Kashmir Inc.

A dispute in your local neighbourhood can be awful. Tension in the street, bickering over the back fence, grumpy letters slipped into the letterbox late at night. Occasionally, the strain becomes so bad that someone trots off to get a lawyer’s advice.

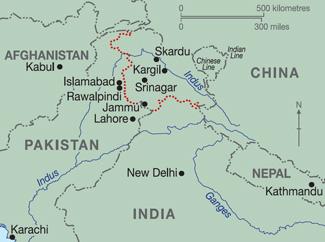

So just imagine the extra difficulties that arise when two entire countries fall out. Consider, for instance, the cosmic array of problems that exist between India and Pakistan in their long-running dispute over who should control the territory of Kashmir. For nearly 60 years this stubborn conflict has defied all attempts at resolution. India claims the northern province for itself. Pakistan regards the land as stolen property. Wars have erupted, riots have ensued.

The international community has embarked on many different strategies in an effort to end the conflict. The United Nations sought to keep the peace by posting military observers along a fragile cease-fire line – a mission Australian soldiers served in over many years from the early 1950s. Australia also provided the services of an eminent jurist, Sir Owen Dixon, to mediate between the two countries. On a few occasions, the British Commonwealth even flirted with the idea of sending a brigade to police the troubled region. Yet despite all these efforts, few have boasted much success.

Could the path to peace be more straightforward? Is there a simple answer to this complex and apparently endless quarrel? An enterprising Sydney lawyer named Brian Molloy certainly thought so.

“It is wrong to think,” he declared, “that international problems between States are more difficult of solution than those between man and his neighbour.” Ordinary people need to grapple with serious problems every day. They are hampered by the same irrational human emotions that afflict even prime ministers and presidents.

In these situations, solving the problem often requires the independent perspective of an outsider, a detached person who is able to see the issue clearly so that a fresh approach can be made. And following such logic, this self-described “run-of-the-mill lawyer” from Australia applied himself to the intractable international dispute over Kashmir.

“I make so bold as to claim that I have solved it,” Molloy confidently announced to a 1967 gathering of the World Peace Through Law Center in Geneva. “I believe my solution is one acceptable to both parties and beneficial to both and to the local inhabitants and one which will for all time remove this area from one of conflict to one of peace and prosperity.”

The dangers of keeping the peace in Kashmir. This jeep collided with an oncoming lorry in 1981, injuring one of the two Australian passengers, Captain Bill Reid.

His proposal was seductive, at once both straightforward and original. Kashmir is no economic prize, Molloy said, rich in neither mineral resources nor production nor population. But “Kashmir” is a lovely name known all over the world, thanks to its sparkling diamond blue lakes, moist yellow valleys, and soaring emerald green mountains. This spectacular setting would be the ideal site for a multi-storeyed tourist resort, one bound to make a fortune.

Molloy wanted both countries to surrender their territorial claims. Instead of fighting about ownership, India and Pakistan would establish a joint corporation to administer and develop the tourist potential of the region – “The Kashmir Company Limited”. They would make money instead of war.

He spelt out his idea of how this new authority in Kashmir might operate. As a private company, Kashmir would be governed by a board of directors, the membership comprising an equal representation from both India and Pakistan. An independent chairman would be drafted, preferably a person of international renown and unimpeachable stature, definitely not someone beholden to either of the disagreeing countries.

The composition of the board would also give new meaning to the modern phenomenon of “shareholder democracy” – the local inhabitants of Kashmir would get to elect an agreed number of representatives. Should a dispute arise regarding the Company’s administration of Kashmir, an independent Supreme Court would settle it. Recourse to this process was open to any director, any citizen of Kashmir or either government in Islamabad or New Delhi. The Company would be bound to obey the Court’s directive.

The Company would pay India a nominal rental based on a 99-year lease. Both countries would grant an initial cash subsidy to help develop the region’s tourist infrastructure. New hotels and roads would be especially needed, along with money for international marketing. After a time, the Company would become self-sufficient, meeting its own development expenses associated with further tourism and addressing the needs of the local population. Any profits generated were to be divided equally between India and Pakistan.

“Here is a liability turned into a boundless asset at a low cost,” predicted Molloy. “A scheme which involves no loss of prestige or of status but benefits every citizen of both parties and the treasuries of both governments. What more can you want? What more can you expect?”

This radical proposal to privatise a wasting international dispute soon became more than just idle conjecture at some far away symposium. Taking the initiative, Molloy sent the details of his scheme to colleagues in India and Pakistan, hoping to find support. In October 1967 he also forwarded a copy to the Australian Attorney-General. He heard that Indira Gandhi, the formidable Indian Prime Minister, had accepted an invitation to visit Australia early the following year. Given the opportunity to discuss his proposal in person, Molloy was convinced that he could “enlist her” among his supporters.

