The Royal Australian Navy fleet entry of 1913

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is hosting an International Fleet Review, to be held in Sydney from 3 to 11 October 2013. This high-profile event, which will showcase ships from some 20 nations, is being held to mark the centenary of the first fleet entry of the fledgling RAN into Sydney in 1913.

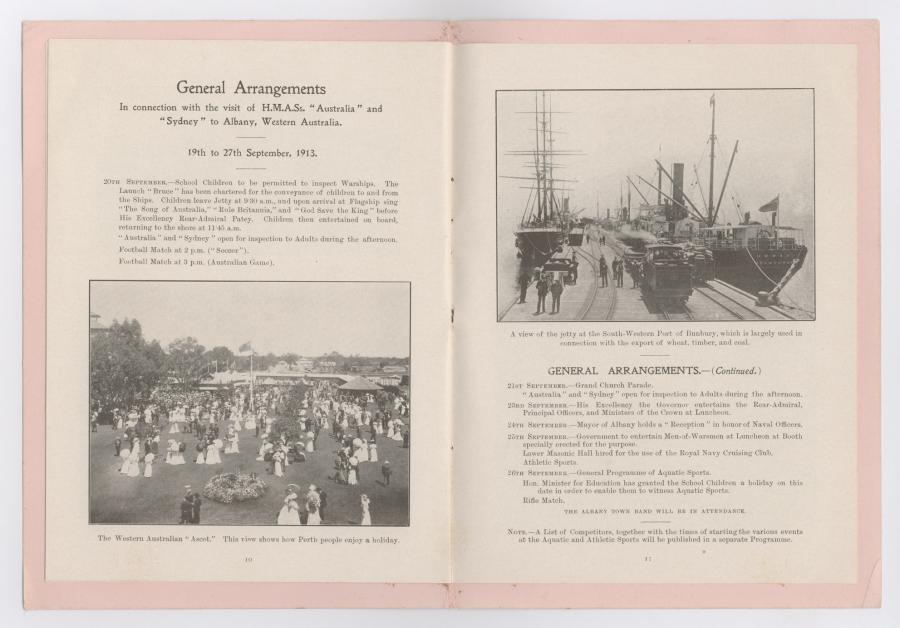

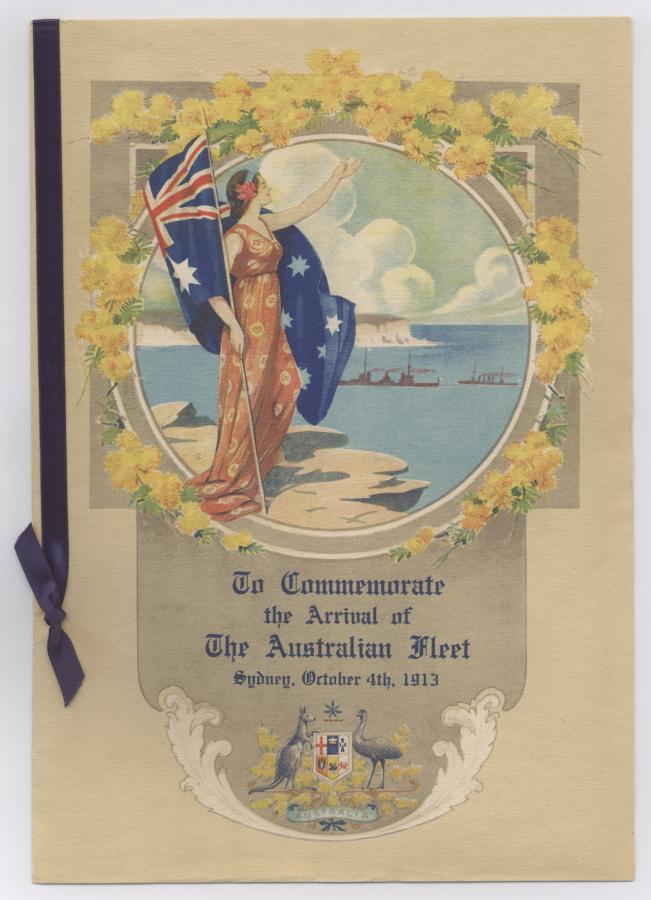

The arrival of the Australian Fleet into Sydney Harbour, for October 1913.

Why was the arrival of the RAN’s first fleet important?

The fleet entry of 1913 meant Australia now had a credible ocean-going fleet. The fleet’s arrival signified the final realisation of the recently established RAN. The Minister for Defence, Senator Edward Millen, declared, “Since Captain Cook’s arrival, no more memorable event has happened than the advent of the Australian fleet. As the former marked the birth of Australia, so the latter announces its coming of age.” The fleet entry was indeed a significant achievement, as prior to 1913 Australia had largely relied on Britain’s Royal Navy for its naval defence.

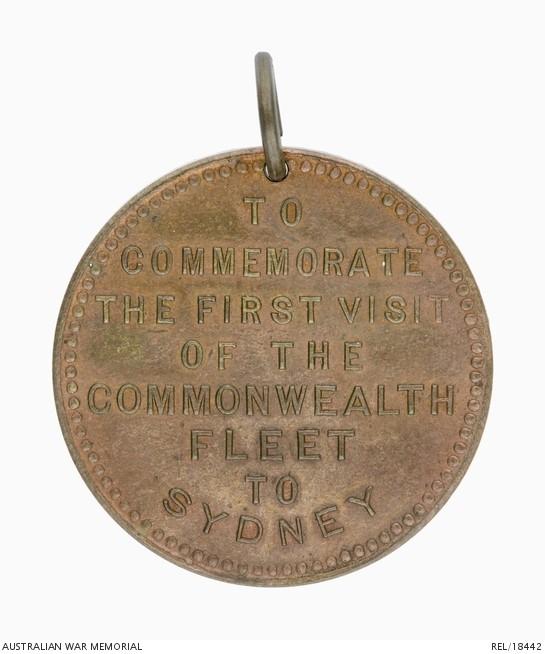

Commemorative medalet : First visit of the Commonwealth Fleet to Sydney, 4 October 1913, front.

Commemorative medalet : First visit of the Commonwealth Fleet to Sydney, 4 October 1913, back

The protection of Australian waters has formed an essential part of the nation’s approach to strategic defence since colonial times. A strong navy was needed not just to deter potential threats by foreign powers, but also to protect the extensive shipping routes and trade centres upon which Australia’s economy depended from pirates and raiders.

This naval defence was paid for by Great Britain. However, since the Napoleonic wars of the early nineteenth century, Britain had been downsizing the Royal Navy – a policy felt particularly in outlying colonies like Australia. With the dangers posed by increasing Russian naval power, demonstrated during the Crimean War, many colonists felt that the naval protection of Australia should be given more priority.

