Tet Turning Point

If there was any one point when the Vietnam War was lost for the allies, the Tet Offensive of 1968 was probably it. Yet the reverse suffered at that time by the southern republic and its American and other allies, including Australia, came in the midst of palpable military success. William Slim had been able to turn “defeat into victory” (the title of his famous memoirs) in Burma in 1944–45; but Tet was a case where defeat came wrapped up in apparent victory.

Soldiers of the 7th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (7RAR), wait for the helicopters that will take them to the starting point for Operation Coburg. C220097

In the last months of 1967 allied intelligence had detected sure signs of communist plans for an offensive timed to coincide with the traditional Buddhist celebrations of the lunar new year (“Tet”) at the end of January. These signs, however, provided no clues about the likely enemy targets and methods, or the nature of what was planned. No one knew that the North Vietnamese leadership, having become no less frustrated than the allies at the apparent military deadlock that had developed in the war, had opted for a massive strike which they hoped might lead to decisive victory.

Although the Viet Cong announced their intention to observe a seven-day ceasefire over the sacred holiday period, South Vietnamese and American commanders were not lulled into lowering their guard. They knew from previous experience that, even though the communists had not usually violated such truces in previous years, they still habitually used any bombing halt or break in operations to re-deploy forces and generally improve their positions.

Accordingly, for the 1968 festival, named that year Tet Mau Than (“The New Year of the Monkey”), the allies decided to respond with a 36-hour ceasefire during which only half the South Vietnamese forces would be permitted to stand-down. American and other forces would be put on full alert and positioned to deal with any attacks the communists might launch. Thanks to the foresight of Lieutenant General Frederick Weyand, the US commander in III Corps Tactical Zone, the focus of defence preparations was specifically altered to cover population centres across South Vietnam, especially the capital Saigon.

For the 1st Australian Task Force (1ATF) this meant deployment outside their usual field of activity in the province of Phuoc Tuy. After the commander of Australian Forces Vietnam, Major General Douglas (“Tim”) Vincent, offered the use of the 1ATF, Weyand asked him to send it to neighbouring Bien Hoa province, to operate alongside American forces preparing to block any thrust against the vast complex of military installations around Bien Hoa city and adjoining Long Binh, located some 25 kilometres north-east of Saigon. The task force move, codenamed “Operation Coburg”, involved the bulk of 2RAR (Royal Australian Regiment)/NZ (ANZAC) and 7RAR, along with supporting armour, artillery and engineers. Left behind in the 1ATF base at Nui Dat would be 3RAR, while a New Zealand company of 2 RAR held the Horseshoe feature.

A group portrait of the members of the assault pioneer platoon, support company, 7RAR shortly before they left on Operation Coburg. C283741

By the afternoon of 24 January the Australian battalions were on the ground in their new area of operations, called “AO Columbus”, on the eastern boundary of Bien Hoa with Long Khanh province. It was an area not totally unknown to Australians, as 1RAR had fought there in November 1965 when it was attached to the US 173d Airborne Brigade (Separate), operating out of Bien Hoa airbase. Almost immediately patrols began having contacts, and these increased over the next four days in both scale and frequency as a number of enemy camps were uncovered and attacked.

At 6 pm on 29 January the truce came into effect, and operations by the Australians were put on hold. During the early hours of the following day, however, some communist forces in the northern half of the country mistakenly began their part in the planned offensive a day early. President Thieu of South Vietnam immediately cancelled the ceasefire and recalled troops on leave to their posts. At 3 am the next day the relative calm was shattered as towns and cities across the nation came under massive attack from the communists.

The extraordinary scene in the north, around the old imperial capital of Hue, was remembered by one member of the Australian Army Training Team (AATTV) who was there with a South Vietnamese platoon carrying out night surveillance on a low hill outside the city. Warrant Officer Terry Egan recounted how, at 3.40 am, the whole horizon from 20 kilometres north of Hue to Phu Bai 15 kilometres to the south-east suddenly erupted to the roar of gunfire. In addition to artillery of varying calibres, flares, mortars and tracer bullets, the night sky was lit by the trails of banks of rockets arcing from the inland mountains towards the city.