The Attorney-General passed the request along to the Prime Minister, who read Molloy’s proposal with interest but declined to facilitate a meeting. Molloy failed to penetrate Mrs Gandhi’s retinue. In fact, when she eventually met with the Australian Cabinet in May 1968 the subject of Kashmir was discussed only in the most general terms, before they turned to the pressing question of Australian assistance for India in the field of animal husbandry.

Paul Hasluck, Minister for External Affairs,(right) in Vietnam in 1967, around the time he became intrigued with Molloy’s proposal. His bureaucrats were less impressed.

Molloy remained convinced that his bid to establish Kashmir Inc. had merit. Later that year a friend in the business community took up the campaign. Thanks to this connection, the details of Molloy’s plan found their way in a personal letter to the desk of Paul Hasluck, then Australia’s Minister for External Affairs. Intrigued, Hasluck passed the proposal along to his department for comment.

The bureaucrats’ response was blunt: “Mr Molloy’s approach to the Kashmir problem seems to us to ignore the political realities.” India still claimed the territory entirely for itself, while Pakistan continued to resent India’s presence in Kashmir. An earlier draft of the briefing note for the minister was even less kind, dismissing the “facile formulae” put forward in the Molloy plan.

The foreign policy managers in Canberra worried that to entertain the proposal seriously would risk Australia’s policy of “careful neutrality”. Kashmir was a delicate argument between two fellow members of the Commonwealth. Any negotiations about the status of the territory would favour Pakistan – acting to preserve the status quo favoured India. Better then for Australia’s official attitude to remain strictly ambiguous.

Hasluck was persuaded that the issue of Kashmir aroused intense political and religious feelings, emotions not easily discarded. Ultimately, he disagreed with Molloy’s principal contention that international political problems are no more serious than those between a man and his neighbour.

Today, Kashmir remains an incurable sore in relations between two of the world’s most populous neighbours, India and Pakistan. When Molloy first turned his attention to the problem, almost 20 years of conflict had preceded his proposal for a tourism-inspired recovery. An even wilder scheme might be needed now.

A disputed land

Control over the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir (commonly known as Kashmir) has remained a source of tension between India and Pakistan since partition and independence in 1947.

The Hindu Maharajah of a nominally independent and Muslim-dominated Kashmir turned to India for military assistance in crushing a local rebellion. India agreed on the condition that the territory became a part of the Indian state. Pakistan opposed India’s incorporation of Kashmir and by mid- 1948, the two countries were at war.

Sir Owen Dixon in 1942. After the war, Dixon attempted to mediate between India and Pakistan over the issue of Kashmir.

A few months later, a peace deal left Kashmir a divided land, its future status uncertain. The United Nations posted an international group of military observers along the ceasefire line in an effort keep the two countries from resuming hostilities while simultaneously making further attempts to reach a final agreement. Sir Owen Dixon, a Justice of the Australian High Court, was appointed as a UN special envoy to mediate the conflict. Although Dixon was unable to negotiate a settlement, Australia’s involvement in the conflict did not end.

Major General Robert Nimmo, a Gallipoli veteran who had also served during the Second World War, took up command of the UN military observer group in 1951. Eight other Australia soldiers soon joined him in this multinational force, usually staying for a one-year tour of duty, although many chose to extend their time in Kashmir. Nimmo himself served on the border for the next 15 years, reporting on many skirmishes between the two sides and another full-scale war in 1965. He died of natural causes in early 1966.

Australia continued to send soldiers to act as observers in Kashmir, increasing its commitment during the 1970s to include a RAAF Caribou aircraft and crew. But by 1985, Australia felt that its contribution had been enough and withdrew from the UN mission in Kashmir. Around 150 Australians had served with the UN mission over 35 years.

UN observers remain in the territory and there is still no final settlement on the status of Kashmir. The conflict returned to international prominence on 8 October 2005 when a devastating earthquake hit the area and resulted in many thousands of casualties. Sensing hope amid the rubble, optimistic observers predicted a fresh trust between India and Pakistan while both countries cooperated to deliver humanitarian assistance to the battered region. Australia also returned to help, sending a defence force team that included transport aircraft along with medical and communications personnel.

Further reading

Brian Molloy’s original proposal is published in the proceedings of the World Peace Through Law Geneva World Conference 1967 (Geneva: World Peace Through Law Center, 1969), pp. 106–09

See also: Peter Londey (2004) Other people’s wars: a history of Australian peacekeeping

Text © the Author