Villains or victims?

On 27 February 1902, Harry “Breaker” Morant and Peter Handcock were shot by a British firing squad in Pretoria. Over a hundred years on, the controversy over the rights and wrongs of the case continues.

Harry Morant, a drover and balladist, and Peter Handcock, a blacksmith, were lieutenants in the Bushveldt Carbineers, a regiment raised in South Africa early in 1901 to garrison the northern Transvaal, round up small bands of armed Boers, and bring in Boer families willing to sign an oath of allegiance to the British empire. They were convicted after a series of courts martial of the murders of 12 Boer prisoners. All parties agree – even Morant and Handcock admitted it – that the men shot the prisoners. The main issue concerns the justice of the convictions and the sentences.

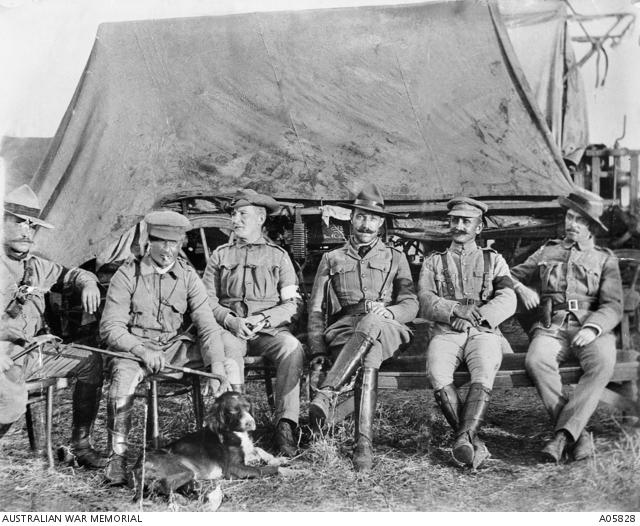

A group portrait of the officers of the Bushveldt Carbineers. From left to right they are: Lieutenant Peter Handcock, Lieutenant Harry Morant, unknown, Captain Frederick Hunt and Captain Alfred Taylor. C956957

To help us understand the debate, Wartime invited comment from three historians: Dr Craig Wilcox, who is completing a history of the Boer War 1899–1902 for the Australian War Memorial, due out this November; Mr Nick Bleszynski, author of Shoot straight, you bastards! (2002), a just-published book on the affair; and Mr Bill Woolmore, author of another recent book on the subject, The Bushveldt Carbineers (2002) We posed three questions:

Were Morant and Handcock wrongly convicted and executed by the British authorities?

Wilcox

Morant and Handcock were not Australian soldiers but imperial volunteers in an irregular regiment raised in South Africa to serve with the British army. The British army and government, not Australia, held legal jurisdiction over the two men, and murder was then a capital crime.

Morant, Handcock and some other Bushveldt Carbineers officers were turned in by 15 of their own troopers after a spree of killings in which more than a dozen unarmed men died, generally Boers who wanted to end nominal status as combatants and sign an oath of allegiance to the British empire. No one denied killing the Boers, and no evidence was produced at the trial – or since, despite claims by Nick Bleszynski – that any order existed sanctioning these killings. This is not surprising, as it would hardly have sped victory to begin shooting former opponents who wanted to sign up to the cause.

Bleszynski

Yes. They admitted shooting 12 Boer prisoners, but claimed they had received orders to take no prisoners.

Despite attempts to cloud the issue by throwing up the spectres of Ned Kelly and Nuremberg, neither of which has any historical relevance to the Morant case, military law in 1902 was quite clear. If it had been proved that Kitchener issued the controversial orders, he and not Morant and Handcock would have been tried. Proof finally surfaced in the diary of Provost Marshal Poore, who admitted that the orders existed. He remarked that if they wanted to shoot Boers they should not have taken them prisoner first. As chief of the army police he knew full well what the “rules” were.

In any case, neither Nuremberg nor present legislation would have saved Kitchener. Had the case been tried in another era, Kitchener might have been sitting next to Göring or Slobodan Milosevic.

Woolmore

The men were badly dealt with in South Africa. They admitted to shooting certain Boer prisoners but only on orders, and at least some cases had been reported to Colonel F. H. Hall, commander of their area.

They endured solitary confinement for months and even the military chaplain was denied access to them. They were informed of the charges and the trial date at the last minute and had scant opportunity to prepare a proper defence or to contact defence witnesses. Army Headquarters scoured South Africa seeking witnesses to testify against the BVC officers while defence witnesses were dispersed. Prime defence witness, Colonel Hall, was rushed to India before the trials.

Communication with their families and friends in Australia, and even their government, was severed until the executions were a fait accompli. Their courageous armed defence of Pietersburg during the actual trials, and the condonation that warranted, was ignored.

