Terms of surrender

With the Third Reich about to fall, the terms of Nazi surrender became as much about politics as combat.

On 30 April 1945, his empire crumbling around him, Adolf Hitler – Führer, leader of the Third Reich, and instigator of the Holocaust – committed suicide. He had spent his final days hidden underground in his Berlin bunker, barking fantastical orders for severely depleted and non-existent German armies to swoop in and save his capital. In his eyes, Germany was being let down by cowards and traitors who would not fight to the death, but instead were allowing Stalin’s Red Army hordes to advance with ease. It was more than a week after Hitler’s death that the war in Europe finally came to an end. What happened in those final days? How and why did Germany fight on, and how quickly did wartime allies turn to Cold War enemies once they knew that victory was assured?

By June 1944, in both east and west, the tide had turned against the Nazi war machine. In the months after the D-Day landings, the Allied Expeditionary Force, under supreme command of American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, pushed through occupied Western Europe and into Germany. But they faced a determined enemy who had offered stiff resistance when the Allies stormed the beaches of Normandy. The Allies had again taken severe casualties in the failed Operation Market Garden offensive in September, and in December suffered a shocking setback from the powerful German counter-attack in the Ardennes, at the battle of the Bulge. Eisenhower’s Great Crusade was not going to be a pushover.

In the east, Soviet leader Josef Stalin’s Red Army faced an equally monumental task. On 22 June 1944, exactly three years after Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Soviet forces launched Operation Bagration. They recaptured Belorussia, and pushed Hitler’s forces out of Soviet territory, through Eastern Europe, and eventually to Berlin (see Wartime Issue 66). Thousands would die in the final months of fighting in the eastern theatre as titanic armies clashed and millions of civilians were caught between them.

From absolute power to figure of derision: Adolf Hitler in 1940, and an Australian sergeant in the ruins of the Reich Chancellery, Berlin, 1946.

Terms of surrender

Outwardly, the Allied position on Germany’s immediate future was clear. In July 1944 Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin agreed that they would accept nothing short of an unconditional German surrender on all fronts: there had to be no doubt that Germany had been defeated and that victory was absolute. There were two reasons for this. First, in 1918 Germany had signed the Armistice while vast armies remained in the field and German boots remained on foreign soil. For many Germans at the time, it was inconceivable that they had lost the Great War, and the cause of their defeat must therefore lie elsewhere. This was the origin of the Dolchstoß (stab in the back) myth – that Germany had been betrayed by feeble politicians in Berlin. Hitler had been able to use the myth effectively when stoking his brand of radical nationalism, railing at the perceived injustices of Versailles as he rose to power at the head of a resurgent Germany dominated by the Nazis. In 1945, the so-called “Big Three” (Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States) would not allow that history to be repeated.

Berlin in ruins, 1945. The Brandenburg Gate and Reichstag can be seen in the foreground.

AWM P04054.006

Secondly, insisting on a universal surrender on all fronts was meant to reassure Stalin that there was no chance the Western Allies would conclude a separate peace, which would allow the Germans to concentrate their efforts in a continued fight against the Soviets in the east. Allied commanders were authorised to accept purely military surrenders from forces that directly opposed them; but at any higher level, the surrender would have to be signed by someone with authority to represent the entire German government and armed forces, and the capitulation would have to be made in the presence of authorised representatives of all the victorious Allies.

Thus, before Hitler’s suicide, the leadership of Nazi Germany and the Allies in many ways represented two immovable forces. Where the Allies would accept nothing short of an unconditional surrender on all fronts, Hitler would not allow surrender in any form. If the Third Reich faced being swept into the dustbin of history, Hitler was willing to let the German people go down with it. He openly expressed on a number of occasions his judgement that the German people did not deserve to survive him: in his view, it was better for all of them to die in a final stand than to surrender ignominiously to the enemy.

