The last to fall

By the end of October 1918, the First World War was over for most Australians. Sadly, for those few still fighting, the war’s final days could still prove deadly.

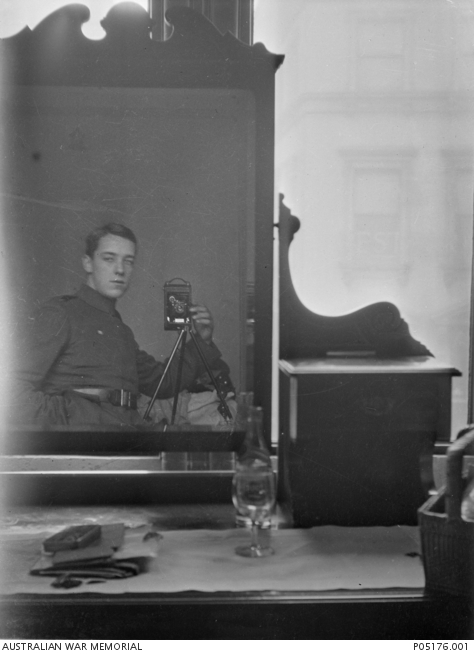

Members of No.4 Section, 1st Australian Tunnelling Company, Wallonie, Belgium, 8 February 1919

The war was drawing to a close. Corporal Albert Davey was a 34-year-old ex-miner from Ballarat. A married man, he had left Australia two years earlier as a member of the 1st Australian Tunnelling Company. By late 1918, with the armies moving quickly over open country, there was little underground activity on the Western Front and Davey and the other tunnellers found themselves being used on general engineering, roadworks, bridging and labouring jobs.

Throughout October 1918, with the Somme battlefields and the Hindenburg Line behind them, the British Fourth Army continued to advance eastward, pressing hard on the heels of the retreating Germans. At this time there were about 100,000 Australians serving on the Western Front. Most of them were in the five divisions of the Australian Corps under Lieutenant General Sir John Monash. These divisions had fought their way to the Hindenburg Line and three of them had taken part in the breakthrough or in the attacks on the line’s reserve system a few days later. Their last action had been the capture of Montbrehain on 5 October. Now they were resting. The divisions had been withdrawn to recover, altough much of their artillery continued to support the advancing American and Britsh corps for another month.

But there was no rest for the tunnellers. They were army troops and were available for use whenever the British should need them. They sometimes found themselves alongside their countrymen, and in the previous months they had been attached to the Australian Corps. Now they were with the British IX Corps/ The 1st Tunnelling Company was probably the best known for its work in mid-1917 when its men dug under the German lines at Hill 60 in Belgium and denoted huge mines, blowing the enemy sky-high during the battle of Messines. After the war the unit erected a permanent memorial in those cratered fields and it is still there today.

An Australian artillery battery preparing to move in support of the Fourth Army's advance in October 1918. Australian gunners supported the attack on the Sambre Canal.

Throughtout October the enemy continued to fall back. The Germans may have been a beaten force but they were still capable of inflicting heavy casualties and the oncoming wet and cold weather was threatening to slow or stop British progress. On 1 November Captain Oliver Holmes Woodward, commander of 1st Australian Tunnelling Company, received the news that No. 4 Section of his company would be attached to a field company of the Royal Engineers in support of an attack by the British 1st Division across the Sambre–Oise Canal. This was to be part of a major battle to be launched on a wide frontage in only a few days.

Woodward, a former mining engineer, was a brave and intelligent man and had already been awarded the Military Cross and Bar. The second award was for his recent courageous work during the British Fourth Army’s advance when the Australians, Americans and British, fighting side-by-side, broke through the German Hindenburg Line. After the war he would have a distinguished civil mining career and become General Manager of North Broken Hill Ltd.

In the weeks leading up to this battle the army’s advance had taken it beyond Le Cateau – remembered as the site of a stand by the British in 1914 during their retreat from Mons – and up to the Sambre canal. This waterway was not as formidable as the St Quentin canal that the Germans had incorporated into their Hindenburg Line; still, no crossing would be possible without heavy fighting and further casualties.

The canal facing the British was a significant obstacle for the advancing infantry and the accompanying tanks and guns. It provided the Germans with the opportunity to make a solid stand. Woodward later said: “No. 4 Section probably had to thank me for their task as my course of training at the bridging school most likely governed my selection.” The Australians’ role was to unload and assemble heavy steel joists during the night and bring them and other material up to the canal. Later, and once the infantry had established a bridgehead, they were to construct a heavy-duty bridge near a lock suitable for tanks to cross. It would all have to be done under enemy fire.