A particular focus of the offensive was Saigon, the population of which was sent reeling by an onslaught which was both frightening and staggering in its savagery and destructiveness. Soon large tracts of Cholon, the adjoining Chinese town, were levelled by fighting between communist insurgents and government troops. A notable witness to events in the capital was Major General Arthur MacDonald, who had taken over from Vincent as Commander AFV (Australian Forces Vietnam) only at midnight on 30 January. When he was woken by an explosion near his house in the centre of Saigon a few hours later, he stepped out onto his balcony, in time to see Viet Cong carrying satchel charges on long poles running past towards the nearby Presidential Palace. Not long afterwards, heavy firing broke out down the road, where communist special assault troops also attacked the US Embassy.

Other Australians in the capital had similar experiences. The billets for Australian personnel working in Saigon, known as “Hotel Canberra”, came under attack from about 40 Viet Cong soon after 2.30 am. Members of 7RAR who were providing the guard detachment in sandbag “pillboxes” out in front of the building at the time returned fire, killing one of the attackers and forcing the others to retire. About an hour later, another enemy soldier appeared and fired off a rocket propelled grenade (RPG) before he was also killed. The missile skidded down the road towards the hotel but fortunately did not explode.

Out in AO Columbus the Australians were called upon to deal with a Viet Cong incursion into the village of Trang Bom. D Company of 2RAR supported by armoured personnel carriers became involved in house-to- house fighting to clear the village, only to see the Viet Cong return the next night and cause the whole process to be repeated. Fighting there lasted into 2 February.

Despite the precautions that had been taken at General Weyand’s instigation, the Bien Hoa-Long Binh complex was still heavily attacked by 5 VC Division, resulting in much damage to aircraft, buildings and facilities. The role of the Australians nearby was promptly changed to intercepting and blocking enemy forces as they attempted to move back to their sanctuaries. In the words of the commanding officer of 7RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Eric Smith, for the next few days Viet Cong flowed past his company positions “like water”. For the most part, the enemy were demoralised and disorganised, and avoided contact, although many were caught in platoon ambushes set by the Australians.

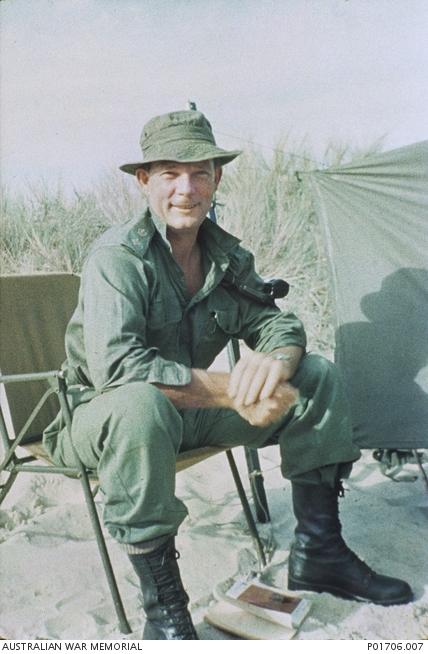

Lieutenant Colonel Eric Smith, commanding officer 7RAR. C257603

One of the most significant actions was that of C Company of 7RAR, which on 5 February found itself in contact with an enemy force in a well-constructed bunker system six kilometres north of Trang Bom. After assaulting the position on three successive days, aided by air strikes, artillery and helicopter gunships, the Australians were finally left in possession of a base camp believed to have been defended by an enemy regimental headquarters and three companies.

After 9 February both battalions were ordered to move back to the south of the area of operations, around two fire support bases codenamed “Harrison” and “Andersen”. From here, 7RAR was relieved by 3RAR on 11 February and 2RAR was returned to Nui Dat two days later. FSB Harrison was now closed, but operations continued to be directed from FSB Andersen, which was located near Trang Bom. Three times between 18 and 28 February, Andersen came under attack but each time the Viet Cong were beaten off.

