The Japanese experience at Buna-Gona

Exhausted and starving, the men of the 144th Infantry Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel Tsukamoto Hatsuo, reached south Giruwa, Papua, early on 17 November 1942. After fighting along the Kokoda Trail for almost three months (four months for some members of the advance party of the South Seas Force), they no longer looked like the men of the glorious Japanese Imperial Army, but more like a horde of beggars. Tsukamoto’s troops immediately constructed a base in south Giruwa to prepare for defence against the pursuing Australian force. At this time the Japanese were occupying the beachheads in Basabua (as the Japanese called this area), Buna, and Giruwa.

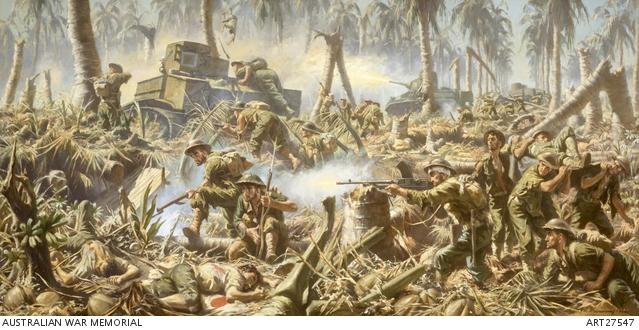

Australian action at Buna, Mainwaring, Geoffrey 1962. ART27547

The first major battle occurred only three days after Tsukamoto’s arrival in south Giruwa. On 20 November the Australian force made a daring charge. This attack was a surprise to the unprepared Japanese. The Australians penetrated the position of the 3rd Battalion of the 144th Regiment and came close to the regiment’s headquarters, where the regimental colour was placed. The Japanese frantically fired rifles and machine-guns, but the enemy advanced to within several metres of the colour. Losing the regimental colour, which had been presented to the regimental commander by the Emperor, would have been the worst humiliation for the regiment. Tsukamoto urgently ordered the colour bearer to burn the flag. Fire was set to the flag, but it had absorbed moisture during the march in the jungle and did not burn quickly. Meanwhile, the enemy finally retreated; thus the flag, though partially charred, was saved. A young medical officer, Lieutenant Yanagizawa Gen’ichirō, witnessed the flag guard officer desperately trying to burn the flag. To Yanagizawa this chaotic fighting looked like an infantry regiment’s desperate last stand and he felt it was futile. The frantic battle left thirty Japanese men dead, including the 3rd Battalion’s commander.

The Australians tried to penetrate the Japanese position several times later without success. Around 25November, to reduce their casualties, the Australians changed their tactics; after intensive aerial bombing and bombardment of the Japanese position, the infantrymen advanced, firing, but they retreated when the Japanese shot back. The enemy repeated this pattern each morning and afternoon. Thus, the south Giruwa front became relatively calm. The men in the garrison could safely do everyday chores, such as cooking and using the latrine, between the enemy’s attacks.

Around the end of November, the Australians changed their focus from Giruwa to Basabua. Basabua was the weakest beachhead, defended by the road construction unit of 700 to 800 men led by Major Yamamoto Tsuneichi; of these, the majority were members of the Takasago Volunteers, a unit of native Taiwanese labourers. They had been reinforced by about seventy men from the 41st Infantry Regiment and eighty men from the South Seas Force, who were the only real fighting force. Allied forces had been attacking the Basabua garrison with intensive aerial bombing and artillery bombardments, which transformed the palm forest into a barren landscape with many large holes and a few palm trunks sticking up without leaves. However, the bombing and shelling were not as effective as the Australians hoped, unless men in the trenches and foxholes (known as takotsubo or octopus trap) were directly hit.

Fall of Gona, Japanese captured in the final assault on Gona. December 1942

On the evening of 28 November, the Australians attacked the garrison for the first time, but they were repelled by the counter-attack from Japanese hidden in the foxholes. The Australians repeated these attack-and-retreat tactics after bombing and bombardment. They too suffered heavy casualties, but the number of Japanese dead was increasing. The garrison was by then in an open landscape, which restricted the movements of the defenders: they had to stay in waterlogged foxholes most of the time; they could no longer bury their dead comrades; and starvation was creeping in. To help their dire situation, on the night of the 30th a rescue party on two barges led by Major Koiwai Mitsuo, the commander of the 2nd Battalion, 41st Infantry Regiment, was sent to Basabua from Giruwa. Koiwai tried to signal the garrison with a flashlight but received no reply; when the enemy opened up with machine-gun fire, he had to fall back. On 1 December, once again the men in the garrison repelled the attackers, but their wireless was destroyed. The Basabua garrison was now completely isolated. They were still fighting with determination, even using the bodies of their dead comrades as cover, but destruction was only a matter of time.

