Bravery under fire

In the days leading up to AnzacDay 1995 a small group of Australian troops displayed a special kind of bravery. While working at the Kibeho refugee camp in southern Rwanda, they witnessed the Rwandan army carry out a revenge attack on Hutu refugees, some of whom had taken part in the Rwandan genocide of the previous year. The Australians could not stop the massacre, but they courageously continued to work under fire to save as many civilians as possible.

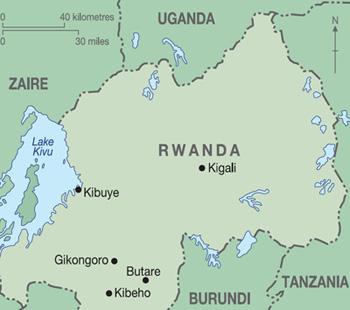

A small, mountainous country in central Africa, Rwanda is populated mainly by two ethnic groups: the minority Tutsi and the majority Hutu. When the Belgians ruled Rwanda the Tutsis held a privileged position. When the country became independent in 1962 the Hutus gained power, and many Tutsis were forced to flee to neighbouring Uganda.

In April 1994 negotiations to end a Hutu–Tutsi civil war broke down when the president of Rwanda, who supported the peace plan, was assassinated. Hutu extremists then perpetrated genocide on Tutsis and moderate Hutus. Half a million Rwandans were killed in a little over three months. At Kibeho, as throughout the rest of the country, the Hutu militia attacked the village church, blasting holes in the walls with rocket-propelled grenades and murdering about 3,000 people who had sought sanctuary inside.

Innocent people were dying in their thousands, but the international community did nothing. The genocide ended only because the Tutsi rebel army, the Rwandese Patriotic Front, defeated the Hutu government and took power in July 1994.

An Australian peacekeeper stands amid the remains of Kibeho camp two weeks after the massacre, May 1995.

Eventually the United Nations (UN), which had retained a small mission in the country during the genocide, established a new expanded UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), and the Australian government, after long deliberation, decided to provide the medical contingent along with an infantry company to provide security. The Australian component of UNAMIR arrived in Rwanda in August 1994 (see Wartime 27).

In February 1995 the first Australian contingent completed its tour and was replaced by another. Although the civil war had ended more than six months previously, hundreds of thousands of “internally displaced persons” (IDPs) – refugees who had not crossed an international boundary – were still living in camps in southern Rwanda. The largest of these was Kibeho, which sprawled over nine square kilometres and held between 80,000 and 100,000 people.

The new Tutsi government believed the camps were sheltering many people who had taken part in the genocide, and feared the camps could become the base for a Hutu guerrilla army. After the United Nations had been unable to persuade the refugees to voluntarily return to their homes, the Tutsi-controlled Rwandan army began planning a military operation to close the camps by force.

On 18 April about one thousand Rwanda army troops arrived at Kibeho to shut down the camp. The UN mission, taken by surprise by the Tutsi government’s action, hastily requested the Australian contingent put together a force consisting of a medical section with an infantry platoon. Early the next morning it left for Kibeho with orders to provide medical assistance to the refugees before they began their journey home.

When the Australian convoy reached the massive camp it drove past abandoned shelters, discarded possessions, and smouldering campfires, and many wondered where all the people had gone. The answer came when they reached the hill above the church and found that the Rwandan army troops had herded the entire camp population into an area 1,000 metres long and 500 metres wide on the ridgeline below. One Australian soldier compared the scene to a football crowd, another to cattle crammed into a feedlot.

The Australians made contact with the UN force already at Kibeho, a Zambian infantry company, and then with the Rwandan army, which limited the medical team to only briefly treating the refugees once they exited the camp. Before the people could reach the Australians, they had to pass through a checkpoint where genocide survivors pointed out individuals who had taken part in the killings. Rwandan soldiers would arrest these men and women and take them away, presumably for execution. Each evening the Australians left Kibeho, but the Zambian troops remained in the camp overnight.

On 22 April the Australians arrived at Kibeho to find that many of the refugees had been killed or wounded during the night. About half of those injured had gunshot wounds inflicted by Rwandan soldiers; the other half had machete wounds from Hutu militia members who were trying to terrorise the refugees into remaining in the camp, so as to provide the militia with a “human shield”.

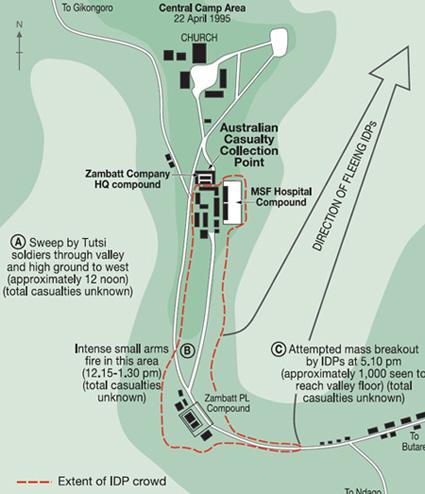

This map, based on an Australian Army map of the incident at Kebeho, shows the Zambian (Zambatt) compounds and the path taken by the fleeing refugees (IDPs).

