"One Ilan man"

The Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion brought pride and unity to a disadvantaged group of Australians, as they prepared to defend their homes from the Japanese

Far up a remote river in Dutch New Guinea, in December 1943, an Australian patrol ran into two boatloads of Japanese soldiers. In the skirmish that followed, the Australians drew upon a long tradition as warriors. They were unusual. At a time when Australian policy was that enlisting non-Europeans was neither necessary nor desirable, these men were Torres Strait Islanders. They were members of one of the very few racially-based units in Australian military history, the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion.

Inspection of Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion, Thursday Island, 1945. C202332

The fourteen inhabited islands of the Torres Strait are home to a proud and diverse group of people. Their warrior ethos was essential to each island group's survival, since raiders from other islands sometimes threatened a community's very existence. Japan's entry into the Second World War changed everything. A common enemy threatened Australia and the Torres Strait lay in the path of any invasion from the north. For the first time the Islanders saw themselves as "one ilan [island] man". Joining the Australian Army, they prepared to draw on their own warlike past to defend their tropical home. For the Torres Strait Islanders, the Second World War gave birth to a unity they had never known before.

Officers of the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion, Thursday Island, 1945. Commanding Officer Major C.F.M. Godtschalk is third from right. C202338

Approval for raising an indigenous unit in the Torres Strait had been given in May 1941. The prospect of Japan entering the war alarmed planners, who knew that there were far too few troops available to defend against a Japanese advance. An indigenous garrison unit would free up other soldiers to be sent to New Guinea. However, there were concerns in military circles as to whether the Torres Strait Island men would be able to conform to the rigid discipline of the soldier. In giving approval, the Acting Prime Minister cautiously wrote:

Investigations here indicate that the Torres Strait Islanders would be well suited to be trained for military service and that there would be numerous volunteers forthcoming for such service at Thursday Island. As indicated in your letter of 14th January, the Director for Native Affairs would raise no objection to the recruitment of the Islanders. Approval has been given in principle to the raising of one company of Torres Strait Islanders for service on Thursday Island for the duration of the war and twelve months after.

In time, this initial company grew into the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion.

Recruiting was slow at first because it was the pearling season and many young men were out on the boats. At the start of 1942, with the pearling season ended, the number of recruits quickly rose to 830, from a population of less than 4,000. The men were organised into companies according to their island of origin:

A Coy - Murray, Darnley, York and Stephen Islands

B Coy - Badu, Moa and Mabuiag Islands

C Coy - all the above

D Coy - Saibai and Boigu Islands (the two most remote islands)

A variety of units from all services arrived from the south to bolster troop numbers in the area. Many of the southern soldiers had never met a Torres Strait Islander before, but now each group was able to gain an appreciation of the other. The Islanders appreciated the lifestyle and discipline of the Army, which allowed them to be treated with equality and respect. Soldiers took them on their merits, uninfluenced by the colour of their skin. As one Islander recalled, "when war e come, white and black become one people."

Harold West, of the 17th Australian Field Company, remembered working with the Islanders:

The way they weighed into laboring jobs was an inspiration. They were big, happy, confident fellows, in no way acknowledging white supremacy and we for our part, did not claim any. We met as equals and got on famously. They were marvelous singers [and] also treated us to an occasional wild and energetic dance.

Lowering of the colours ceremony, Thursday Island, 1945. C202352

The military hierarchy, on the other hand, did not share these ideas about equality. The Islanders were paid about one-third the amount paid to non-indigenous soldiers.

Troops in the area did not realise how close the Japanese were until the first air raid pounded Horn Island on 14 March 1942. Seven further air raids on the island and numerous aerial reconnaissance missions followed. By the end of 1942, there were 5,000 Australian troops on Horn Island, 2,000 on Thursday Island and hundreds more on the outer islands. In addition, hundreds of American aircraft and servicemen began to arrive.

The Torres Strait Light Infantry trained as an infantry unit, exercising in the jungle on Prince of Wales Island with the 5th Machine Gun Battalion and the 26th Battalion, AIF. Training included standard basic recruit training, construction of slit trenches and other defensive posts, reconnaissance patrols and dispersal of stores and ammunitions. The men also carried out tactical exercises, defensive patrolling with a sniper, and stalking exercises. The army was pleased, as can be seen from an intelligence report:

These Islanders are a fit, strong looking lot of men. They look fine and savage in uniform. They are as keen as mustard and can give us lessons in drilling and marching. I would rather fight with them than against them. They are very quiet mannered, seem quite content to work all day. If any trouble starts I should like to have a few of the "boys" handy.

In May 1943 the unit became a battalion; the officers, under Major Jock Swain, remained white.