In response to appeals made by Australian colonial ministers in 1859, Britain gave Australia its own permanent Naval Station and Squadron, thereby recognising Australia’s distinct territorial significance and its strategic concerns.

Black full dress tail coat : Lieutenant F O Handfield, Victorian Colonial Navy

In an attempt to shoulder some responsibility for their own defence, several colonies had already begun to invest in local infrastructure, raise forces, and obtain their own ships. Ships such as HMCS Victoria, a steam-powered sloop obtained by the Victorian government in 1856, served the colony by providing a measure of coastal defence, and by conducting maritime rescue operations, survey operations, and mail runs. Victoria also served the interests of the British government through logistical support, coastal patrols, civilian evacuation, and even shore bombardment during the New Zealand Wars of the mid-nineteenth century.

Telescope used for navigational purposes by officer aboard HMCS Victoria

However, the British Government wished to discourage the development of colonial navies. It was clear to the British Admiralty that a more effective naval scheme would be for the colonies to contribute money to be put towards maintaining the Royal Navy.

While many colonists argued over how much should be contributed, several of the colonies, particularly Victoria, enthusiastically pursued the building of their own naval defence forces. In 1865, the British government passed the Colonial Naval Defence Act, which at last granted the colonies formal approval to assemble, sustain, and operate ships and personnel for self-defence, and to establish a force of volunteers to form part of the Royal Naval Reserve.

A wood engraving published in 'Engineering' in 1868 of one of the designs for the 'Cerberus'.

Sailors of the NSW Naval Brigade during a training exercise, probably on the coast of NSW, c. 1895

However, paying for it all proved more difficult. In 1859 the British government had stationed a small force of Royal Navy warships in Sydney Harbour known as the Australian Squadron. And so, in 1887, in the face of the inability of the colonies to adequately fund and man their own navies, this Australian Squadron was augmented by the Auxiliary Squadron to address the need for a well-maintained and well-trained sea-going navy. These additional Royal Navy vessels were managed by the Commander in Chief of the Australia Station, and could not be redeployed elsewhere without the consent of the colonial government. Although costs were shared between Britain and Australia, this was nevertheless a further step towards the creation of a recognisably Australian navy.

Torpedo Gun Boat HMS Boomerang (EX HMS Whiting) showing her starboard side. Boomerang was one of seven warships supplied and manned by the Royal Navy as an Auxiliary Squadron for the defence of Australia.

Third Class Protected Cruiser HMS Katoomba of the Australian Auxiliary Squadron of the Royal Navy, at anchor in Hobart, Tasmania, 1903.

Arrival of the Australian Auxiliary Squadron of the Royal Navy at the Man O’War Steps, Sydney, NSW, 1891.

By the late nineteenth century, many Australian politicians and naval commanders, such as Vice Admiral William Creswell, believed that a homogenous national navy was essential to meet the unique needs of the colonies. As an extensive island continent, wholly reliant upon the sea for communication and trade, Australia was especially vulnerable without a formidable navy. With Federation in 1901, the colonial navies of each Australian state united to become the Commonwealth Naval Forces, and the fledgling Australian navy was born. The Australian government became responsible for protecting its citizens and territory, even if imperial support was still required for blue-water defence.

Portrait of Rear Admiral Sir William Rooke Creswell KCMG KBE CMG (1852-1933).

Unfortunately, the quality of the naval vessels in the Australian colonies had deteriorated in the late nineteenth century, particularly in the face of the developing naval arms race between Britain and Germany which drove rapid technological advances in ships and equipment. The Commonwealth Naval Forces inherited a fleet that was quickly becoming obsolete – made worse by the removal of the Auxiliary Squadron in 1902–03 and the replacement of the ships of the Australian Squadron with inferior vessels in 1905.

In Australia, debate raged over these unpopular measures, but it unfolded against a background of the sense of loyal cooperation and reliance that many felt for the mother country. Affordability, practicality, strategic defence policies, national interests and ownership all came into play. As Australian representatives, including Creswell, recommended changes to Australia’s naval capability, the pressure on the Admiralty to reduce expenditure led Britain to concede that Australia should obtain ships which would ease their reliance on the Royal Navy.

