operated by one man. This gave German assault pioneers considerable flexibility of movement and relative speed.

Lieutenant Leslie Bowman Cadell, 6th Battalion, holding a German Wechselapparat (Wex) M 1917 flame-thrower captured near Stirling Castle in the Ypres sector.

By the time the first Australian battalions had arrived in France, the Flammenwerfer was an established element in the German arsenal. But for all its effectiveness as a weapon which could create panic and terror, it remained cumbersome to carry, operate and refuel. It was fairly quickly determined also that it could only be used for planned deliberate attacks, rather than opportunistically. Further, as Entente troops became more accustomed to Flammenwerfer attacks, so too they recognised their vulnerabilities, and developed specific techniques for countering them. In snowy conditions, for instance, the Flammenwerfer melted the snowfalls and marked out the operators as targets for snipers. The French army also improvised light-weight oblong protective shields covered with clay, which gave protection from the burning fuel if not from the heat and suffocating fumes. Contemporary accounts indicate that these shields were well regarded, but they must have taken considerable nerve to use.

The weapons also posed considerable dangers to their operators, as the Flammenwerfer’s short range meant that the operators were extremely vulnerable to counter-fire. A French account from March 1916, widely reported in contemporary Australian newspapers, related how “the swine ... stood with their legs apart, exactly like firemen, 20 yards from our trenches. The Seventy Fives [French 75 mm artillery] made havoc of the attack. One shell exploded on a juice container and tore a hole. The blazing liquid caught the big Boches, who ran screaming in all directions.” The author thought that flame attacks against French trenches supported by artillery were worse than useless, as “we had less than 70 men burned altogether.”

An attack against Australian troops in May 1917 at Noreuil on the Hindenburg Line had similar outcomes for the Flammenwerfer crews. The weapons were at first used to great effect, playing on the trenches, with supporting troops shooting down any who tried to escape over the top. But as the German advance continued and the fighting became more confused, Lieutenant Alexander MacNeil of the 3rd Australian Light Trench Mortar Battery seized a Lewis gun, and wormed his way from shell-hole to shell-hole towards the approaching enemy. He waited until the man with the Flammenwerfer – his attention concentrated on the trench before him – had advanced a few metres past him. MacNeil then stood up, and firing from the hip emptied the Lewis gun into the Flammenwerfer operator and those accompanying him. As the Flammenwerfer operator fell, the nozzle of the machine turned back upon his own comrades, and caused the rest to retire. Badly shaken, the Australian infantrymen were slow to realise that the Flammenwerfer attack had ended; even so, before the Germans could reorganise, MacNeil rallied his men and counter-attacked. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Order, having intitially been recommended for the Victoria Cross.

Allied use

The new weapon was met with widespread revulsion within the allied armies on the ground and in the press. Despite this, its tactical benefits were quickly appreciated by all the combatant nations, with most developing and using a variety of portable and static flame-throwers. The British even agreed in 1915 that flame-throwers could be sent to Gallipoli. Although that never transpired, Britain nonetheless produced the largest flame-thrower of the war, the 2.5-ton Livens Large Gallery Flame Projector, with a fuel capacity of 1,090 litres and a range of 102 metres. Developed by Captain William Livens of the Royal Engineers, four such machines and 24 smaller flame-throwers were intended to be used on the first day of the battle of the Somme in 1916.

Bringing the devices up to the front lines was a mammoth logistical undertaking. Shipped from Southampton to Le Havre, the flame-throwers, oil and compressed gas supplies went by rail to Corbie and were loaded onto Royal Engineer lorries. Near Bray-sur-Somme, the units were reloaded onto 3-ton lorries and then onto horse-drawn GS wagons, with each unit filling 10 wagons. The wagons were brought as close to the front lines as possible, and were taken by a 200-strong carrying party of infantry. One of the projectors met with bad luck – as the long and heavily laden carrying party moved slowly through a communication trench, the column “collided with a party of [German] pioneers with picks and shovels”, and was then subjected to a heavy bombardment. Parts of the flame-thrower were dropped, but the most important parts were rescued and placed in an underground shallow gallery – minutes before the entrance to the gallery was sealed by a heavy German shell. The flame-thrower remained buried until it was excavated by archaeologists in 2010. Another flame-thrower was damaged by shellfire, but the remaining devices were emplaced as planned.