The battalion's activities were varied. The Pioneer Company gave assistance to the 17th Australian Field Company, which was stationed on Horn Island. Knowledge of local reefs and sandbars allowed the battalion to help the 2nd Australian Water Transport Unit, as well as the 22nd Australian Line Section who were laying an underwater cable, linking communications between the mainland, the Torres Strait and New Guinea. A small group volunteered for duty in the 4th Australian Marine Food Supply Platoon, utilizing their knowledge of the surrounding marine life to provide food for the thousands of troops in the area. The battalion's knowledge of the Torres Strait and its waters were invaluable to the Allied effort.

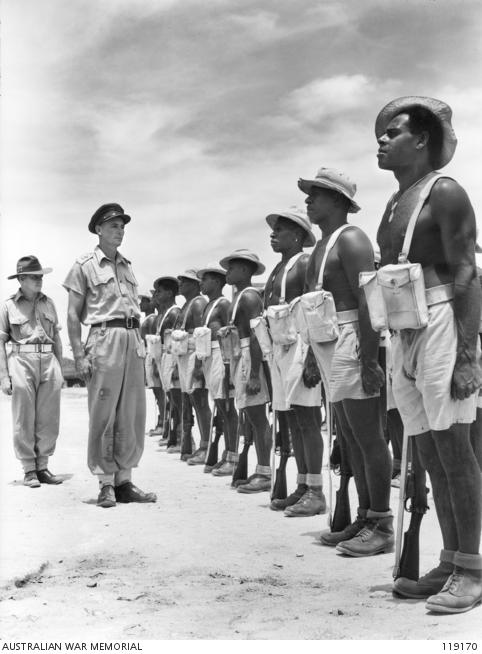

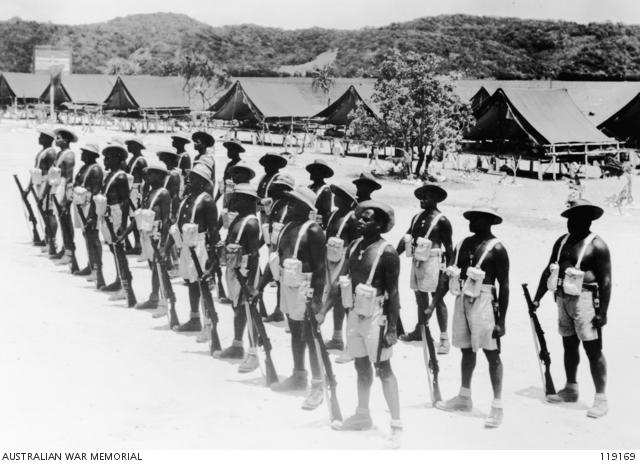

A squad of the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion training in their company lines, Thursday Island, 1945. C47381

From October to December 1943, some members of the battalion had the chance to test out their military skills on a patrol deep into the jungles of Dutch New Guinea. Under a white officer, the group's objective was to explore and report on any connection between the Oba and Wildeman Rivers, and to establish a watching post near the entrance to the Eilanden River. Things went badly when the patrol leader, Wing Commander Donald Thomson, was wounded in a skirmish with New Guineans sympathetic to the Japanese. He was replaced by Captain C.C. Wolfe.

On 17 December, Wolfe and his men set sailed up the Oetoemboewee River onboard the launch, Rosemary. Four days later, they found their first indication that Japanese were in the area. Soon they discovered an old Japanese watching post. Late the next afternoon, while the Rosemary slowly navigated a shallow section of the Ipoekwa River, two 12-metre barges with high bows appeared around the bend ahead. Ten men with rifles manned each barge. They also carried .5-inch machine-guns and mortars.

Wolfe recognized the soldiers as Japanese and yelled for the Rosemary to ram the barges. The skipper misunderstood him Wolfe and reversed the Rosemary. Corporal A. Barbouttis rushed to man the forward machine-gun as a volley of small arms fire broke out from the Japanese barges. The fighting intensified, as the Japanese used their machine-guns and mortars. Barbouttis stood to throw grenades at the Japanese boats and was killed. Six others Australians were wounded. The rest of the patrol were able to extricate themselves and the wounded to safety.

Patrols like this were important to the Torres Strait Islanders, as they were now accepted as soldiers capable of performing more than just labouring tasks. However, they also brought the issue of discriminatory pay scales to a head. Receiving one-third the pay of other Australian soldiers, worried about their families and frustrated at the political situation on the outer islands, the men - who had seen strikes used as a weapon in the pearling industry - decided to strike on 31 December 1943. To the Army, it was mutiny. Two companies refused to work; a third joined initially, but was persuaded that the grievances would be addressed. Eventually the Army agreed to raise the pay to two-thirds of that received by non-indigenous soldiers. Anything higher, it was felt, would cause problems after the war. In the 1980s, indigenous soldiers finally received back pay for their wartime service.

Although issues of discrimination remained, the Second World War gave Torres Strait Islanders and European Australians an unprecedented opportunity to work and serve together. Today many of the white soldiers return to visit the islands where they served in their youth, to smell the frangipani, hear the song "Old TI", sung in island harmony, and most importantly to be reunited with the Torres Strait Island veterans they have not seen for half a century.

Text © the Author