Major Yamamoto felt that defending the small garrison under siege was futile, but unauthorised withdrawal was a serious offence. After agonising alone, on the night of 8 December he assembled about 100 men and ordered them to withdraw, but he himself decided to stay. It was too late for a large-scale withdrawal. Only small groups of men escaped through the jungle and by sea. A close combat ensued the next morning before the garrison was conquered. An unbearable stench was permeating the battleground filled with hundreds of dead bodies.

Lieutenant Maegaki Juzō from the 41st Regiment was one of a dozen survivors from Basabua. When Maegaki went to report to Colonel Yazawa Kiyomi, the regiment’s commander, Yazawa was furious, yelling: “You fled! How could you come back shamelessly?” Maegaki, who had been wounded in the hellish battle and knew the mental agony of Major Yamamoto, talked back: “I came back through the enemy to report the last phase of the battle. I am ready to die if you order me to die.” After listening to the report, Yazawa understood and called a medical officer to look after Maegaki’s wound immediately.

Buna was the next garrison to fall to the Australians and Americans. Buna Garrison, which covered a five-kilometre stretch of coastal land with two airfields, was defended by the 5th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Party (290 men) and the 5th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Party (110 men) and two airfield construction units (280 men) led by Captain Yasuda Yoshitatsu. Yasuda was the most experienced land-combat specialist in the Imperial Navy; his nickname was “Army Colonel Yasuda”. Since early September, Buna had been under Allied aerial attacks, which made the airfields unusable. The American force landed on the beach in Oro Bay south-east of Buna on 16 November. With superior air and fire-power, the Americans expected to overcome Japanese resistance within a short time, but they underestimated Japanese strength and resolution. On the morning of 19 November, the American land force started its first major offensive. However, the timely Japanese reinforcement of about 700 army troops (3rd Battalion of the 229th Infantry Regiment and the 2nd Company from the 38th Mountain Gun Regiment) led by Colonel Yamamoto Shigemi had arrived in Buna one day earlier and taken their designated positions to prepare for the attack. Leaving old service rivalry aside, the navy and army personnel coordinated well. The Japanese defenders withstood the first attack and the ensuing attacks. During the early battles, Japanese air units also supported the land force. For the first two weeks the American attacks all failed, and the GIs were utterly exhausted from fighting in the swampy jungle. On 30 November, frustrated with the failure of the offensive, General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the South-West Pacific Area, appointed Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger as the new American commander of the campaign, and famously told him, “I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive.”

While the Allies continued to build up their military power in the beachhead area, there was no prospect of supplies or reinforcement for the Japanese. On the morning of 5 December, the Americans attacked the eastern section of the garrison with five armoured vehicles, but the Japanese defenders destroyed the vehicles within a short time using grenades, magnetic mines, and anti-tank guns, dispelling the attackers before nightfall. However, the Americans succeeded in penetrating the western section, isolating the Japanese troops in Buna village. The next day Yasuda ordered all important documents be burned. In the eastern section on 9 December intensive bombardment of over 2,000 rounds destroyed the main position of the naval troops west of the new airfield, leaving many of them buried alive. In the western section, Buna village fell on the 14th after the defenders withstood a dozen enemy attacks. On the 18th Australian forces joined the Americans with M3 light tanks on the western section. The Japanese defenders, hiding in foxholes and trenches during the intense aerial bombing and mortar shelling, noticed the approaching tanks too late. This attack reduced the 400 army troops there to 60 and forced the remaining army and navy troops to retreat. The Allied force continued to attack with tanks. The defenders fought desperately, even using anti-aircraft guns against the tanks, but they were confined to an area only several hundred metres wide and 200 metres deep. Destruction was drawing near. On the 27th both the Imperial Navy and the Army ordered their respective forces to retreat to Giruwa, but it was too late for systematic withdrawal with many sick and wounded men. Yasuda decided to stay and fight and sent a farewell telegram next day. During the last phase of the battle, similar scenes to those in Basabua were repeated. The men lived in their foxholes or trenches. They could not bury the bodies of dead comrades around them, and some slept next to decaying bodies. Buna fell on 2 January 1943.

Giruwa was the last garrison after Buna fell. When Tsukamoto’s 144th Regiment occupied a base in south Giruwa in mid-November 1942, the Giruwa Garrison consisted of three sections: Tsukamoto’s troops formed the South-west Sector Unit; in north Giruwa the remaining South Seas Force units led by Colonel Yokoyama Yosuke formed the Central Sector Unit; and closer to the coast, the line-of-communication unit formed the Rear Section Unit, which was later joined by the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of Yazawa’s 41st Regiment.

