A devastating tally

The redevelopment at the Australian War Memorial allows objects from the National Collection to be seen in a new light, and to offer a different perspective. One such object, on display for more than fifty years, is the right-hand vertical stabiliser of a Messerschmitt Bf 110G. This metal tail fin, 1.4 metres tall, is grey aluminium stencilled with 121 small Royal Air Force (RAF) roundel emblems. Below each roundel is a silhouette of a four-engined bomber, and below that, the date of each victory. The Messerschmitt was flown by Major Heinz Wolfgang Schnaufer, the most successful German night fighter pilot of the war, with 121 kills against Allied bombers in only 164 operational sorties. For decades this object has been viewed as little more than a curiosity, recording the impressive scorecard of a highly skilled pilot.

Starboardi fin of 3C+BA. Schnaufer flew a number of Bf 110s in combat. All were emblazoned with his tally. 3C+BA was not his favourite fighter; that was G9+EF, shot down on 30 March 1945. Soon after the war 3C+BA was flown to England for specialist examination. The other half of the Memorial’s tail, the port fin, is displayed at the Imperial War Museum, London.

The tally on the tail fin is certainly astonishing and the fin is an extraordinary object. In one devastating night on 21 February 1945 Schnaufer claimed nine Lancasters – two in the early hours of the morning and a further seven that night in just 19 minutes. But the fin also represents the loss of more than 800

lives and 121 heavy bombers. It is important we do not forget the people and the motivations for these actions; behind the stencils of bombers lie more than 800 stories.

Research is ongoing, but at least 47 Australians were among the 815 who crewed the bombers accounted for by Schnaufer. Killed over a three year period, these Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) crew came from different backgrounds and different squadrons; they flew in different aircraft, attacking different targets. They are united by one terrifying experience – a shared story of attack, fire, and for almost all, a violent death. Here follow a few of the stories behind Schnaufer’s victories, and what each meant for the fliers and their families.

Deadly tactics

The career of 21-year-old Heinz Wolfgang Schnaufer coincided with the onset of the most intense phase of the Royal Air Force’s bombing campaign against Germany. In the spring of 1943, some Messerchmitt 110s were fitted with twin vertically-firing cannons that became known to the fliers as schräge Musik. (Schräge means ‘sloped’, referring to the upward angle of the guns; but in popular culture schräge Musik was also slang for dissonant or ‘weird music’.) This innovation had a devastating effect in the battle of the night skies as Schnaufer mastered the technique. Once his radar operator had located the bomber stream, Schnaufer would select a target aircraft, fly underneath – as close as 30 metres – into the blind spot beneath the wing, undetected and out of range of the bomber’s gunners, and fire upwards into the bomber’s fuel tanks.

Schräge Musik accounted for Flight Sergeant Bede King’s Lancaster on 16 December 1943; on his third operational flight, Air Gunner King was shot down en route to Berlin. His No. 49 Squadron Lancaster exploded over a swamp, killing all the crew. It was the 39th Allied bomber shot down by Schnaufer.

Flying Officer Arthur Nash from Perth was still with an Operational Training Unit (OTU No. 27) when he was killed on his very first operation. Nash was the pilot of a Wellington detailed to bomb Düsseldorf when it was shot down by Schnaufer near Brussels on 1 August 1942. Nash and his four crewmates – all Australians – were killed: navigator Sergeant Owen Morgan, a cadet draftsman from outback Queensland; 21-year-old Sydney postman Sergeant Charles McKee; Tamworth solicitor Sergeant Daniel O’Halloran; and linotype mechanic Sergeant Clifford Luedeke.

Another man shot down the same night was pilot Flying Officer Geoffrey Silva DFC of No. 24 OTU Squadron. Silva survived, managing to escape the burning Whitley and to parachute safely to the ground. Making his way across Belgium and France he evaded capture for three weeks, got to Gibraltar and returned to England. He then transferred from Bomber to Coastal Command (No. 210 Catalina squadron) and was killed during a submarine patrol over the Bay of Biscay on 13 June 1943.

Directed to attack Saarbrücken (in a diversion from the main target, Nuremburg) Sergeant John Marshall, the pilot and only Australian in a No. 78 Squadron Halifax crew, was shot down by Schnaufer over Brussels early on 29 August 1942. Bombing by the 113 bombers was inaccurate and the raid was not a success. Marshall’s crew of seven from several nations are buried in a churchyard cemetery near Tombeek.