On the morning of 3 November, a Sunday, as the tunnellers prepared to move up closer to the front line in preparation for the attack, Corporal Albert Davey went to Woodward and said he was convinced he was about to die. Woodward regarded the man as one of his best non-commissioned officers and was surprised when he was asked to take care of Davey’s personal belongings and promise to send them to his wife if anything should happen to him. Davey must have seen that the war might soon be over and felt that going into one more heavy battle was chancing his hand too far.

Woodward spoke to him firmly and told him not to be foolish.

Zero hour for the attack was set for 5.45 am on 4 November. From that moment the ground shook from the massed artillery fire falling on the opposing positions. Australian gunners contributed to this artillery barrage. Davey was killed by enemy shelling while waiting for the order to move forward. Woodward later recalled that he went ahead at 6 am, “just in time to see Major Findlay of the 409th Field Company [Royal Engineers] lead his men across the lock”.

Major George Findlay, a Scot with whom the Australians were operating, led bridging and assault parties. His men were to bring forward improvised light bridges to throw across the waterway to allow the infantry to cross. They were met with heavy enemy shelling and machine-gun fire. Findlay urged men forward only to have them repeatedly shot down; he too was wounded. Still, this brave officer repaired a vital bridge and got it into position. He took his men over the bridge and the infantry followed. For his actions that morning he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Woodward was decorated for his work that day too. Once again he received the Military Cross; remarkably, it was his third such award. The recommendation read:

His section was entrusted with the construction of a heavy bridge to carry tanks. The successful completion of this work done within 5 hours … was mainly due to his detailed preparations made at very short notice, and his example and disregard of danger under intense artillery and machine-gun fire.

Officers of the 1st Australian Tunnelling Company, AIF, following the battle of Messines, Belgium, 1917. Woodward is seated front left.

The British attack inflicted a decisive blow. The Germans retreated and in the following week only the cavalry could keep up with them. The Australian divisions, having had a period of recovery, began to move towards the battle front. On 10 November, beyond Le Cateau, the 1st and 4th Divisions began relieving some of the tired British troops who had fought across the canal. However, they would not have to go into action again: next day the news quickly spread that the war was over. The Germans had signed an armistice.

Sadly, Corporal Davy’s premonition had proved correct. He had been killed as the battle opened, as had two other Australians, Sappers Arthur Johnson and Charles Barrett. The three Australians were buried in a row, together with about 50 other British soldiers, in the military extension of the local cemetery not far away at the village of Le Rejet-de-Beaulieu. The padre from Captain Findlay’s company conducted a service.

The death in battle of three diggers of the tunnelling company so close to the end of the war was tragic. They seem to have been the last Australian fatalities in a ground action on the Western Front. On the same day, further north, three pilots of the Australian Flying Corps were killed in air combat.

These few men made the same sacrifice as tens of thousands of others during the war, yet their deaths seem all the more poignant because they died only a week before the war ended and when very few Australians were still in action. For the three tunnellers, it had been their misfortune to be serving apart from the main body of the Australian Corps and to be used in the Fourth Army’s final battle.

Other Australians died away from the battle front. There were many in hospitals in France, Britain, the Middle East, Australia and other places who would succumb to wounds received earlier. Sickness and disease could also be as deadly as the enemy’s bullets. The last Australian battle deaths on the Western Front may have occurred on 4 November 1918. However there were more deaths in the following days, including about 20 from illness and wounds on the last day of the war.

Many thousands more would die of war-related causes in the decades to follow.

Cite as: Burness, Peter, “The last to fall”, Wartime 44 (2008) 38–41

A bad day for the Australian Flying Corps

4 November 1918 While German ground forces retreated on the Western Front in the closing weeks of the war, their air force continued to fight hard. The first few days of November were stormy and wet, but on 4 November the weather was clear and the scene was set for some of the last great air battles of the war. These fierce encounters east of Tournai resulted in the loss of five Snipe aircraft from No. 4 Squadron, AFC, and the deaths of three pilots.

Mid-morning, a patrolling Snipe formation spotted a larger group of Fokker D.VIIs. Joining with some nearby British fighters, the Australians climbed and then attacked. Two Snipes did not return, although both pilots survived to become prisoners.

Worse was to come. That afternoon No. 4 Squadron pilots flew a joint raid with SE5a fighters of No. 2 Squadron, AFC, and DH9 bombers of the Royal Air Force. As the formation turned for home, a dozen Fokkers were seen closing in. The Snipes climbed and then plunged into a swirling dog-fight. Some German aircraft were claimed by the Australians, but three of their own were missing. Captain Thomas Baker and Lieutenants Parker Whitley Symons and Arthur John Palliser had all been shot down and their deaths were later confirmed. Both Palliser and Baker were aces.

Recent research indicates that their opponents that day were from Jagdstaffel 2 “Boelcke” and that Symons was probably a victim of Leutnant Ernst Bormann. Other claims were made by Rittmeister Karl Bolle, the staffel commander.

John White