Hitler’s successors

After Hitler eventually did commit suicide, the unenviable job of becoming the Führer’s successor fell to Großadmiral Karl Dönitz, a fanatical Nazi loyalist. His devotion to Hitler was so intense that as late as 25 April 1945, the day that Soviet and American forces met at Torgau on the Elbe south of Berlin, he sent 10,000 lightly armed sailors to assist in the doomed defence of the landlocked capital. Dönitz’s promotion resembled the elevation of an unknown bureaucrat brought in to run a company after the death of a charismatic CEO: many Germans did not feel bound to him by oath, patriotic loyalty or any other measure. Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner, General of the Waffen-SS, upon hearing that Dönitz had been made president asked who Dönitz was, and proclaimed: “My forces and I are not bound by oath to him. I will negotiate on my own footing with the English at my rear.” Hitler’s other heirs-apparent had for the most part either abandoned their leader by fleeing Hitler’s bunker as the Allies closed in (as did Göring and Himmler in April), or committing suicide rather than face a post-Führer world (as did Goebbels and his wife, after killing their six children, in early May).

Dönitz inherited a Third Reich going through its death throes. When US and Red Army forces met on the Elbe, Germany’s remaining military forces had been split into two main pockets of decreasing resistance. Compounding their troubles, German armaments production had by this time ground to a halt, and German troops still in the field fought with ever-diminishing supplies, scrounged from stockpiles of parts and components. In the words of Australian journalist Chester Wilmot, by 1945 “German war industry, having consumed its fat, was eating its tail.” On top of the supply crisis, morale in the Wehrmacht was so poor that some German officers took to confiscating white handkerchiefs from their troops, lest they be used as white flags of capitulation. In the final weeks of the war, SS and police summarily executed up to 10,000 soldiers and civilians suspected of cowardice or surrender. If a white flag appeared in front of a building, every male in it was to be immediately shot.

The mostly Australian crew of “V” for Victory celebrate VE Day by their appropriately named aircraft, May 1945. AWM UK2855

Looking ahead

By April and May 1945, many in both the Axis and Allied camps had already turned their thoughts to post-war Europe. Many Germans, both civilian and military, focused on avoiding the advancing and vengeful Red Army – either by fleeing west, or seeking in vain a separate surrender that would allow them to focus on their eastern flank. Even when Hitler was still alive, German forces – such as the 80,000 troops of the 9th Army under command of General der Infanterie Theodor Busse – were disobeying orders to come to Berlin’s defence, and instead attempting to fight their way to the west. Dönitz believed that a large part of his role as new leader was to continue to fight, not in some vainglorious attempt to resurrect the war effort, but simply to buy time for more Germans to escape to the west. He later wrote in his memoirs that it pained him to send German soldiers to die fighting in the east when the war was clearly lost. But the alternative – immediate surrender, thus condemning millions of German soldiers and civilians to Soviet occupation – “was a burden too heavy for the conscience of any man.” Dönitz made no secret of his views on fighting in the east. Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock, former commander of Army Group Centre, in his diary summarised Dönitz’s radio address to the German people on his appointment as president: “The only purpose for continuing the fight is to save the largest possible part of the German population from the clutches of the Bolsheviks. Fight … against the Anglo-Saxons only if they seek to interfere with this plan.”

Stalin, convinced that the Westerners were at best seeking to push their area of control eastwards, and at worst were entertaining the idea of teaming up with the Germans to stem the red tide, pushed his forces east at a brutal pace. Marshal Georgii Zhukov, commander of the Soviet 1st Belorussian Front, wrote that during the attack on Berlin, for example, Soviet actions were not dictated so much by operational concerns as by the “military-political situation” unfolding in Europe. Zhukov accepted the formal surrender of Berlin on 2 May after weeks of brutal street fighting in which some 360,000 Soviet and Polish soldiers and untold numbers of civilians had lost their lives. Thousands more fled as refugees, or fell victim to the fury of vengeful Red Army troops. The rape and pillage of Germany and eastern Europe by the Red Army in the final months of the war has been openly discussed in many Western accounts, but the subject remains taboo in Russia to this day.

Surrender

Despite Stalin’s paranoia, the Western leaders generally strove hard to ensure the surrender was indeed universal. On hearing that Himmler, via Red Cross representatives, had made contact with the Western Allies with a view to negotiating a separate surrender on 22 April, Churchill immediately informed Stalin of the development before the Soviet leader’s suspicions could get the better of him. Again, when the people of Prague, aided by Soviet defector Andrei Vlasov, rose up against the Germans on 5 May, Churchill pleaded with Eisenhower to allow General George Patton’s Third Army to push east and assist the Czechs, thus potentially reducing Stalin’s post-war control in the area. But Eisenhower refused to push beyond the agreed lines: his focus was on the military defeat of the enemy, not post-war politics and spheres of influence. The Red Army entered Prague on 9 May after attacking and capturing the 600,000-strong remnants of German Army Group Centre in Czechoslovakia and eastern Germany.