The wounded were being treated at a hospital run by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF – Doctors Without Borders), so the Australians set up their medical station there. While the medics worked on patients, the infantry went out with stretchers to retrieve more casualties. At about 10 am shots were fired towards the hospital. In response, Lieutenant Steve Tilbrook, the Australian infantry commander, moved the Australians to the Zambian company compound for protection.

Shortly after, in heavy rain, the Rwandan troops moved into the hospital compound and started shooting. The refugees stampeded. Some tried to break out of the camp but were hunted down in the valley by troops forming an outer cordon. Others surged over the razor wire barrier surrounding the Zambian position and swamped the compound. Lance Corporal Andy Miller was knocked over by the rush and separated from his infantrymen. After being hit by a stick and a rock, and having to brandish his Steyr assault rifle to ward off further attacks, Miller got back to his men. They then fixed bayonets in case they needed to defend themselves, the first time Australian infantrymen had done so since the Vietnam War.

Despite the gunfire and stampede, the Australian medical team, led by Captain Carol Vaughan-Evans, continued to work, using a sandbag wall and a truck for cover. When calm returned, the Australians were required to remove all able-bodied refugees from the compound, but the medics and infantrymen were also able to collect the wounded and evacuate 25 seriously injured patients by helicopter to hospital. One of these was a small boy named Buregeya, whom Vaughan-Evans recalled was “just riddled with shrapnel and bullets”, but despite this managed to survive his wounds.

The staff from the MSF hospital had escaped to the Zambian compound and told Tilbrook that there were some doctors still in the building. Tilbrook and two soldiers ran to the hospital, crossing a large open area as Hutu militia and Tutsi-government soldiers traded fire. The Australian officer found the French doctors and took them back to the Zambian compound. Later, a panicked MSF doctor told Tilbrook that another person was still in the hospital. Tilbrook went out again with two more soldiers, found the woman hiding in a cupboard, and returned safely.

After the Kibeho massacre, the Australian Medical Support Force returned to the camp to treat sick and wounded refugees, May 1995.

As the medical evacuation helicopters took off at about 5 pm, Australians on board saw at least a thousand refugees rush out of the camp. The Tutsi troops stood on the ridges and fired down on them with automatic rifles, rocket-propelled grenades, and a .50-calibre machine-gun. The soldiers then moved through the valley in the still-pouring rain, bayoneting or shooting the wounded.

As the rest of the Australians prepared to leave Kibeho that night, SAS medic Trooper Jon Church (who would later be killed in the 1996 Black Hawk training accident) found a bawling three-year-old girl and decided to rescue her. Another medic bandaged her arm to make it appear that she was injured, and she was given a biscuit laced with Diazepam. When the sedative put her to sleep, she was hidden in one of the ambulance storage bins and taken to an orphanage. As Vaughan-Evans later wrote, “We always remember that as a small victory. Despite all the [Rwandan army] did to that mass of humanity, we got one little girl out of there.”

That night, still shocked by the events of the day, the Australians camped at a small village just north of Kibeho. As Tilbrook later wrote, they had been placed in an impossible situation: “We didn’t like what was happening, but we knew that we couldn’t do anything to stop it. What we could do, though, was help as many of the wounded as we could.” If the Australians had opened fire at the Rwandan army, they would probably have been wiped out, and the Rwandan government would certainly have demanded the immediate removal of the UN mission.

On 23 April the Australians returned to Kibeho to treat casualties and recover bodies. Warrant Officer Rod Scott of the medical section organised teams to move through the massacre site to count the dead. Pools of blood and drag marks indicated where Rwandan soldiers had removed bodies overnight, and the Australians were prevented from looking in huts and latrines where corpses could have been hidden. In the areas of the camp to which the Australians had access, they counted 4,050 dead. Both UN and Rwandan government reports minimised the numbers killed. A senior UN military officer visited Kibeho that day and decided that 2,000 people had lost their lives; the Rwandan government later claimed that only 330 had died.

The Kibeho massacre was a horrific and disturbing event for all members of the Australian contingent in Rwanda. Many would later be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Four who served at Kibeho – Corporal Andy Miller, Warrant Officer Rod Scott, Lieutenant Steve Tilbrook, and Captain Carol Vaughan-Evans – were awarded the Medal of Gallantry for their actions, the first time Australian soldiers had been awarded gallantry medals since the Vietnam War.

Further reading:

- Narelle Biedermann, Modern military heroes, Random House Australia, Milsons Point, NSW, 2006.

- Peter Londey, Other people’s wars: a history of Australian peacekeeping, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2004.

- Linda Polman, We did nothing, Penguin Books, London, 2004.