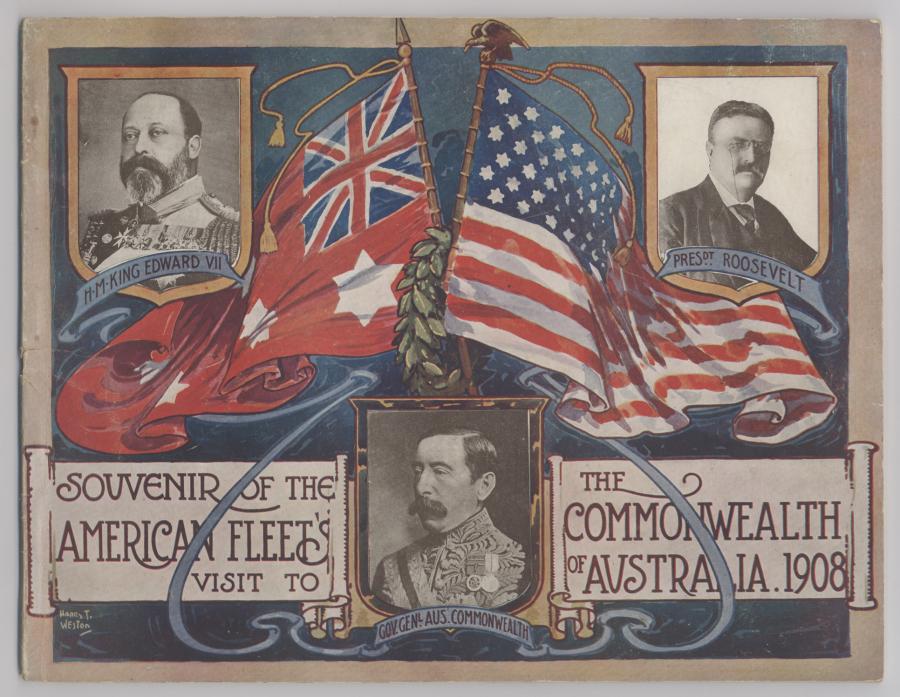

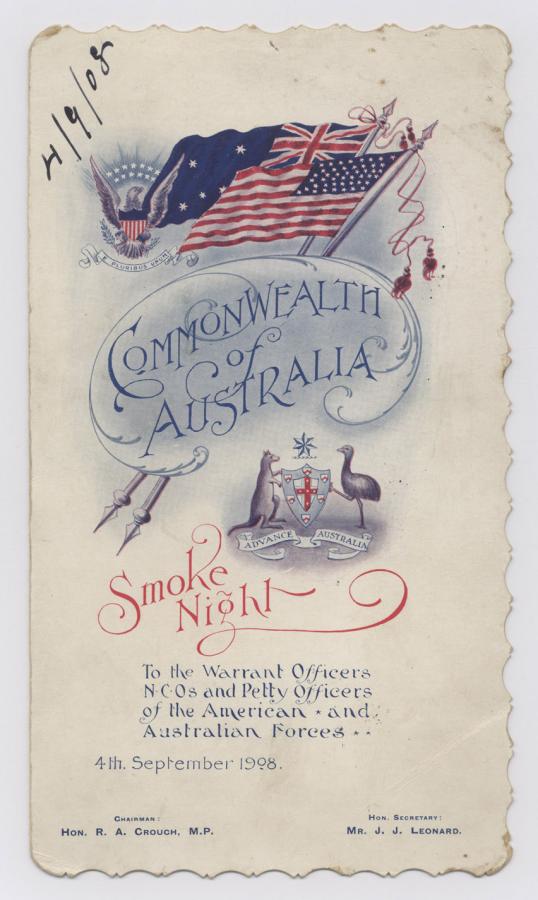

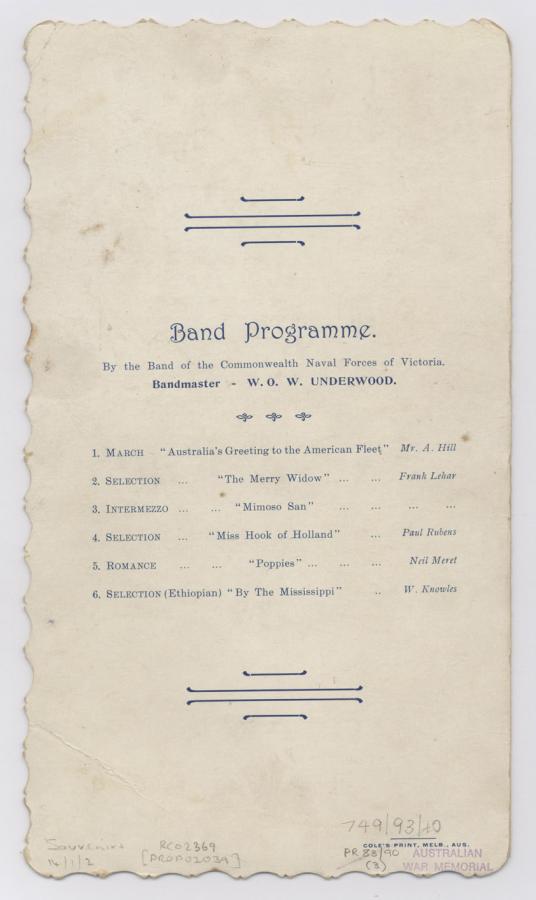

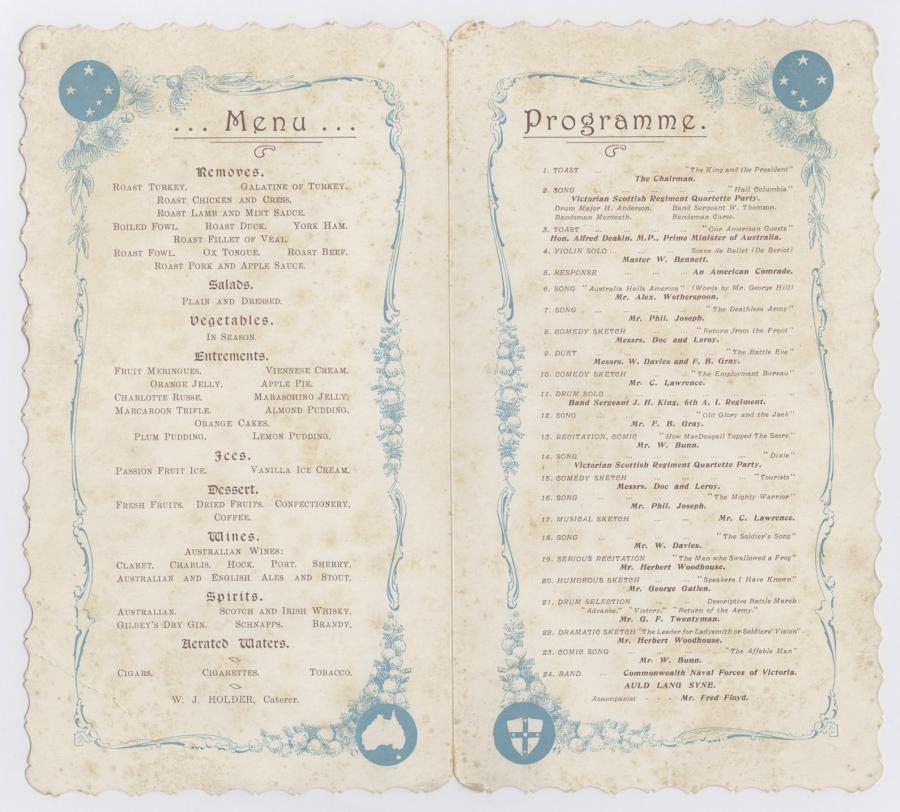

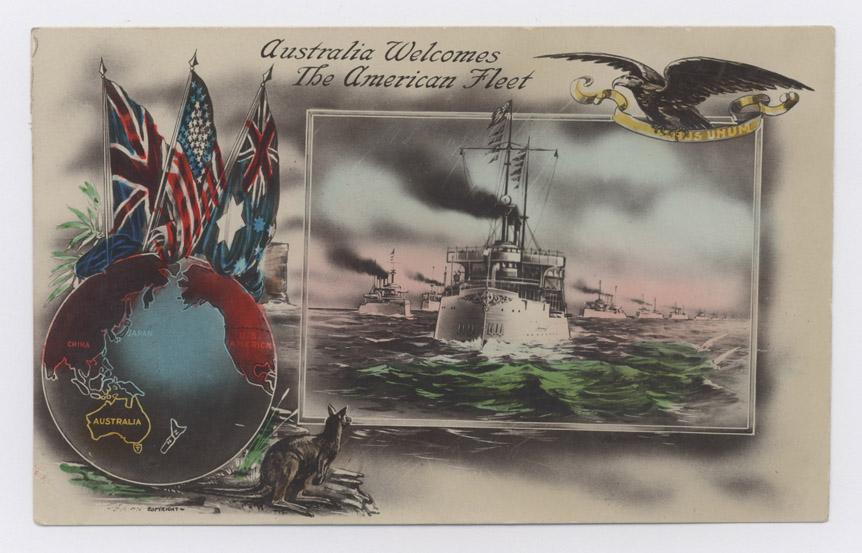

In 1908 America’s Great White Fleet visited Australia as part of a world tour. It was a stunning illustration by the United States of their defensive capability, and the spectacle both excited and inspired many Australians. The timing of the fleet’s visit helped to highlight the need for a completely self-funded, self-directed Australian navy, complete with modern sea-going ships.