On the same day that the Prague Uprising began in the east, US General William Simpson’s US Ninth Army began to accept the surrender of wounded troops from Busse’s forces south of Berlin on the Elbe. But Simpson could accept only wounded soldiers, and civilians were forced to stay put. In an example of the delicate diplomatic situation that dominated the chaotic times, he was bound by the agreement struck among the Allies: civilians should, so far as possible, remain in their home provinces.

North of Berlin, where British, Canadian and US forces had advanced from France towards the Baltic coast, enormous pockets of German forces remained holed up in the Netherlands, Denmark, and northern Germany. British Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery was less diplomatic with regard to the Soviets than his American counterpart. He revealed in his memoirs that by late April 1945 he “was concerned the oncoming Russians were more dangerous than the stricken Germans”. He wanted to push as quickly as possible to the Baltic coast, not only to break the Germans, but to form an east-facing flank to stop the Soviets from pushing into the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, and from there into Denmark. As part of this plan, on 2 May the British 11th Armoured Division entered Lübeck, north-east of Hamburg; in doing so they also captured the last German U-boat base and prevented enemy movement between Germany and Denmark.

Despite Montgomery’s concerns about Soviet intentions, when German representatives eventually offered him partial surrenders, he did follow the agreed procedures. On 3 May Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel sent a delegation to Montgomery’s headquarters at Lüneburg Heath, south of Hamburg, offering the surrender of three German armies fighting against the Red Army north-west of Berlin. Montgomery refused, and informed the Germans that those armies should surrender to the Soviets (though if soldiers came to his lines with their hands up, he would accept them as prisoners of war). Generaladmiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg retorted that to surrender to the Soviets was unthinkable, and that the red savages would put them all in labour camps. Montgomery’s reply was blunt: “I said the Germans should have thought of all these things before they began the war, and particularly before they attacked the Russians in June 1941.” When the German delegation returned the next day offering to surrender all German forces in north-west Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands, Montgomery accepted. The new offer appeared to be purely military, and was compatible with the agreements regarding partial surrender of directly opposing forces.

Marshal Zhukov signing Germany’s unconditional surrender on behalf of the Soviet Union, May 1945. AWM P02018.385

Signing off

On 5 May a German delegation arrived at Eisenhower’s headquarters at Reims in France to begin negotiations for a final capitulation on behalf of Dönitz’s government. They were bluntly informed, according to Eisenhower, that “there was no point in discussing anything … our purpose was merely to accept an unconditional and total surrender.” Friedeburg, who had offered the surrender of the German forces in the north to Montgomery only days before, told the Allied negotiators that he was not authorised to offer a universal surrender; he contacted Dönitz, who sent Generaloberst Alfred Jodl to the Allied camp to assist. Eisenhower, who knew that the Germans had nothing to bargain with and suspected that they were merely stalling to buy more time to escape the Soviets, laid down an ultimatum: if the Germans did not offer a universal surrender, he would close the Western Allied lines, and thus prevent any more refugees heading west. Dönitz promptly authorised the German representatives to sign the surrender, which they did in the early hours of 7 May: all hostilities were to cease at 23.01 hours Central European time on 8 May.

General Ivan Susloparov, the Soviet representative at Reims, was in a difficult situation: he did not have instructions from Moscow indicating what he was to do, and did not want to displease Stalin by acting beyond his brief. At the same time, if he did not sign on Stalin’s behalf (authorised or no) he might leave the Soviet Union off the surrender altogether and give credit for victory to the West – also attracting Stalin’s wrath. In the end, he did sign the document, but added a qualification that would allow Moscow to make further negotiations if necessary. The ink barely dry, he received a frantic message by telegram from Stalin’s war council: “Do not sign any documents!”