At 7.16 am on 1 July one shot was fired by each of the two surviving projectors, with the flame reaching well over the German trenches in each case. Post-battle analysis concluded that the weapons had been largely successful, as when the infantry attacked, the casualties were much fewer on the width of the flame front than on the flanks. Several charred enemy bodies were discovered in the trenches opposite the devices, and the officer commanding one of the units personally captured (and gave medical assistance to) 50 German survivors.

Much more simple ground-emplaced projectors were also developed by Lt Harry Strange and Livens at Sailly le Sec, and used at the Somme from mid-July 1916. These were not strictly flame-throwers, but large drums which could throw a 3-gallon canister of flammable oil. Once fully developed, they were adapted to firing gas shells. Various man-portable flame-throwers were developed by Britain but were rarely used in the field. None of the 24 semi-portable flame-throwers brought to the Somme trenches in late June 1916 were brought into action for the opening battle, as it had been found nearly impossible to negotiate trenches with the weapons. The Royal Engineers concluded that the devices could only be used for attacks on and domination of mine craters (as happened at Hooge), for very close fighting in redoubts, and for defence of strong points. No type of flame-thrower was considered suitable for open fighting, given that the maximum range was 40 yards. The Royal Engineers recommended that if a flame-thrower was needed in crowded trenches, it had to be a small: no more than 80 pounds (36 kg) fully charged, and able to be quickly assembled from small, light parts.

Perhaps the most notable action in which Britain used flamethrowers was the Royal Navy’s raid on the Belgian port of Zeebrugge on the night of 22 April 1918. The raid aimed to disable the German U-boat base, which posed a serious threat to allied shipping in the English Channel and North Sea. The obsolete warships HMS Vindictive and Iris II both carried assault parties to storm the harbour mole and attack the German defences. Vindictive carried two five-man Vincent flame-throwers, and number of portable Hay flame guns, to provide protection for the landing party. To commemorate the part taken by Royal Australian Navy personnel in the raid, the British later presented one of the Hay flame guns used in the action to Australia; the gun is now at the Australian War Memorial.

One of the Hay flame guns used at Zeebrugge is now in the collection of the AWM.

One of the Hay flame guns on board HMS Vindictive. IWM Q 55569

The gun is missing its lance, but it retains evidence of its last action: shrapnel holes though its fuel tank. It is clearly heavier and more awkward to carry than the contemporary German machines. The operator slung the Hay Flame Gun from a shoulder strap so that it hung in front of his chest. He pressed a button on a dry-cell battery mounted on the lance, which ignited a port fire under the nozzle, giving a range of 20 metres and enough fuel for 15 seconds of firing. The flammable oil was pressurized with air pumped directly into the tank.