The British increasingly concentrated their resources on the German threat, so it was hardly surprising that the need for a self-contained Australian Fleet Unit was raised again at the Imperial Conference of 1909. In the midst of increasing Japanese, American and Chinese influence in the region, the Admiralty acknowledged that the best option was for Australia to manage its own Fleet Unit. And so it was agreed that the Australia Station, and the Imperial dockyards and shore establishments, would be transferred to the Commonwealth.

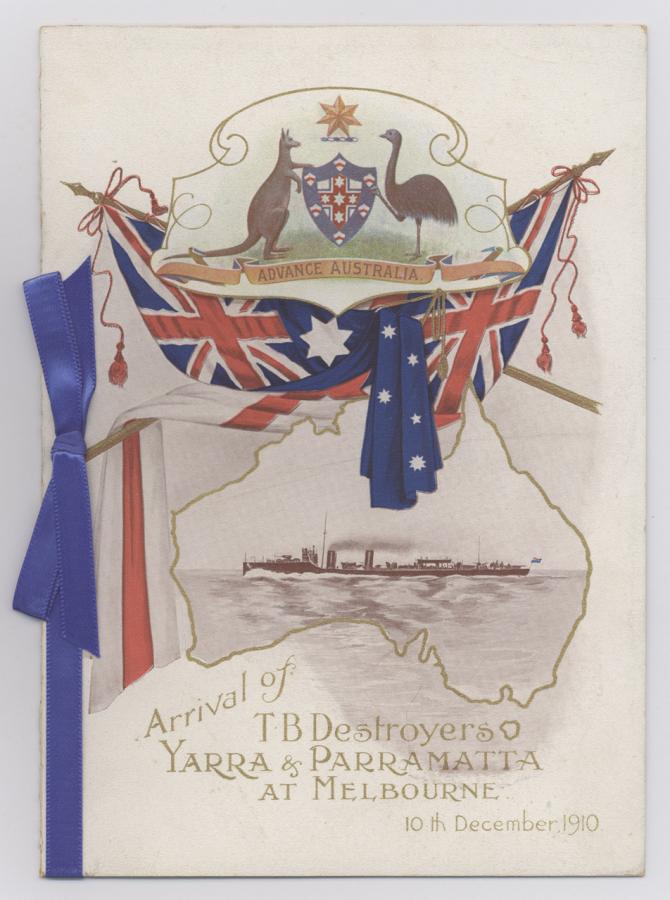

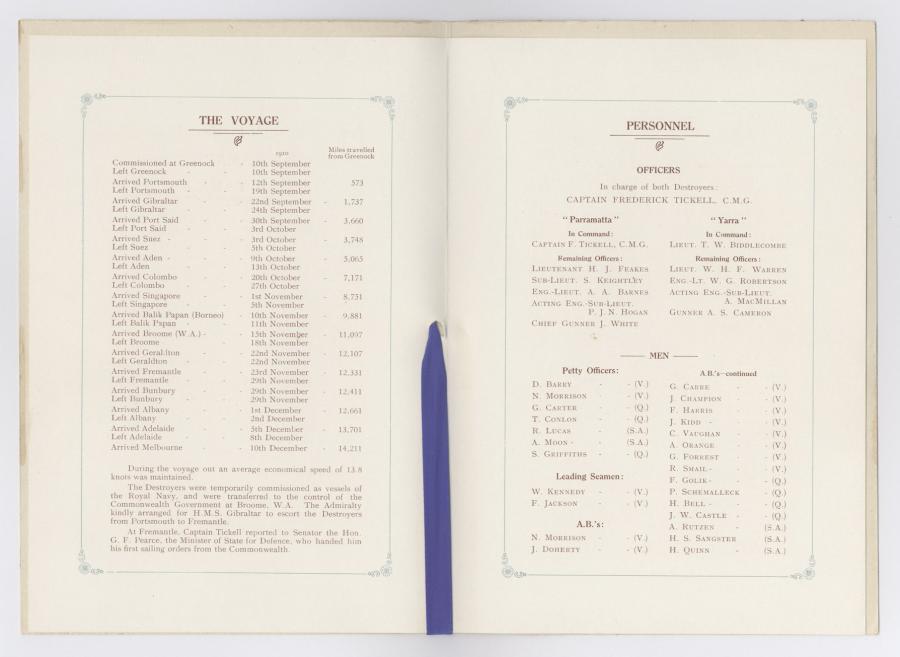

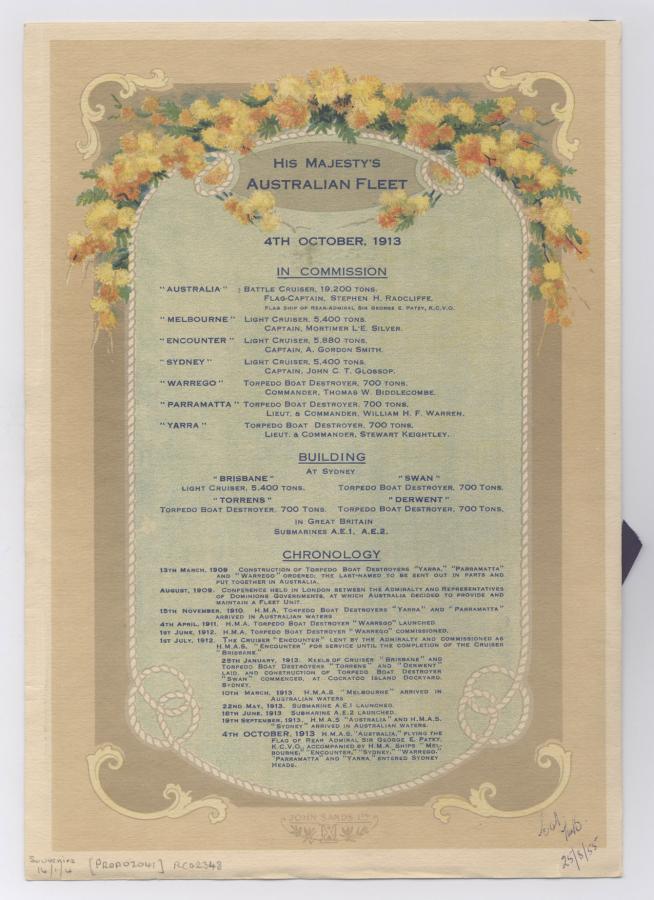

The final stages of the RAN’s development were in motion. The Australian Naval Defence Act of 1910 provided the legislative authority for the navy, allowing for the establishment of training establishments, a Board of Administration, and provisions for service conditions. The construction of ships was quickly arranged. The first ships, HMAS Parramatta and HMAS Yarra, arrived in Australia in 1910.