At the time Buna fell, the Giruwa garrison had already reached a crisis point. There were no medical supplies, while the number of the sick and wounded increased. Their hospital was a hospital in name only. Once soldiers were seriously wounded by shrapnel, they were left to suffer and die. The ammunition supply was only 15 rounds a day for each man’s rifle; many fought with captured Australian and American weapons. Earlier the Japanese came out from their defensive positions to launch counter-attacks and occasionally sent groups of heroic volunteers to silence the enemy guns, with some success. But as the enemy firepower intensified, making the jungle an open landscape, they were no longer able to leave their positions to attack. The only thing they could do was to hide themselves in their foxholes and fire at the approaching enemy.

The most serious problem was the shortage of food. A daily ration of rice was reduced from a meagre two gō (one gō is about 150 grams) to one gō in early December 1942. In January 1943 the ration was further reduced to two to four shaku (a shaku is one-tenth of a gō) – to the point that the soldiers could count the number of rice grains they received. They picked sprouting leaves of plants growing inside their base and cooked these with rice to make thin gruel. They ate anything edible, such as lizards, frogs, snakes, and mice. Food found in the bags of dead Australian soldiers was a special treat for the starving men, and some of them went even further, resorting to acts of cannibalism. The number of men who died of starvation was increasing. They were not only fighting the enemy, but also fighting for personal survival. In Giruwa some of the hunted became the hunters. They shot dead an approaching enemy soldier during the day and at night dragged the body to their position to eat. Cannibalism was taboo in Japanese culture, but the desire to survive was absolutely desperate.

In late December Allied troops started to intrude in the area between the central sector and the south-west sector, and on 9 January 1943 the south-west sector was completely isolated. On the morning of 12 January four enemy tanks appeared. The defenders fought desperately with the anti-tank gun they had so far hidden, and dispelled the enemy. But the anti-tank gun was destroyed by the intense Allied fire. Tsukamoto knew they would no longer be able to withstand the enemy’s next attack. Tsukamoto, prepared for possible court martial, decided to withdraw without authorisation. A serious problem for the withdrawal was how to deal with the sick and wounded who were unable to walk. In Japanese military culture, becoming prisoners of war was never an option; the soldiers were expected to fight until they died. Some of them were mercy-killed by their unit commanders; some were given a grenade to commit suicide, and some were left with guns and bullets, so they could fight to the last. In the evening Tsukamoto and his men left the base, heading toward the mouth of the Kumusi River under the cover of heavy rain. They heard the gunfire from their former base for the next couple of days, thanking their abandoned comrades who were still fighting to help them escape.

Tsukamoto’s unauthorised withdrawal was a surprise to the remaining troops in Giruwa. On the morning of 19 January the new commander of the South Seas Force, Major General Oda Kensaku, who had arrived at Giruwa only a month earlier, received an order for the force to withdraw to the mouth of the Kumusi River at 10 pm the next day. Next morning, when Oda sent the order of withdrawal to senior officers such as Major Koiwai Mitsuo and Lieutenant Colonel Fuchiyama Sadahide, the commander of the 47th Field Anti-Aircraft Gun Battalion, they were bewildered: they thought it impossible to break through the besieging enemy and felt it unbearable to leave behind those who could not walk. Fuchiyama decided to defend the base to the death. However, Koiwai soon realised the rumour of withdrawal had already spread among the men. Earlier all the defenders in the garrison had been united in readiness to die, but that was no longer the case. Fuchiyama and Koiwai had to find a way to withdraw and deal with the immobile men. Later that day Oda gave a specific instruction to leave behind those who could not walk, and took full responsibility himself. There were still over a thousand men fit enough to escape and a mass escape of this size seemed impossible. Miraculously their dead comrades made this seemingly impossible escape possible. There was one spot on the western side of the base where the enemy never came, near the former field hospital. Earlier in the battle the dead had been buried, but as their number increased, they were simply left there, making a pile of dead bodies. The strong stench had kept the enemy away from this place. At 10 pm the able men started to escape stealthily, unit by unit; luckily heavy rain too helped their escape.

After suffering starvation and diseases, and fighting against a superior enemy in a hopeless situation beyond imagining, the debilitated men in the Giruwa garrison had to retreat owing to the lack of supplies and support. But Koiwai noticed no one said, “The enemy was strong” or “We lost the battle”. Among about 11,000 Japanese defenders, including labourers, who had fought in the battle of Buna–Gona, only about 3,400 men survived.