Inspirational Bravery

Victoria Cross winners “are linked by a golden thread of extraordinary courage … Beyond this gallant company of brave men there is a multitude who have served their country well in war. Some of them have performed unrecorded deeds of supreme merit for which they have no reward.” – Queen Elizabeth II

Australians have always had heroes and they have often been military men. For a century these were imported: the heroes of Waterloo, Trafalgar and the Charge of the Light Brigade. During this time a handful of local heroes also emerged, such as the explorers and, for some, the bushrangers. It seems that all nations need their own heroes, and villains too.

During the years of 1914–18 a range of home-grown Australian heroes and leaders emerged during what Charles Bean, the official war historian, called “the test of a great war”. These courageous men – and women – were vital to a young and emerging nation seeking its own identity. The school-children’s story of Grace Darling, a young English heroine who rescued sailors in a storm, was supplanted by that of the Gallipoli hero, John Simpson, rescuing the wounded with his small donkey.

When Australians first went into battle in 1915 the home newspapers wrote with enthusiasm about the bravery of the Anzacs. But the public still sought special individuals. Alongside Simpson, early Gallipoli heroes a proud nation embraced included Major General Sir William Bridges and Corporal Albert Jacka. Bridges commanded the 1st Australian Division at the landing on 25 April 1915. He was killed a few weeks later by a Turkish sniper’s bullet. In a unique salute, the general’s body was brought back to Australia for burial, the only Australian body brought home during the war. Albert Jacka was the first in the AIF to receive the Victoria Cross.

Captain Albert Jacka, VC MC and Bar, in 1917. C376048

Overall there were about 15,000 bravery medals given to members of the AIF, of which the Victoria Cross was the highest, while the Military Medal was the most familiar. Lieutenant William Carne, historian of the 6th MG Company, observed, “[There] appeared to be an Army practice of awarding few decorations for an unsuccessful operation and granting generously for a successful one.” Generally, it seems high awards were mostly given for contributing to, and inspiring others towards, success.

During the war the most usual decorations given – the Distinguished Service Order, Military Cross, Distinguished Conduct Medal and the Military Medal – could not be awarded posthumously. Those killed performing a brave deed mostly went unrecognised.

It is often imagined that rescuing wounded or saving lives is a standard criteria for bravery decorations. However, Colonel A.G. Butler, the official historian of the Australian Army Medical Services in the war, made the point that high awards for such actions were not normal.

George Mersey Hammond, MC, MM, in May 1918. One month later Hammond died of wounds back on the Somme. C204160

Sergeant Claud Castleton was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross on one of the few times in the war that it was given for rescuing wounded. C1497

Heroes are special, and men like these are few. Lord Moran, in his study of men in war, The anatomy of courage, drawn from his own First World War experiences as a British army medical officer, said; “I can find little … to support the comfortable creed that all men are heroes. A few men had the stuff of leadership in them; they were like rafts to which all of the rest of humanity clung for support and for hope.” Moran looked closely at fear, courage and cowardice.

Courage and fear are not separate subjects, although the latter is not so often written about. During battle, fear was a natural human response and was ever present among front-line troops, including the bravest of them. It existed in different forms and degrees. As Moran said, “Fear, even when morbid, is not cowardice.”

The ordeal of heavy battle was a most severe test. In it, “the mask we wear through life drops off,” said Moran. An Australian, Captain George Mitchell, said the same thing this way: “In battle … the soul of every participant is laid bare for all to see. Battle strips all masks and shams from every one, each having to stand naked to the gaze of his companions.”

Fear experienced during combat was something Mitchell was prepared to talk about. This officer had won the Distinguished Conduct Medal at Bullecourt in 1917, and the Military Cross in March 1918. In the latter action it was reported that he led his platoon in “an absolutely fearless manner”. Still, he wrote about the need to deal with fear when he addressed young officers of a new war in 1940. “Fear,” he said, “grips you everywhere; constricting your throat, squeezing your heart. It is like a lump of ice in your stomach. Then panic surges over you and you are ready to run – run anywhere.”

The fury of battle affected men in different ways. “In battle,” said Mitchell, “you will find men firing with sights set wrong. You will find men, stunned by impact of battle, aiming and snapping empty rifles. You will find men affected by the sight of the dead and wounded round them. You will find men in the grip of fear cowering in dugouts, men without fear exposing themselves recklessly. You will find men carrying on who should be in hospital, you will find malingerers ‘swinging the lead’, trying to get into hospital.”

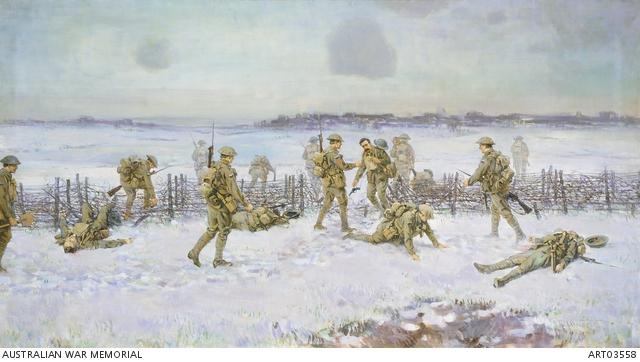

Charles Wheeler, Bullecourt battlefield. C177650

It was Lord Moran’s belief that in battle all normal men felt fear, and most carried on despite it. Some even found exhilaration in action, but still, “no man has an unlimited stock of courage”. Extreme ordeals and long exposure to combat could have an accumulative effect. In one case, an Australian Victoria Cross winner of 1916 was charged with desertion the following year; he was sentenced to two years hard labour, although this was suspended.