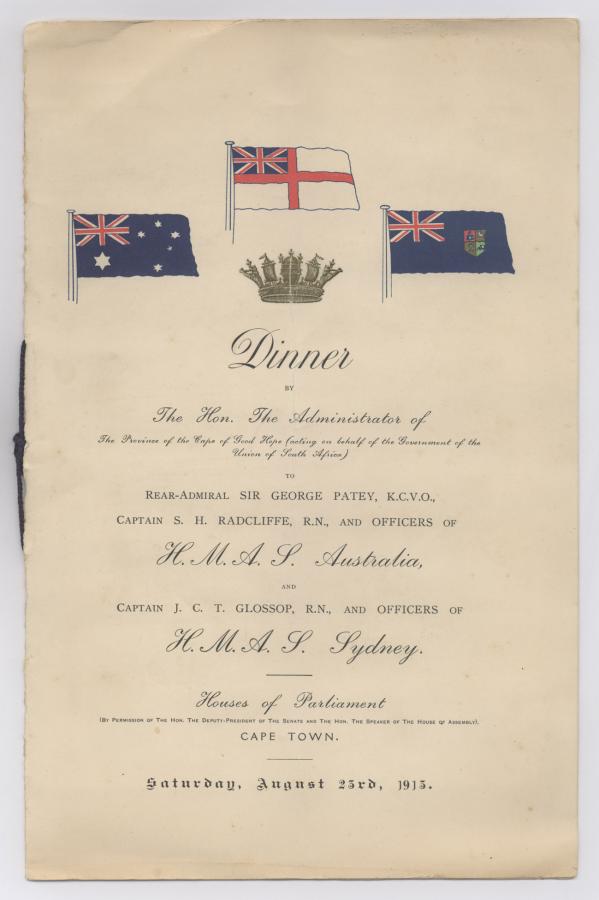

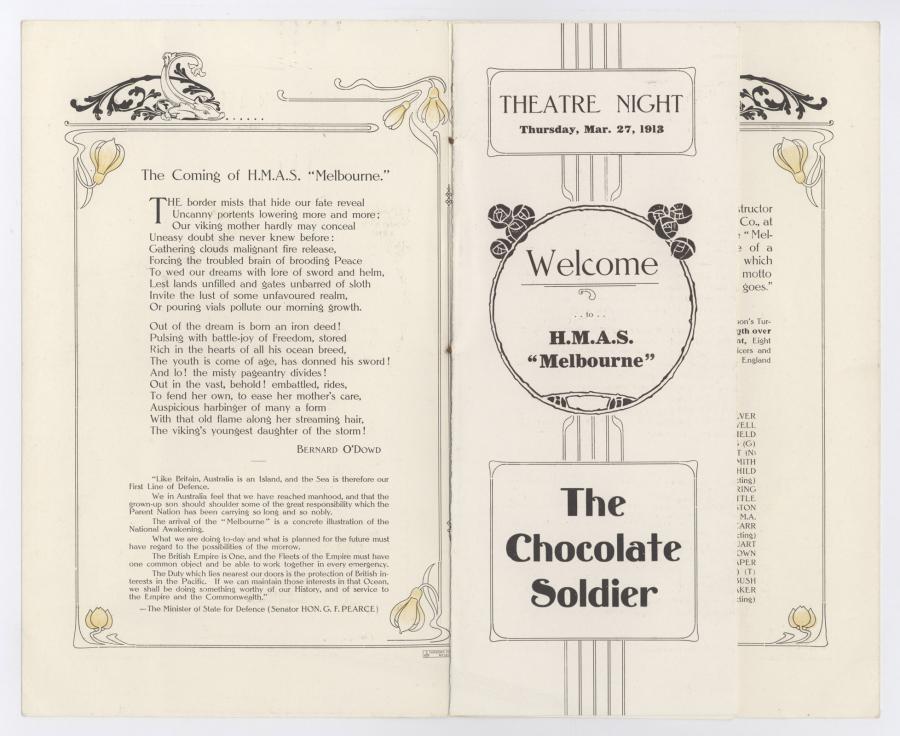

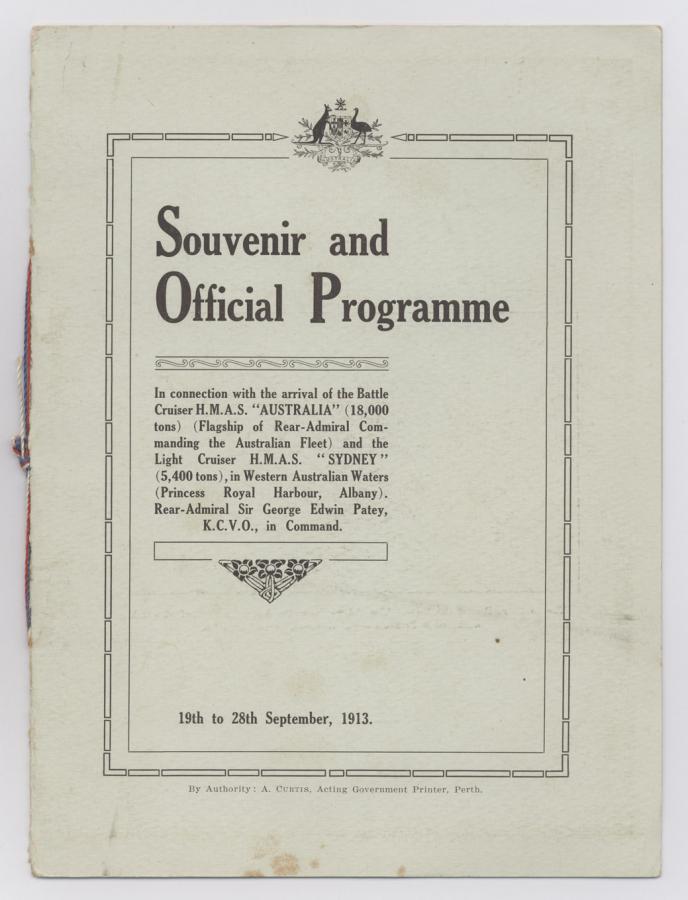

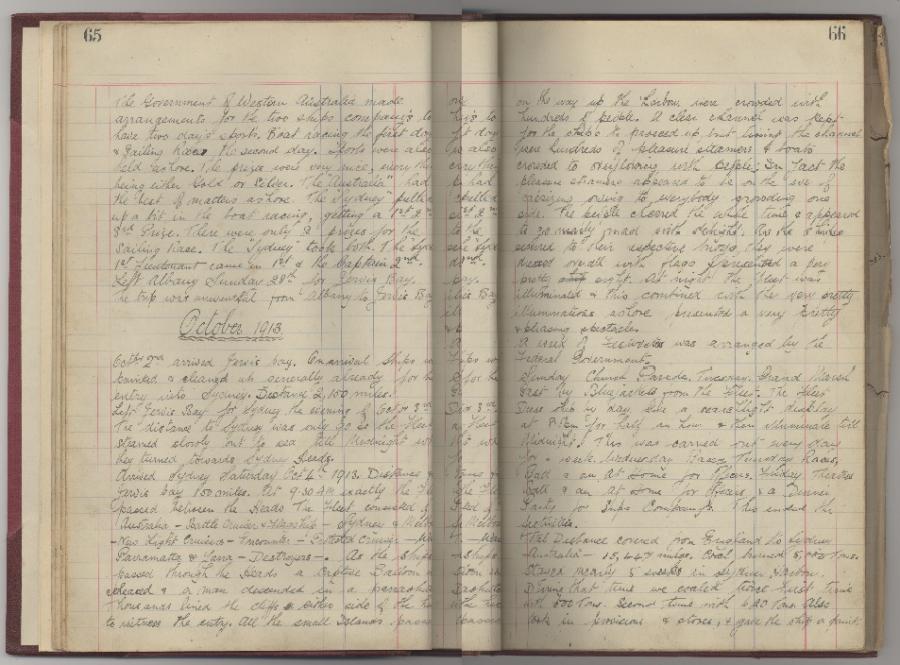

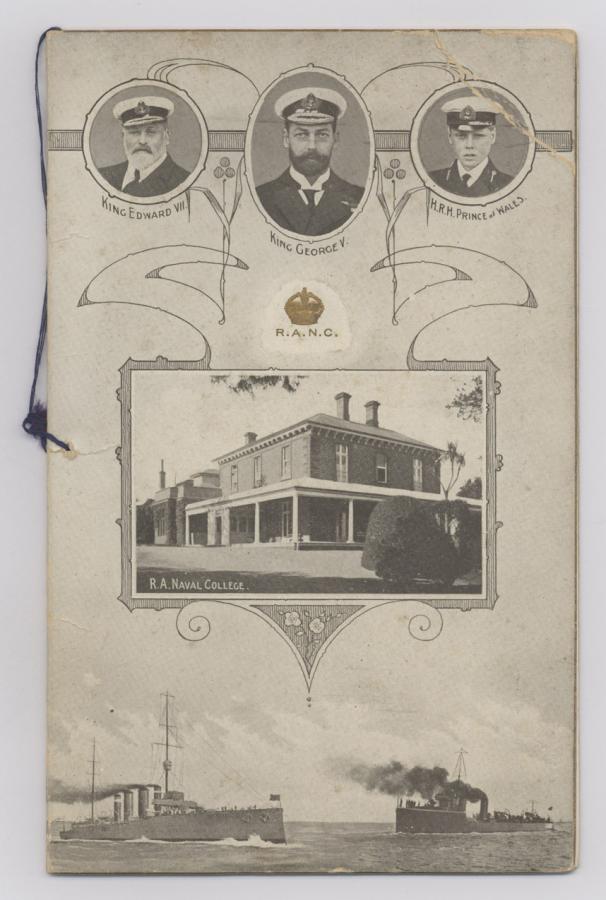

On 10 July 1911, King George V bestowed the title of “Royal Australian Navy” on Australia’s Permanent Naval Forces and the title “Royal Australian Naval Reserve” on the Citizen Naval Forces. Ships were formally granted the prefix “His Majesty’s Australian Ship” (HMAS), and the Australian flag replaced the Union Jack at the jackstaff. The creation of shore establishments and administrations, and the recruitment of personnel, followed hastily in anticipation of the completion of the new fleet. Several ships, only recently built, had to make the long voyage from British shipyards to Australia. Their journey was marked with ceremony from Britain to South Africa.

On 4 October 1913, the RAN finally displayed the new fleet to the Australian public in Sydney. Thousands of people came out to view the fleet. As one of the first national institutions of significance since Federation, the fleet was a striking symbol that Australia was now a self-determining, self-reliant nation. The flagship was named HMAS Australia, to avoid preferential treatment of a particular state. It led HMA Ships Melbourne, Sydney, Encounter, Warrego, Parramatta and Yarra into Sydney Harbour. The formation of the RAN and its fleet –funded and managed by Australians, for Australians – was widely recognised as signalling Australia’s maturity as a self-governing nation.

From left to right, the battle cruiser HMAS Australia (I) and the Light Cruisers HMAS Melbourne (I) and Sydney (I) dressed overall after the first entry of the Australian Fleet Unit into Sydney Harbour, 1913-10-04.

A sweetheart brooch, likely to have been produced to celebrate the commissioning of HMAS Melbourne (I), a Chatham class light cruiser, into the Royal Australian Navy in 1913.

Brass bell from battle cruiser HMAS Australia. Black lettering on both sides of the bell reads 'H.M.A.S. AUSTRALIA 1913'. The headstock is painted grey and part of the attachment point has broken off and is missing.

The RAN had grown from some 400 personnel in 1911 to some 3,400 in 1913, with 16 vessels. Today its more than 16,000 personnel and 53 vessels continue to serve Australia.

