Farewell, once more

In November 2001 Australians farewelled Australian Defence Force personnel deployed as part of the international coalition against terrorism – the crews of HMAS Adelaide and HMAS Kanimbla, and members of the Special Air Service Regiment.

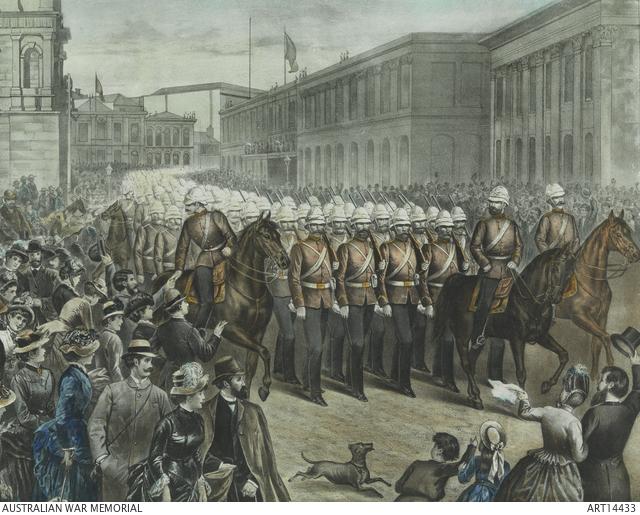

The first time that Australian soldiers left for war was in March 1885 when more than 200,000 people turned out to farewell the 770 men of the red-coated NSW contingent from Circular Quay. The mood was buoyant as men marched off to what one called “a great adventure”. A reporter described the sound of cheering as “like the sound of breaking sea”. Australian colonists had gone to war once before – in 1860, when the Victorian gunboat Victoria had sailed to serve in New Zealand waters during the Anglo-Maori wars, but its departure was quiet compared to the jubilation of 1885. Of course, the hopes of the thousands farewelling the contingent came to nothing. Six men of the contingent died, all of disease, and it returned in June having achieved little beyond demonstrating imperial loyalty.

For the South African War of 1899–1902 the same atmosphere prevailed, except that the departures of the various contingents over two-and-a-half years became progressively less public celebrations. Military ceremonies or parades represented the formal departure, but as men marched to the wharves communities cheered and sang, while private farewells occurred as friends and families called out or rushed into the ranks to offer a hug or a handshake.

New South Wales Lancers parade through Sydney on the day of their departure for the South African War in 1899. C804

The First World War saw more than 324,000 Australians leave for service overseas, 60,000 of whom – one in five – did not return. Again, the first contingents to leave marched past cheering crowds, and were seen off with speeches and bands. The scene recurred at thousands of farewells at hundreds of places – on wharves and on railway platforms, in streets of towns and cities. Bands played as people sang Auld Lang Syne and God Save the King. Gifts were presented – a pipe, a watch, a fountain pen, a wallet: often those gifts came home in the “effects” of men killed at war. Everyone would put on a cheerful face, harbouring but not expressing the fears that all must have felt. Then the train would move off or the ship would steam away from the wharf, and friends and family would be left waving and shouting until their loved ones were out of sight.

A large crowd on the pier at Port Melbourne farewells Australian soldiers departing for the First World War on the troopship Themistocles in December 1914. C332445

In Western Australia, the people of Albany observed the departure of a seven-and-a-half-mile long convoy of ships from the Australian and New Zealand expeditionary forces. Its 20,000 men were not allowed ashore. But many hundreds of them threw messages in small bottles over the side of the vessels, begging the finders to convey words of farewell to loved ones.

As the war wore on farewells became less elaborate, sobered by the casualty lists coming home from Gallipoli and the Western Front. Many of those bereaved in war remembered how the last sight of their loved ones had been at the dockside gates. Long after the war wreaths were laid by mothers wearing black on Anzac Day outside dock gates, and at Woolloomooloo in 1922 a small but haunting memorial was unveiled, inscribed "to commemorate the place of farewell to the soldiers who passed through the gates opposite for the Great War".

Early in the Second World War units of the newly raised Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF) paraded in the state capitals, greeted by vast crowds - more than 500,000 in Melbourne in January 1940. Soon the first troops left for the Middle East. One of the most poignant photographs of the Second World War shows six women - the wives of men of the earliest units of the Second AIF - standing on the wharf at Port Melbourne in December 1939, watching the ship carrying their husbands moving out into Port Phillip Bay.

As a troopship sails in Port Phillip Bay in December 1939 a small group of women wave farewell from the wharf. C22922

For much of the Second World War, though, troop movements were supposed to be secret and were not marked by the traditional formal ceremony. Sometimes, though, news leaked out. The departure of 12,000 men of the 8th Australian Division in a convoy of great ocean liners, which left Sydney Harbour for Singapore in 1941, became a moving testimony of the separation inevitable in war. The official history describes the scene:

Their cheers mingled with those of many thousands of spectators ashore and afloat, the toots of ferries and tugboats, the screams of sirens, and the big bass of the Queen Mary's foghorn as the convoy steamed down the harbour and through the heads.

The heads and foreshores were crowded with well-wishers, many singing the moving Maori farewell - Now is the hour when we must say goodbye. Many waved to men they could not actually see; and many they would never see again, for the majority of this division were captured and one in three - 9000 men - died in battle or as prisoners of the Japanese.

From 1950 Australian troops went to war by air as well as sea. Many of those who joined to fight in Korea 50 years ago had served in the Second World War and their realism contrasts with the naive desire for adventure displayed by their predecessors. A veteran waiting to fly from Mascot told a journalist to "cut the cackle and get on with it". Photographers asked men to wave. "What do you want for six bob a day?" they called back.

The wars in Asia after 1945 were mostly to be fought by small regular forces. Their departures became low-key affairs, witnessed by families and friends rather than half a city. When the 1st Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment left for Vietnam on HMAS Sydney in May 1965 the men were waved away by a few wives and relatives, without even a band.

With the Gulf War, however, sailors and ships were farewelled in ways that resembled the public recognition of earlier decades. The important difference now is that we seem to be more able to acknowledge the apprehension of those left behind. Reports of such occasions show families hugging, and there are tears as well as expressions of good luck.

The Governor-General, Dr Peter Hollingworth, mentioned in his Remembrance Day address to the nation that he had met the servicemen and women leaving to join the international coalition against terrorism. He described them as "professional people, trained for a special task, who nonetheless displayed the same spirit of courage and commitment to country and just cause that links Australians of today with those who have experienced this pain and this pride before."