Meanwhile, the Australians left in Phuoc Tuy were also engaged in heavy fighting, after Viet Cong forces attacked the provincial capital, Ba Ria, and other population centres like Long Dien, Hoa Long and Dat Do. At first light on 1 February the National Liberation Front flag was flying over BA Ria. The whole town appeared to have been infiltrated; government installations had been over-run or cut off, and snipers had taken up position in numerous places, including the town’s cinema and the cathedral.

At Nui Dat, the newly arrived deputy commander of 1ATF, Colonel Donald Dunstan, sent the task force Ready Reaction Force (RRF) to assist the Province Chief in his attempts to recapture the enemy-held parts of BA Ria. A Company of 3RAR, carried in APCs (armoured personnel carriers) of A Squadron, 3 Cavalry Regiment, was ordered to join in the defence of Sector (province) Headquarters. From the moment the carriers entered the town the Australians came under light automatic fire, and by the time they arrived at Sector Headquarters they were receiving RPGs as well. In fighting to secure other government positions, two carriers were damaged and disabled.

By mid-afternoon on 2 February, the majority of the Viet Cong had withdrawn and A Company was relieved to return to Nui Dat. Late the next day, D Company of 3RAR was deployed to Long Dien to assist in clearing it and the nearby village of Ap Long Kien. By early afternoon on 6 February both tasks were complete and the company returned to Nui Dat.

The task force was again called upon on 7 February to assist with the security of BA Ria and (the next day) Long Dien. Other elements of 3RAR were involved in an uneventful sweep of Hoa Long on 8–9 February, but this was effectively the end of the Tet Offensive in Phuoc Tuy. Overall, the casualty toll on both sides had been relatively small – including five Australians killed and nearly 50 Viet Cong.

Operation Coburg was brought to an end on 1 March, and the task force elements returned to Nui Dat. In the fighting in Bien Hoa province, enemy losses had amounted to 145 killed, 110 wounded/escaped and five captured, for Australian casualties of seven men killed in action, three died of wounds, and 75 wounded. The Viet Cong had also lost considerable quantities of weapons, equipment and rice.

If the Australians could count themselves as successful, so could the allies generally across the country. Although initially overwhelmed by the scale of the Tet Offensive, they were able to recover their balance within about six hours of its start. The communists were driven out of most of the towns within four days and the general uprising which they hoped to trigger did not eventuate. Fighting continued in Saigon until mid-February, but the cost to the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army was out of all proportion to the losses they inflicted.

In all, some 45,000 enemy personnel were killed by the end of February (out of a total of 84,000 committed to the offensive), compared to allied military deaths of about 6,000. With the locally based communist infrastructure in the South effectively annihilated, the leadership of North Vietnam would be obliged to send increased numbers of troops from its own territory to keep the war going. Judged on this scale, the offensive had been an unmitigated disaster – in every sense except public perception.

The very fact that the communists had been able to mount such a concerted effort, at a time when allied military authorities had been providing assurances that they were well on top in the conflict, was sufficient for pundits to deduce that the communists must be winning the war after all. It did not matter, for example, that the enemy troops who stormed the US Embassy in Saigon had been on a suicide mission, with all being cut down in the outer grounds. In the sensationalist press, this episode was distorted into a story that the enemy had actually occupied the embassy buildings.

Faced with a tidal wave of public scepticism and disenchantment, the American government accepted a new political and psychological reality. US President Lyndon Johnson rejected requests by his commander in Vietnam, General William Westmoreland, for another 206,000 American troops to regain the initiative and called for a detailed review of official policy in Vietnam. On 31 March, Johnson ordered a halt to the bombing of most of North Vietnam and withdrew from the 1968 presidential election. There could not have been a more stark admission that his policy on the war had failed.

Tet had handed the communists a propaganda coup which actually reversed the military results of the offensive. It was for them, in every sense, a victory snatched from the ashes of defeat.