Reality

The following year, a RAF investigation into the death of South Australian Pilot Officer Stanley Allan and his crew describes their bodies as having been ‘carbonised’ when their No. 218 Squadron Stirling was shot down after attacking Wuppertal near Düsseldorf. Allan was the pilot and sole Australian in the bomber crew. He was identified by scraps of his battle dress, braid and a pilot’s brevet. On 30 May 1943 Flight Sergeant William Davis was shot down by Schnaufer as he piloted his Stirling to raid an aircraft adhesive factory in Wuppertal. His No. 218 Squadron crew’s remains could not be individually identified, so they were concentrated into three coffins. Formerly a pharmaceutical chemist from Launceston Tasmania, Davis left behind a widow, Meryl.

On 20 October 1943, after their No. 405 Squadron Lancaster was hit by Schnaufer, pilot Flying Officer Kemble Wood’s aircraft exploded. The casualty report recorded that “pieces of bodies, legs, arms etc were found on the ground and hanging in trees.” None of the crew could be individually identified so they were buried together in a collective grave. In late May 1942, Flying Officer Wood had taken part in the historic thousand-bomber raid on Cologne, as well as the first raid on Peenemünde, the German scientific research centre where the Nazis were developing V-weapons. He had completed 19 operations with the elite Pathfinder Force and was newly married. The day before his death had written his 98th letter to his wife Ethel.

The 34th aircraft on Schnaufer’s tally included Air Gunner Flight Sergeant Stanley Kitchen. Homeward-bound after bombing Kassel on 22 October 1943, his No. 57 Squadron RAF Lancaster was coned by searchlights and shot down. The only Australian in the crew, he could only be identified for burial by the laundry mark on his shirt collar. Kitchen’s mother, Viola, was still writing to RAAF Headquarters in mid-1946 to discover her son’s place of burial. “The intervening years have been strain and anxiety, wondering his fate … it was his first flight and last flight over Germany … Victory has not brought peace of mind to us.”

Former clerk Flight Lieutenant Trevor Griffiths was 26 and had completed 11 operations with No. 622 Squadron. On 15 February 1944, after bombing Berlin and homeward bound, he was shot down by Schnaufer over the Zeider Sea. On fire, the wings dropped off and the Lancaster plunged into the sea. Flight Lieutenant Griffiths’ body washed up at Andijk three months later.

In the early morning of Anzac Day 1944, Jewish Australian navigator Flying Officer Adolf Hoffman, serving with No. 115 Squadron RAF, raided Karlsruhe and turned for home. Schnaufer’s 54th ‘kill’, Hoffman’s Lancaster went down in flames. His body was could only be identified by his uniform Australian shoulder flashes. Just out of school, Adolf had excelled in cricket, gymnastics, and athletics. At 15 he won every sprint event in the Queensland Junior Athletics Championship. In his final year of school he was awarded a bursary, given to “the boy proceeding from school to university who shall have been most distinguished for scholastic attainments, force of character, and proficiency in the outdoor sports of the School”.

Adolf Hoffman had been enrolled in Economics at the University of Queensland for six months when he left his studies to join the RAAF. In the months that Hoffman was listed as “missing believed killed”, Hoffman’s father wrote to the RAAF, “We cannot accept the belief that such a fine, powerful and well armoured ship [Lancaster] would crack up in mid air to such an extent as to eliminate all hope.”

The following month Flight Sergeant William Gertzel of No. 466 Halifax Squadron was killed. This was Schnaufer’s 65th claim. Gertzel was part of a six-Australian crew on a mission to bomb railway and transport yards at Hasselt, Belgium. Buried in a communal grave, the six RAAF men and their British Flight Engineer were not declared dead for well over a year. The mother of the Australian Bomb Aimer, Harold John Smith, wrote achingly polite and respectful letters to the Air Ministry asking for news. When Smith and the crew are officially declared dead in September 1945 Mrs Smith wrote “the 17 months of suspense has been awful and although the blow is hard it is much better to have some definite news.”

Flight Sergeant Malcolm Graydon, a Melbourne grocer’s assistant, was the only Australian in his No. 76 Squadron Halifax crew. Homeward bound after bombing Aachen, they were shot down over the Netherlands on 25 May 1944, Schnaufer’s seventy-second victory.

