Reflections on Rwanda

Between April and July 1994 up to 1,000,000 Rwandans died in an orgy of violence unparalleled in the post-war world. It was the culmination of decades of ethnic tension between Rwanda’s majority Hutu population and the minority Tutsis that had erupted into civil war on several occasions, most recently in 1990.

In 1993, a peace agreement was negotiated between the Hutu-dominated Rwandan government and the Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), and the United Nations Assistance Mission to Rwanda (UNAMIR) was sent in to monitor its implementation. Progress toward a broad-based transitional government, however, was slow as both moderate and extremist elements jockeyed for position. On 6 April an aircraft carrying the Rwandan President was shot down, by someone unknown to this day, leading to a complete breakdown in the agreement. The Rwandan Prime Minister and ten Belgian peacekeepers guarding her were murdered. Members of the presidential guard and gangs of Hutu youths began the systematic slaughter of both moderate Hutus, and Tutsis. Enraged, the RPF broke out of the demilitarised zone in northern Rwanda and renewed its military operations. Completely overwhelmed, UNAMIR could do little but watch.

Wary of again becoming embroiled in Africa after the disastrous end to the intervention in Somalia, the international community was slow to act. Some nations, most notably the United States, even advocated a complete UN withdrawal from Rwanda. In the meantime, the killing continued. It was June before the UN Security Council agreed to the reinforcement of UNAMIR and provided it with a more robust mandate to carry out a humanitarian role. While the United Nations slowly marshalled its reinforcements, a French-led interim force tried to establish a humanitarian protection zone in southern Rwanda.

By the time the first contingents of what became known as UNAMIR II began arriving in August it was estimated that more than 500,000 people had been killed, 3,000,000 had been displaced internally, and another 2,000,000 had sought refuge in neighbouring countries. The Rwandan economy had been destroyed, there was little functioning infrastructure, and disease and infection were rife. Having soundly defeated the exgovernment forces, the RPF was now in control and many of its members were bent on retribution.

Lieutenant Colonel Michael Wertheimer examines a malnourished Rwandan child as part of a clinic conducted at the Kibeho displaced persons’ camp.

It was into this chaos that ASC 1 was sent. The Australian government had offered the United Nations a 293-strong medical support force – consisting of a medical company, a logistics company, and an infantry company.

The murder and mayhem of preceding months was readily apparent. Mick Rice recalled arriving at the battered and pockmarked Kigali air terminal to find the walls, the floors, and even the luggage conveyors all covered in blood stains. Decomposing bodies and body parts had to be cleared from the Kigali Central Hospital before ASC 1 could begin operating there, and a routine task for the soldiers was to accompany UN inspection teams and remove and count bodies from the various public buildings in which the genocide victims had unsuccessfully sought refuge – this was done by lining up skulls in rows of ten.

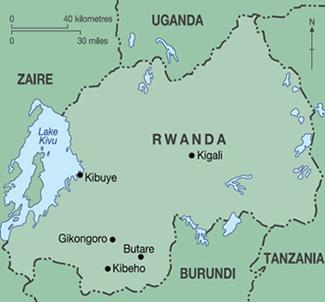

Despite being surrounded by the aftermath of genocide, the contingent’s main business was with the living. The medical company operated a 35-bed hospital in Kigali and a Treatment Section at Butare, three hours to the south-east. Although its primary role was the treatment of UN and NGO personnel, the company also tried to treat locals. Clinics were held in outlying villages and in the sprawling refugee camps.

Robyn Wilkin recalled that it was a challenging environment for the medical personnel. Many of them were used to treating “young, healthy guys with minor injuries and now . . . were looking after anywhere from new-born babies to elderly people with a wide range of diseases and injuries”. Medical specialists, flown in on six week rotations, treated conditions they would never encounter in Australia. Victims of mine explosions, vehicle accidents and gunshot wounds were among those treated and these cases revealed shortcomings in the trauma training of the Australian medical personnel. As a result, greater emphasis is now placed on attaching military medical personnel to civilian hospitals to gain trauma treatment experience.