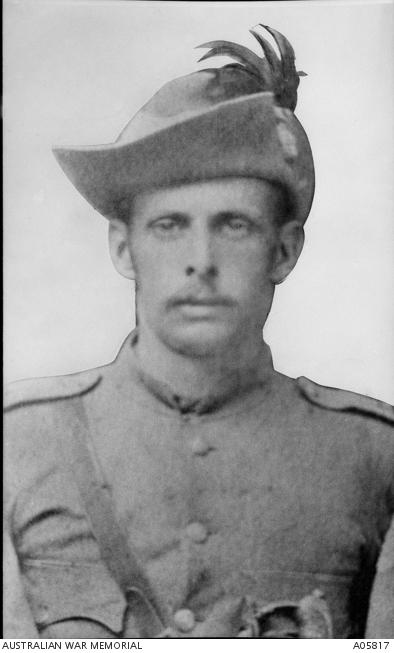

The 2nd South Australian Mounted Rifles in Adelaide before their departure for South Africa. Harry Morant, then a corporal, is sitting on the right at the front of the photograph. C41841

Is there any reason to see Morant and Handcock as victims of British military injustice?

Wilcox

The courts martial that convicted Morant and Handcock lasted six weeks, in an age when murder trials commonly lasted three days. The defendants had a lawyer of their own choosing. His defence was inconsistent, shifting ground from asserting that Morant was following orders to pleading that he was avenging the death of a fellow officer.

There is no evidence that Germany took any interest in the matter or that Kitchener intervened in the trials, but Kitchener wanted to make an example of Morant and Handcock. They were executed while Alfred Taylor, the officer who advised them, wriggled free of any punishment. Nor were other soldiers who killed unarmed Boers executed.

Taylor’s escape was shameful, but partial justice is better than none and often the only justice achievable. In any case, military law then relied on making an example of the few to rein in the many.

Bleszynski

Yes. The courts martial failed to punish anyone for seven murders that occurred before Morant arrived at Fort Edward and ignored the irregular units that carried out the same policy as the Bushveldt Carbineers.

“Two wrongs don’t make a right,” claimed the Judge Advocate, but neither is it justice. Also, when Pietersburg was attacked during the trial, the issue of condonation was not applied in Morant and Handcock’s case after they helped defend their prosecutors. According to a principle established by Wellington, any soldier called into service while on trial has their original offence set aside.

Baden-Powell applied the principle to a soldier who had murdered a journalist during the siege of Ladysmith. However, in the case of Morant and Handcock it was not even mentioned in mitigation. This, according to condonation expert Charles Francis QC, was “wrong in law”. Geoffrey Robertson QC regards the whole case as “unsafe”.

Woolmore

We have inherited from Britain the best civil justice system in the world but military justice (in most countries) tends to be defective in practice. It can be subject to expediency on active service and more liable to abuse.

This trial and execution was a serious miscarriage of justice and the point was not lost on the Australian Government as Morant and Handcock were probably the last Australian soldiers to face a British Army firing squad. The pleas of Sir Douglas Haig, on the Western Front in the First World War, for power to execute Australians failed to move the Australian Government.

Initially, the Australian people were swayed by official propaganda from South Africa, and some historians still pay undue homage. However, the trial process has been universally condemned by jurists from 1902 to the present day.

Whatever we might think about the outcome, the process was gravely flawed.

2nd Lieutenant Thomas of the Tenterfield Company, Mounted Infantry Regiment. A practising lawyer before his departure for South Africa, Thomas defended Morant, Handcock and Witton. C956048

Does the Morant–Handcock controversy deserve continuing attention by Australians today?

Wilcox

All parts of our history deserve attention, and controversy is a good thing for rousing interest. But the legend that Morant and Handcock were Australians wronged by the British army is merely legend. Despite some unease when they learned the news, most Australians at the time felt that Morant and Handcock had been justly dealt with.

Morant’s cause was taken up initially by a few writers looking for a white strong man who didn’t mind playing dirty to preserve the supremacy of his race. Much later, some urban progressives took up the cause. Secretly in love with strong men too, and offended by Australia’s British past, they were certain Morant must have been innocent simply because the dastardly Brits shot him. Lacking evidence, their only recourse has been to conspiracy theories where a few ambiguous jottings and even silences in the record are hailed as telling evidence of injustice on high.

Bleszynski

Yes. Despite the new evidence I have published in Shoot straight, you bastards! and eminent legal opinion that the case is “unsafe”, bodies such as the RSL and the government are unwilling to review the original verdict.

Craig Wilcox claims that it makes no difference – whatever evidence surfaces. Is he seriously claiming that the fact that Kitchener gave illegal orders to kill prisoners, denied any knowledge of it at the courts martial and then coldly sentenced them to death makes no difference to the way we perceive the crimes of Morant and Handcock and the reputation of Kitchener?

As Australia continues to evolve and move towards a republic, it is important for us to make up our own minds about such historical issues – even if they go against the official historical line or offend old imperial allies who have yet to deal with their own Morants and Handcocks.

Woolmore

Ongoing debate is important as there are lessons in history to be learned. It is not about making heroes of the men. It is about seeing that they receive the justice and consideration they were denied in 1902.

The officers on the courts-martial appeared to be honest and fair even if their findings were debatable. Kitchener, however, after ignoring the court’s recommendations for mercy and confirming the death sentences, found it necessary to lie and mislead the Australian Government and people about the affair.

The most senior Boer general, Louis Botha, when asked in 1904 if the Boers wanted George Witton (another accused) kept in prison, replied, “No, we do not – and we’re sorry that the other men were shot”.

If the military leader of the enemy during the war saw cause for clemency, should we, a hundred years later, judge our own Australian soldiers more harshly?