Not only airmen

Although the Memorial is investigating Australian casualties, it is important to remember that many airmen from other nations were also killed, as well as civilians on the ground. On the night of 30 January 1944 Allan Hart and Harold Boal of No. 97 Squadron RAF, two country boys flying in Lancaster JB659, were shot down. When their aircraft was attacked by Schnaufer, the cockpit, blasted with cannon fire, separated from the fuselage and plummeted to earth with Hart and his Canadian bomb aimer Gordon Williams inside. The rest of the aircraft, with the two port engines still running, crashed into a farmhouse west of Amsterdam, and burst into flames. As well as all the crew, six members of the Van der Bijl family, asleep in their home, were killed. The bodies of Hart and Williams were recovered; but the force of the crash drove the Lancaster 26 feet into the earth, taking the rest of the crew with it.

Allan Hart was the only son of Norman and Ruby of Murrumburrah, New South Wales. After school and Agricultural College, Allan Hart intended to take over the family farm. But war broke out and Hart enlisted in the RAAF, aged 20. After nearly two years’ training, Hart teamed up with his navigator, 20-year-old Flight Sergeant Harold Boal from Echuca. Their first operational squadron was 463 Squadron RAAF, and later 97 Pathfinder Squadron RAF. The entire crew were killed 22 days into their second tour. Allan Hart must have had a premonition, because on the day of this operation he wrote to his mother, “It’s curtains for me tonight.”

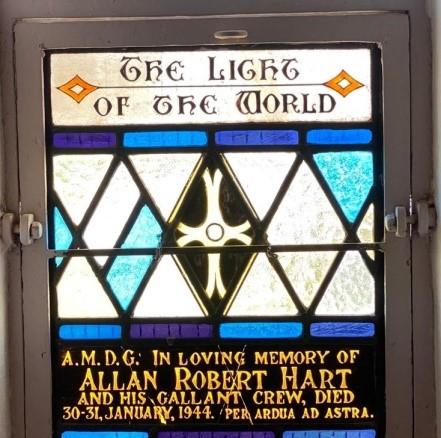

After the war a RAF investigation team recorded 2,210 pieces of wreckage from the crash, strewn over a wide area. The holes in the ground made by the engines were clearly visible, and the large impact crater had turned into a lake. Allan Hart’s parents never got over his death. Indeed they installed a stained glass window in St Paul's Anglican Church, Murrumburrah, New South Wales, in memory of their only son.

The Allan Hart Memorial Window inside St Paul’s Anglican Church, Murrumburrah

Other costs

First and foremost, the Schnaufer tail fin’s tally represents social, personal and emotional cost. But it also represents enormous economic loss. The strategic air offensive against Germany was the longest and largest single air campaign of the war and consumed an extraordinary quantity of resources, both human and economic. In total, 815 aircrew were shot down by Heinz-Wolfgang Schnaufer. Of these, 760 or 93% of the men lost their lives (not including civilian deaths on the ground resulting from crashes) and 61 men were taken as prisoners of war. Six downed airmen managed to evade and return to the UK.

The cost of training a single airman during the Second World War was £10,000 and it took two years, so the training alone of the ‘Schnaufer victims’ cost £8,150,000 in 1940s money. The tail fin tally represents the loss of not just lives, but also 121 aircraft, 121 loads of fuel, bombs and ammunition. A very conservative estimate of the cost that Schnaufer’s tail fin represented in 1945 was nearly £13 million. Roughly converted, that is AUD 932,530,000 in today’s money.

This does not include a myriad of things – the thousands of men and women who supported air crew and flying operations, airmen’s wages, accommodation, meals, clothing and equipment, the cost of establishing and caring for war graves, the outlay of pensions. The tail fin represents an enormous waste of materiel and effort. But more than anything, the tail fin represents the cost in human lives resulting from the work of a single skilful night fighter pilot. The kill tally represents 815 airmen who left behind wives, mothers, fathers and families across the world, from London and Liverpool, to Auckland and Toronto, to the small town of Murrumburrah.

From the German point of view, Schnaufer’s actions, skill and tally were entirely justifiable. The huge number of Allied bombers scattering nightly bombs caused immense destruction and terrible attrition on the ground. Whatever its place in history, the Australian War Memorial’s Schnaufer tail fin is an object that invites deeper thought.

Germany, June 1945. A Halifax crew of No. 462 Squadron with Schnaufer’s “back-up aircraft” 3C+BA. This tail fin is held at the Imperial War Museum; the AWM’s starboard fin is out of frame.