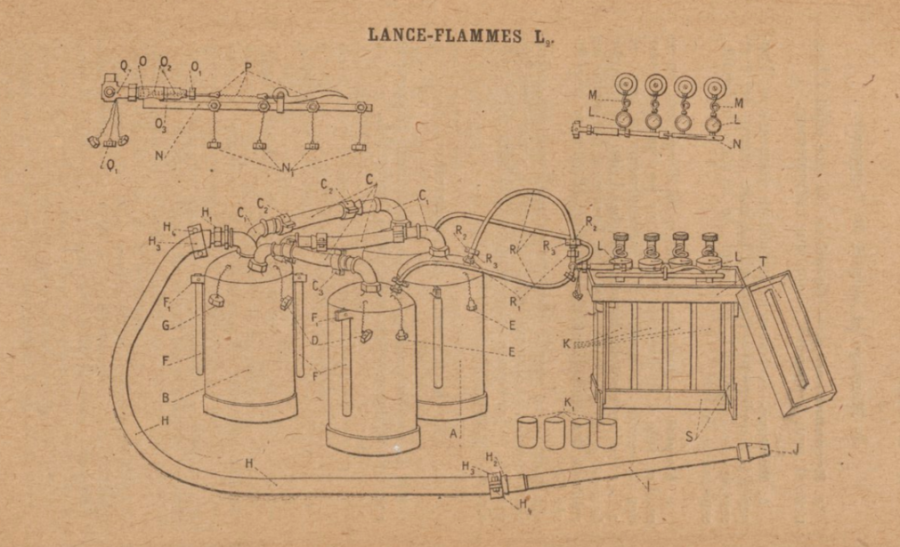

Having had intimate experience with the devastating effects of the Flammenwerfer, France embraced the invention, producing and fielding heavy static weapons such as the Shilt 1 and 2, and the Appareil L1 and L2, as well as portable weapons from as early as 1915. The most numerous type produced by the end of the war was the backpacked Appareil P3, with a tank holding 13 litres. By the end of the war, considerable thought had been given to doctrine, and a number of flame-thrower units were established, each consisting of three officers and 137 men, with 1 Appareil L1, three Appareils L2, 70 P3 devices, 2 cars, 6 trucks and equipment to re-charge the machines.

The French Lance Flamme; Paris 15 April 1917.

Although the use of the flame-thrower is most commonly associated with Germany, those who encountered it clearly were defined by it. In his classic anti-war novel All quiet on the Western Front, Erich Maria Remarque gives a harrowing account of facing the French lance-flammes:

We're in a hole and we're surrounded. The stench of oil or petroleum wafts over with the fumes of powder. Two men with a flame-thrower are spotted, one carrying the cylinder on his back, the other holding the pipe: here the fire shoots out. If they get close enough to reach us, we’ve had it, because we can't go back right now. We fire at them. But they work their way closer and it gets bad. … The second man with the flame-thrower is wounded, he falls, the pipe is wrenched out of the other one’s hands, the fire sprays in all directions, and the man is on fire.

Later wars

Despite being reviled as an enemy invention of questionable morality, the flame-thrower saw constant refinement, and in both vehicle-mounted and backpack versions it came to be relied upon by all combatant forces in the Second World War as a means of overcoming fortified posts. Australian troops used the weapon extensively in May 1945 during the Aitape–Wewak campaigns to overcome dug-in Japanese troops, and also used Matilda tank flame-throwers in the Borneo campaign.

A Japanese flame-thrower captured by Australian forces at Milne Bay in August 1942.

Flame-throwers continued to be used throughout the Cold War conflicts in Korea and Vietnam, typically only when all other methods had failed. Their first use in Vietnam by Australian forces, in July 1969, exemplifies the courage needed to use the weapon in close combat. A well-armed enemy battalion headquarters position, entrenched in bunkers and caves, had pinned down elements of A Company, 5RAR, wounding an officer and several men. Despite repeated attempts over many hours, the officer could not be extracted. Assault Pioneer Corporal Bill Ward was helicoptered into the contact area with a flame-thrower and came under immediate enemy fire. Ward reached a position within twenty yards of the enemy position, but because of the terrain, had to stand up to use the weapon, bringing immediate and heavy enemy fire against himself. On his first attempt to use the flame-thrower, the weapon misfired. Ward, still in his exposed position, remedied the fault and then delivered effective flame into the enemy strongpoint, enabling the rescue of the wounded officer. Ward received the Military Medal for his bravery.

Long range precision stand-off missiles, often guided by laser or GPS, and thermobaric (fireball) weapons have possibly largely left the man-pack flame-thrower behind; as well, the use of relatively imprecise ‘flame’ or area weapons is typically seen (in the West) seen as politically and morally indefensible. But as the ongoing war in Ukraine shows, the supply of expensive and technically complicated munitions can pose significant issues. It remains to be seen whether the simple back-pack flame-thrower might yet return to use, particularly for close combat trench and tunnel fighting and in urban areas.