The Simpson Prize 2020

The question

“Allied victory brought an end to war, suffering, and challenges for Australia and its people.”

To what extent do experiences of 1919 support this view?

Instructions

The Simpson Prize requires you to respond to the question above using both the Simpson Prize Australian War Memorial source selection (below) and your own research.

You are encouraged to agree with, debate with, or challenge the statement from a variety of perspectives – individual, national, and global – and to use sources in a variety of forms.

You are expected to make effective use of a minimum of three of the sources listed below. Up to half of your response should also make use of information drawn from your own knowledge and research.

Information about word or time limits, the closing date, entry forms, and judging can be found at the Simpson Prize official website.

Note: students who submit winning entries for this year’s Simpson Prize question will travel in 2020.

The competition is funded by the Australian Department of Education and run by the History Teachers’ Association of Australia.

The sources

Source 1: Artwork

Vida Lahey, Rejoicing and remembrance, Armistice Day, London, 1918, 1924. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C186262

The painting depicts groups of women mourning and rejoicing at St Martin–in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square, London, on Armistice Day, 11 November 1918.

Source 2: The John Monash address, 26 November 1918

“We are faced with the problem of returning to Australia something like 200,000 individuals – comprising fighting men, munitions workers, and dependants (wives and children). The problem is not only how to return these people home to Australia in the most expeditious way, but also how to send them home in a condition – physically, mentally and morally – to take up their duties of citizenship with a minimum of delay, a minimum of difficulty and a minimum of hardship on the community and on the individual …

To do that we have to begin creating a morale throughout the AIF – a morale which, for want of a better word, I will call the “reconstruction morale” …

[A]t what rate shall we be able to send the men home? That depends on the shipping available, and there will be a very heavy demand by all nations, and for all purposes, on all available tonnage. That is an Imperial question; in fact, it is an international question. Great Britain must be prepared to take her share of tonnage, and the Shipping Control will allot certain proportions to Australia. Our position is likely to be relieved by the necessity … of bringing from Australia to England a great amount of wool, wheat and meat …

We have also to consider the capacity of Australia to absorb the men, for it would be a great disaster to have dumped in Australia 200,000 men who were either without employment themselves, or who would displace from employment those now employed …

What employment can be made available? We have Education, which will become part of the Demobilization Department, and will embrace:

- Commercial training.

- Preparing men for academic careers.

- University Courses.

- Professional or vocational training.

Then Industrial employment comprising:

- Commercial employment …

- Scientific employment.

- New apprenticeship …

- Men who have broken their apprenticeship, or whose term of apprenticeship has been arrested, and who wish to continue in their trade.

- Wage-earning in a man’s present trade.

- Learning of new trades: this is of special importance to Australia, who in future intends to open up new industries, such as tin-plate making, ship building …

- Agricultural and rural industries of many kinds …

- Commonwealth workshops. The Commonwealth proposes to establish workshops, stores, etc. …

In conclusion, I ask for the utmost co-operation on the part of every officer and man; for what I am setting out to do is to be attempted in the common interests of ourselves, our men and our country.”

Address on Repatriation and demobilization by John Monash to divisional and brigade commanders on 26 November 1918, pp. 19–20, 24–25, 30. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1341638

Source 3: Film

Repatriation film, Repatriation Department, Australia, c. 1918. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/F00139

Source 4: Quote

“I know of at least one Aboriginal veteran of World War I who was not only denied his pay packet and his pension, but upon his return was given the very same rags he had been wearing the day he volunteered, and sent back to work on a station, as if the trenches and mud and the fighting had never happened.”

Gracelyn Smallwood, “The injustices of Queensland stolen wages”, in "Your say", Koori Mail, Issue 424, 23 April 2008, p. 25.

Source 5: Quote

“Yet before the last veterans reached home the cheers were already dying away, and it soon became clear that the soldiers’ rewards would be less than had been promised during the war. Worse, ‘when I got home in 1919 Ex Diggers were singing for a living in the streets. Men without arms and legs, some in wheelchairs’ [H. Brewer reminiscing in 1967]. Probably that was not common in 1919, but it became more so with time, as stay-at-home Australians, weary of war, recoiling from its horror, and sickened by the number of victims, tried to forget those tragic years as quickly as possible. They could continue in ways and occupations they had not quit, and they easily resumed pleasures and relaxations the war had caused them to abandon. They were unable or unwilling to comprehend either the magnitude of the soldiers’ ordeal, or the force of the memories, good and bad, which separated returned men from others. They wanted a return to normalcy, and they expected returned men to show a similar desire.”

Bill Gammage, The broken years: Australian soldiers in the Great War, Melbourne University Publishing, Victoria, 2010, p. 275.

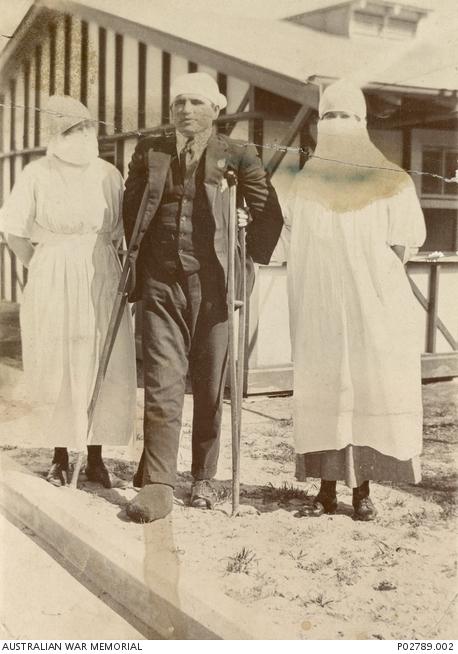

Source 6: Photograph

Voluntary Aid Detachment nurses M.M. Brooks and “Smithy” with a recovering soldier outside the flu ward at the Randwick Military Hospital, 1919. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C362415?image=1

Source 7: Statistical data on deaths in the Australian Imperial Force

|

Year |

From battle casualties |

From non-battle casualties |

Total |

Progressive total |

|

1914 |

- |

14 |

14 |

14 |

|

1915 |

7,819 |

655 |

8,474 |

8,488 |

|

1916 |

12,823 |

873 |

13,696 |

22,184 |

|

1917 |

20,628 |

1,108 |

21,736 |

43,920 |

|

1918 |

12,553 |

1,687 |

14,240 |

58,160 |

|

1919 |

27 |

597 |

624 |

58,784 |

|

1920 |

- |

6 |

6 |

58,790 |

|

Totals |

53,850 |

4,940 |

58,790 |

58,790 |

From A.G. Butler (ed.), Special problems and services, vol. III of The Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914–1918, Australian War Memorial, Melbourne, 1943, p. 900.

Source 8: Photograph

Sergeant James Matthews, 7th Battalion, and his British bride, Caroline Janetta (nee Huggett), on their wedding day in London, 13 April 1918. Matthews later returned to Australia with his wife on 25 February 1919. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1028878