The strain of battle even affected great heroes such as Arthur Maxwell, Harry Murray and Albert Jacka. Maxwell, who had been decorated for bravery at Mouquet Farm and Messines, told Charles Bean that at one point in 1917 after a mate was killed, “I went quite off the handle. When I got back … I couldn't speak without crying – broke up like a baby altogether.” Harry Murray was a VC holder and the most decorated officer in the AIF. He said: “You know, with me it has come to this. I have to go up the line myself now, so that they do not see me duck the shells.”

Jacka’s breakdown came after he was awfully wounded at Pozières where he had led a small group of men in a counter-attack. In the action Jacka was shot a number of times, each time he was knocked to the ground, and still he threw himself with rifle and bayonet against the enemy, inspiring all those around him. At times during his long recovery he experienced “physical shaking that would continue for hours at a stretch”. Still, after a rest, this remarkable man would later earn another Military Cross to add to that awarded for the Pozières action.

Training and discipline helped in mastering fear. Experience in battle also helped, although at its extreme it could result in war weariness and this would have its own serious affect on morale as the AIF found by 1918. There were other positive factors too, like good leadership and mateship; in battle men drew strength from each other. At such times cool control and example were invaluable. Rest was also vital for troops before and after action. This was noted by Charles Bean. “Most troops, so long as they were well rested”, he said, referring to the Australians, “preferred an offensive role to the wearing, endless hardship suffered, for example, by the German trench divisions.”

Hope could feed fear. In this war the loss of life among front-line troops was immense, and soldiers were always confronted by their mortality. Many were fatalistic. Mitchell’s advice had been to: “Throw overboard all faraway things you hold so dear – the thought of some girl, your civil life ambitions, all thoughts of gain. Those things are bridges with the past, a past which is far beyond your reach. But they are bridges over which fear can and will travel all too easily.” Little wonder then that men who had done this greeted the news of the armistice when it came in 1918 with as much bewilderment as celebration.

Among those acknowledged as heroes were some who would motivate others and spur them on; they could even affect the course of an action. There are repeated examples in the Australian citations for bravery awards where some officer or another soldier provided inspiration or leadership to their group. Inspirational soldiers were always held in high esteem within their units for these men gave the leadership that others were seeking. At least a dozen Victoria Cross citations refer to the hero’s ability to inspire others.

For example, Corporal “Snowy” Howell fought a one-man action in holding off the enemy with bombs and bayonet until he was severely wounded at Bullecourt on 6 May 1917. His action “was witnessed by the whole battalion and greatly inspired them in the subsequent successful counter-attack”.

Corporal George “Snowy” Howell receives his Victoria Cross and Military Medal from King George V on 21 July 1917. C376067

There was also Sergeant William Ruthven who fought at Ville-sur-Ancre on 19 May 1918. There, when most of the officers became casualties, he virtually took command of his company. During the advance, he single-handedly attacked enemy posts. His citation read, “Throughout the whole operation he showed the most magnificent courage and determination, inspiring everyone by his fine fighting spirit, his remarkable courage, and his dashing action.”

Not all the notable heroes of the AIF were VC holders. Lieutenant Colonel Norman Marshall, who had joined up as a private, received the Distinguished Service Order on three occasions, as well as the Military Cross. Typically, at Villers- Bretonneux in 1918, “with total disregard of danger he passed up and down not only his own lines but the lines of the other battalion encouraging all ranks by his confident bearing, voice and action”. This officer inspired “the courage and determination of his men”. In a tight corner, wrote Charles Bean, “The mere knowledge that Norman Marshall was in charge would give confidence to all Australians who were aware of the fact.”

Australians still remember their war heroes. But the great heroes thrown up by the First World War, men such as the VC winners, Jacka, Murray, Cherry, and others, together with the multiple award winners like Black, Maxwell, Norman Marshall, and George Hammond are no longer household names. New names were added to the roll of heroes during the Second World War, and later. Today alongside the enduring story of Simpson and his donkey, many may recall Sister Vivian Bullwinkel, who survived a massacre and years as a prisoner of war, and “Weary” Dunlop, the famous prisoner-of-war doctor.

The original grave of Captain Percy Cherry, VC, MC, at Lagnicourt, France. “His leadership, coolness and bravery set a wonderful example to his men … Wounded … he refused to leave his post and there remaining, encouraging all to hold out at all costs, until this very gallant officer was killed.”

C1029098

It seems that those now best remembered from the wars are mostly from among the non-combatants. Perhaps today we look past the fighting soldiers for the type of qualities and inspiration that are needed in peacetime. Consequently we risk forgetting what the front-line soldiers had to overcome and endure and how among them there were those who could step forward and provide leadership, comfort and inspiration even just to carry on, in the most bloody and demanding battles of the Great War.