The UN presence re-established a degree of normality to Kigali and engineers attached to ASC 1 assisted in the destruction of unexploded ordnance and the restoration of civilian infrastructure. The security situation, however, remained tense. Shootings, machete attacks, and rapes continued and the RPF – now the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) – often sought to test the resolve of the UN. On several occasions the Australian soldiers found themselves in tense armed stand-offs with the RPA. It speaks highly of their training and discipline that shots were never fired. Relations with the RPA progressively deteriorated through the end of 1994 and into 1995 as the RPA sought to assert its political dominance, and the random harassment of UN personnel increased.

The efforts of ASC 1’s infantry ensured the medical staff could go about their work unhindered. Although carrying a weapon with live ammunition heightened her awareness of the situation, Robyn cannot remember ever feeling threatened: “I tried not to be scared because I didn’t think it would be tolerable to be scared all the time and I had faith in our troops.”

Despite all that was going on around them, Robyn and Mick Rice found that one of the most difficult aspects of service in Rwanda was repetitive, mundane tasks and long shifts on duty. The nursing officers worked 12 hours on, 12 hours off, while, in some of their sentry posts, the infantry were required to work shifts of two hours on, four off, for a week at a time. It was then, Mick conceded, that their attention and spirits would be prone to slip.

Coping with the wider horror of Rwanda was ultimately a very personal matter. Robyn found that “whilst a lot of things you see are really tragic and sad . . . I think I was able to distance myself. Not everyone can.” Short tempers and a decline in motivation were the main manifestations of stress as the deployment continued, and Robyn was aware of at least one medic being sent home because he was too distressed to keep going. For Mick, a critical part of his role as a platoon sergeant was watching his soldiers, talking to them, doing his best to ensure that no one task was getting the better of them. Often the sheer intensity and necessity of the soldiers’ work gave them little to time to dwell on things, but Mick wonders “how they deal with it nowadays”.

Children feature heavily in the memories of Rwanda – both the best and the worst. Some children toted assault rifles; others bore horrendous wounds with great courage. They were also a beacon of humanity:

Rows of skulls lined up outside a church at Ntarama – one of the few ways UN teams could gauge the true extent of the Rwandan genocide.

The off duty section used to get tasked to go down to the Care Australia orphanage on a Sunday … as much as they used to grumble about having to go out … once they got there they could have been with their own kids.

Returning home in February 1995, the veterans of ASC I shared the experience of many other veterans before them. They were given minimal debriefing and the contingent broke up with little ceremony the day after it returned to Australia. There was now a gap that existed between those who had returned and those who had been left behind. Robyn initially found it difficult to speak of her experiences: “I didn’t really want to talk to them about it, I didn’t know where to start. And I thought they don’t want to hear me talking about Rwanda.” Some felt a sense of professional jealousy directed at them by colleagues who had missed out.

Our two-hour interview was “the longest, by far” that Mick had ever spoken of his time in Rwanda. Returning to the day-to-day routine of unit life was difficult. Mick felt himself fortunate to have been sent off on a specialist course soon after his return, he felt for the soldiers that had to go back to the hum-drum of training; within a year over half of his platoon had left the Army.

Ultimately, Robyn and Mick view their experience in Rwanda in a positive light. Professionally, Mick learnt a great deal, particularly about looking after the welfare of young soldiers, that he subsequently put to good use in a tour of East Timor. The most satisfying aspect of the deployment for him was the way in which his platoon bonded together, worked as a team, and got on with the job. He has occasional nightmares, and the experiences of everyday life can bring back memories of Rwanda, but he thinks the experience has made him more responsive to the world around him and left him with a much more laid-back approach to life.

Rwanda had “an incredibly huge impact” on Robyn’s life. An abiding memory of her time there was of a particular breach birth during which the baby died in particularly distressing circumstances. Leaving the regular army in 1996 she studied midwifery, and then as a result of a “lightning bolt” that struck her while she was working in the refugee camp at Kibeho, she began a medical degree. She is currently completing her internship in the emergency ward of a major public hospital. She still thinks of Rwanda:

It’s always going to be a part of me ... It was all too little too late … but something needed to happen … To me it was a privilege to do it and serve.