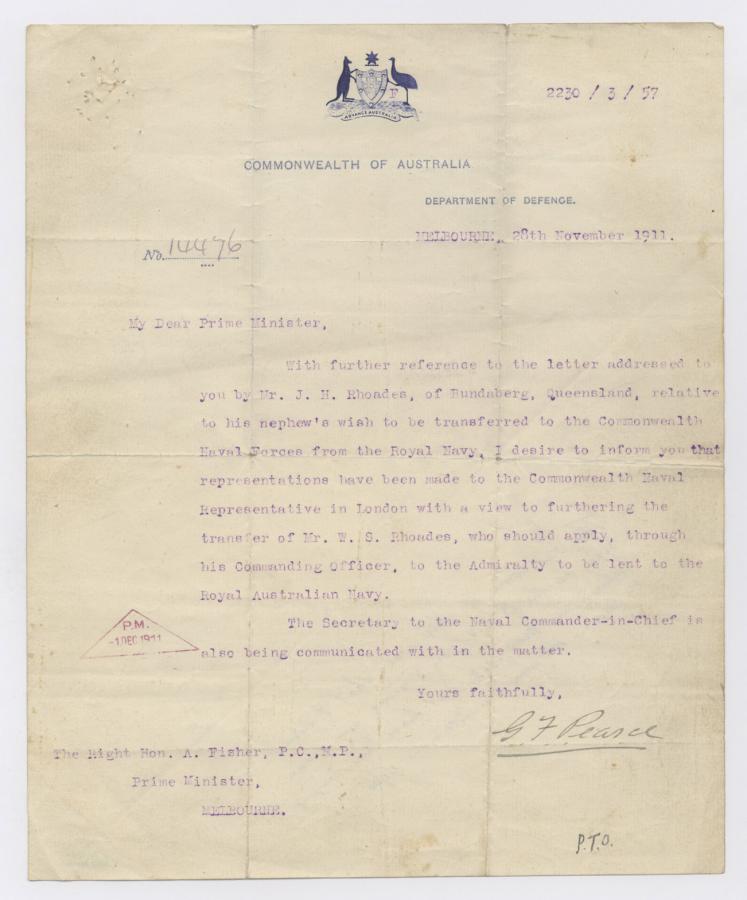

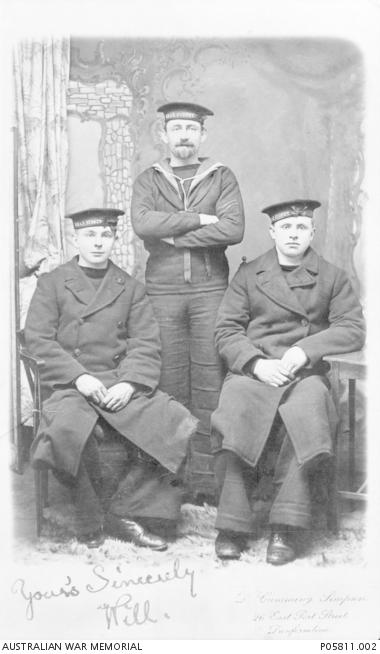

In 1913 many naval personnel, albeit Australian-born, were on loan from the Royal Navy, having previously served with the Royal Navy in Australia. Others were British-born but volunteered to join the RAN and made a new life for themselves in Australia.

To have men with Royal Navy experience in the new fleet was useful during the initial period of development. Building on the existing structure of the Royal Navy allowed Australia to avoid having to establish a completely new navy.

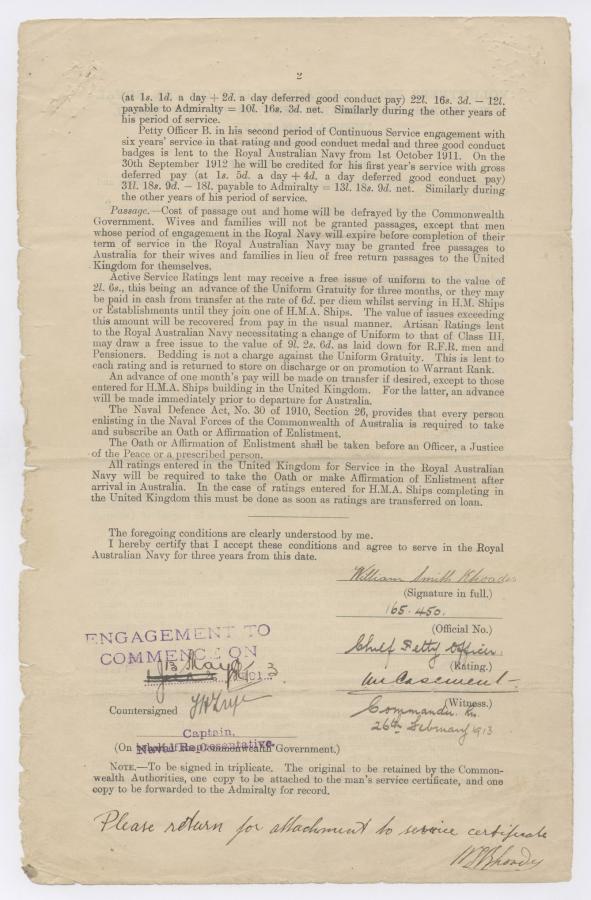

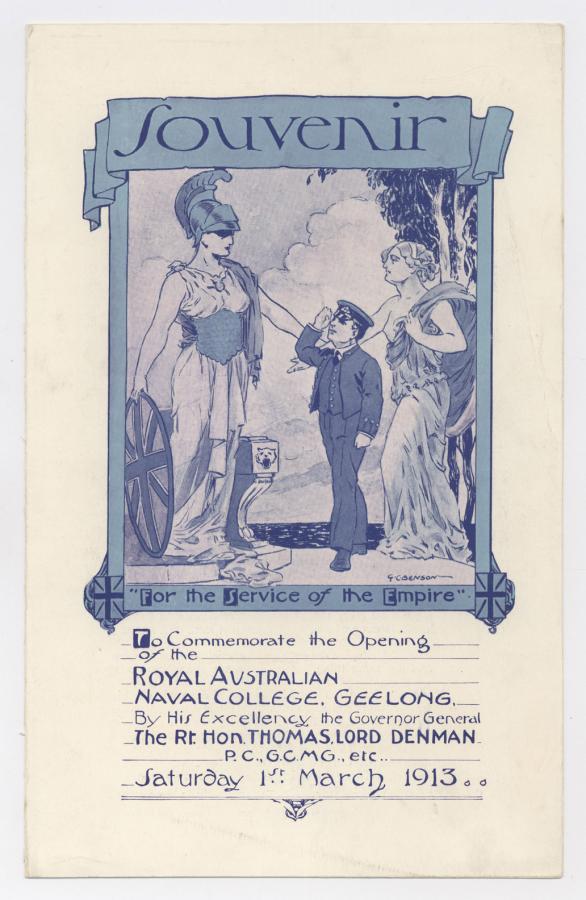

Naval schools and colleges were set up to train Australian service personnel. In 1911 HMAS Creswell had been established as the Royal Australian Naval College (RANC).

During the construction phase, the college was temporarily located at Osborne House, Geelong. The RANC opened in 1913, and relocated to Creswell in 1915.