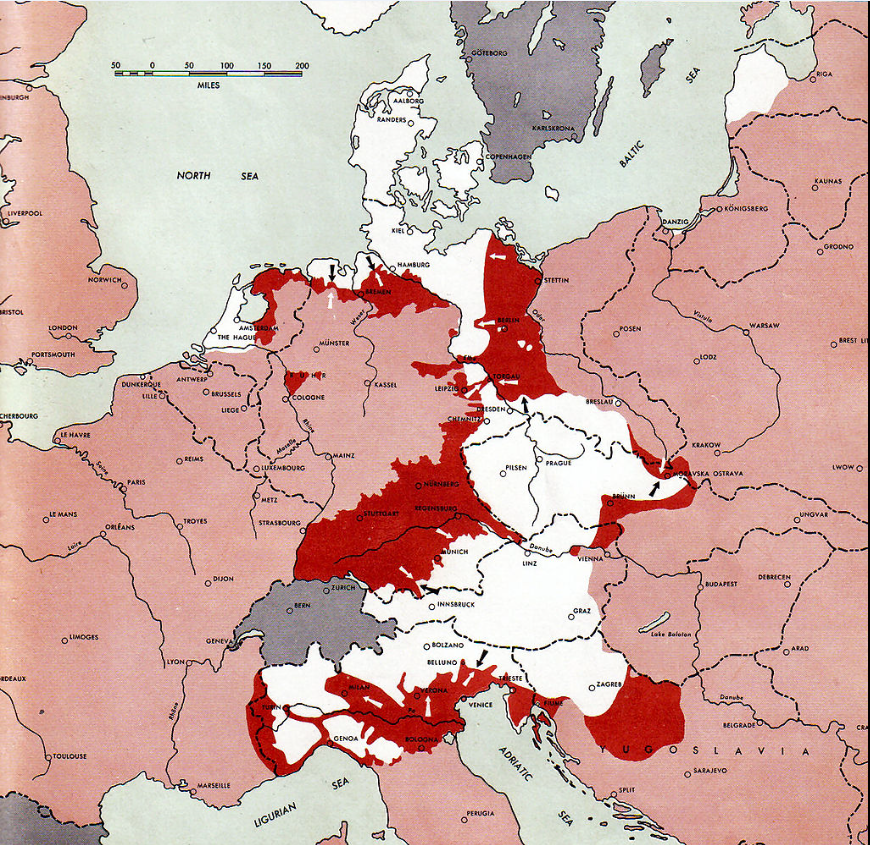

An August 1945 map showing Nazi Germany in its final days. Areas occupied by the Allies are shown in pink; areas of continued fighting are shown in red; the final areas controlled by the Nazis is shown in white (photo courtesy wikicommons).

Before the fall: the last days of Nazi Germany. Pink, in Allied hands; red, the last fighting; white, in Nazi German hands at the fall. (courtesy Wikicommons)

To ensure the Soviet Union was properly represented on the surrender documents, a furious Stalin organised a second and more elaborate surrender signing ceremony to be held at Zhukov’s headquarters on the outskirts of Berlin at 23.01 on 8 May, which was 9 May in Moscow. By the time this surrender took place, news of the defeat of Nazi Germany was widespread in the west, where 8 May is commemorated as Victory in Europe Day. As there were still pockets of fighting in the east, Stalin would not allow celebrations until his surrender was complete, and 9 May is celebrated as Den’ Pobedy (Victory Day) in Russia to this day.

It did not take long for the Cold War to emerge from the ruins of Europe, and the new struggle between the one-time Second World War Allies dominated world history until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The tension and mistrust that led to the Cold War were apparent during those final weeks of the Second World War, and historians the world over have long argued about who should be given the credit for the victory. In 1945, Eisenhower took a more conciliatory tone. In his Victory Order of the Day, issued in May, he congratulated his men for their victory, thanked them for their sacrifice, and stated:

Let us have no part in the profitless quarrels in which other men will inevitably engage as to what country, what service, won the European war. Every man, every woman, of every nation here represented has served according to his or her ability, and the efforts of each have contributed to the outcome. This we shall remember – and in doing so we shall be revering each honored grave, and be sending comfort to the loved ones of comrades who could not live to see this day.