Since 1913

It did not take long for the new fleet to prove its worth. During the First World War, the RAN served as a deterrent, preventing the Germans from attacking Australian ports, taking supplies, and cutting off communications. On 9 November 1914, HMAS Sydney became the first Australian vessel to engage and defeat an enemy vessel, the feared German surface raider SMS Emden, at the Cocos-Keeling Islands. This first victory for the new navy, and Sydney’s success thrilled the nation.

Since that time, the RAN fleet has served the Australian people in numerous military campaigns and by performing numerous peacekeeping and aid missions around the globe. Locally, the RAN endeavours to protect our fisheries, habitats, and other resources, and to provide general border security.

The International Fleet Review of 2013 will symbolise a century of Australia’s naval fleet in operation. In the words of The Singleton Argus, 4 October 1913, “That our fleet may never be called upon to engage in battle is the wish and prayer of all, but we recognise that even should they never fire a shot, they will have done their duty.”

International Fleet Review of 2013

Details on the International Fleet Review of 2013 can be found on the Royal Australian Navy’s International Fleet Review site:

Search the Memorial’s Collections

The Australian War Memorial holds naval material from the period which may be useful to researchers.

AWM266

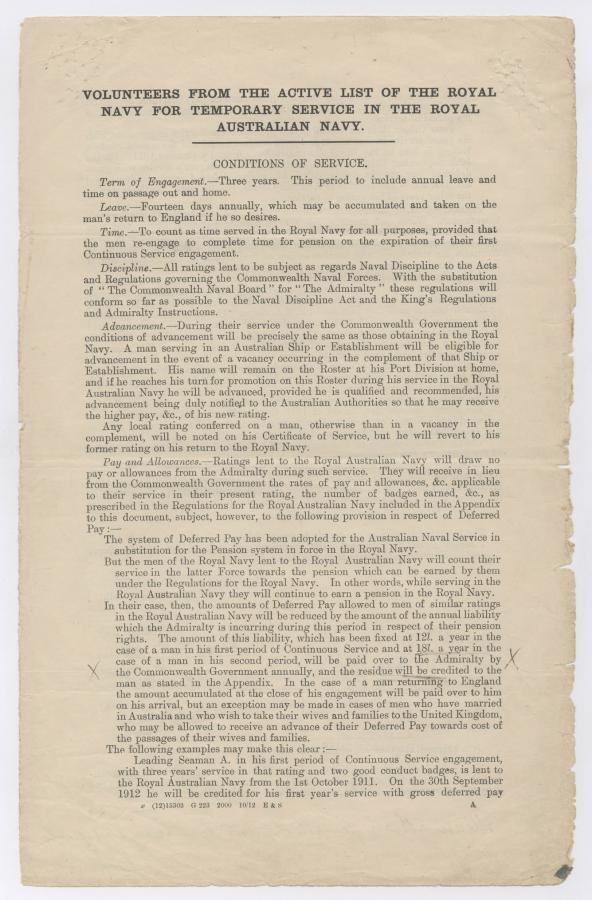

The Official Records series AWM266: Australian Naval Force (ANF) Engagement and Service Records, 1903–1911, contain details of approximately 1,700 Australian and New Zealand sailors during the period after Federation and immediately before the formation of the Royal Australian Navy. It consists of 41 folders of forms for engagement or re-engagement in the Royal Navy and two large bound volumes of personnel service records. The engagement forms for each individual serving in the Australian Naval Force (ANF) between 1903 and 1911 includes the following information:

- The ships they served on

- Date and place of birth

- A personal description including trade or occupation and scars and tattoos.

- A note on any previous service history

The Memorial plans to digitise the engagement and re-engagement forms, and to make them available on the Memorial’s website in the near future.

Private Records

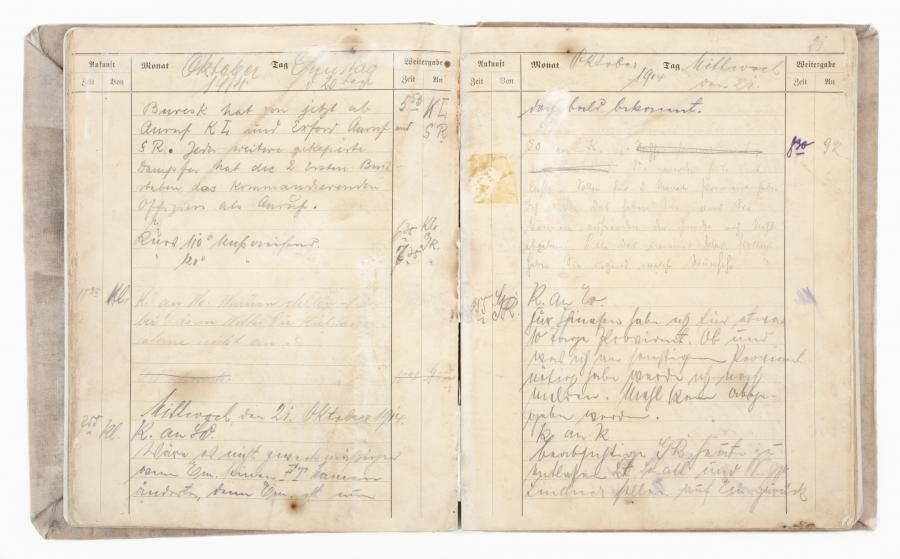

There are numerous records in the Memorial’s collection which provide details on the daily tasks and duties of early naval personnel and also on the movement of early Australian vessels. Some collection highlights include:

- PR03295 – Little, Vivian Agincourt Spence (Chaplain)

- 1DRL/0669 – Seabrook, John William (Leading Signalman, HMAS Sydney I)

- PR02076 – Gedling, Stanley Alfred (Leading Signalman), 1894–1969

- Numerous records relating to Captain John Glossop (HMAS Sydney) and Commander Rupert Garsia (HMAS Sydney) and the Sydney–Emden fight of November 1914.

Photographs and other items can be searched using the Memorial’s collection database:

Sea Power Centre

The Sea Power Centre is an independent research centre which aims to inspire and nurture development of maritime strategic thought by providing intellectual rigour to the public debate on maritime strategy and other maritime issues. It researches the history of the Royal Australian Navy and displays some of this history on its website:

Sources

Tom Frame, No pleasure cruise: the story of the Royal Australian Navy , Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2004

Arthur W. Jose, The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918., vol. 9: Official History of Australia in the war of 1914–1918, 9th ed., Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1941 (available on the Memorial’s website: /histories/first_world_war/volume.asp?levelID=67895)

David Stevens (ed.), The Royal Australian Navy: a history, vol. 3, The Australian Centenary History of Defence, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2001