The Simpson Prize 2022

To what extent have the Gallipoli campaign and the Western Front overshadowed other significant aspects of Australian’s experience of the First World War?

Instructions

You are encouraged to debate, agree with, or challenge the question.

You are expected to use at least four sources listed below. Up to half of your response should use your own research.

Information about word or time limits, the closing date, entry forms, and judging can be found at the Simpson Prize official website.

The Simpson Prize is funded by the Australian Department of Education and run by the History Teachers’ Association of Australia.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people please be aware that this resource may contain images and names of deceased persons.

The sources

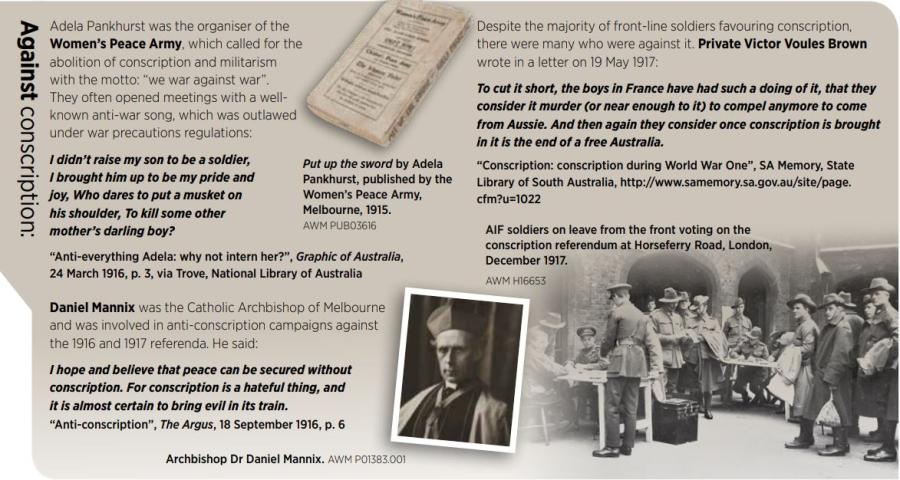

Source 1: The anti-conscription debate, presented on an Australian War Memorial resource, 2017

View the full resource here: https://www.awm.gov.au/sites/default/files/awm-poster-2017.pdf

Source 2: Extract from Janice N. Brownfoot, “Goldstein, Vida Jane (1869–1949)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/goldstein-vida-jane-6418

Of the Australian women connected with the emancipation and suffrage movements of the day Vida Goldstein was the only one to gain a truly international reputation. In February 1911 she visited England at the invitation of the Women’s Social and Political Union and her speeches drew huge crowds. Alice Henry wrote that Vida “was the biggest thing that has happened to the woman movement for some time in England”.

During World War I Vida was uncompromisingly pacifist. She became chairman of the Peace Alliance, formed the Women’s Peace Army in 1915, and was involved in much valuable social work including the organization of a women’s unemployment bureau in 1915-16 and a Women’s Rural Industries Co. Ltd. In 1919, with Cecilia John, she accepted an invitation to represent Australian women at a Women’s Peace Conference in Zurich: she was away three years. This trip signalled the end of her active public involvement in Australian feminist and political work: the Women’s Political Association was dissolved, the Woman Voter ceased publication and Vida turned her attention increasingly to promoting more general causes, particularly pacifism and an international sisterhood of women.

Source 3: Extract from Wes Olson, “The Men Behind the Guns”, Wartime 89, 2019. p. 48. The full article examines HMAS Sydney’s battle with the German Light Cruiser SMS Emden on 9 November 1914.

Boys Become Men.

The unsung heroes were Sydney’s 15 boy sailors. After the battle, Captain Glossop cleared the lower deck to thank officers and men for their efforts. He especially wished to acknowledge the work of the boys, some of whom had only recently joined the ship. Glossop said that they had borne their baptism of fire coolly and had performed splendidly.

Sixteen-year-old Boy 1st Class John Ryan had been tasked with keeping Sydney’s forward gun supplied with ammunition. Emden’s guns fired fixed ammunition (the shell being fixed into the cartridge case); each cartridge weighed about 25 kg and was fairly easy to handle. Sydney’s guns fired separate ammunition, comprising a 45.3-kilogram shell and 14.5-kilogram cordite charge. Ryan’s job entailed carrying the 6-inch shells from the forward ammunition hoist to the gun. The shells weighed nearly as much as Ryan, and after nearly an hour of action he was seen to be ”tiring somewhat”. According to Able Seaman James Stewart, RN, ”He could just manage to carry the 100-pound projectile from the ammunition hoist to the gun, but he hadn’t the strength to heave it into the gun”. Ryan nevertheless continued to deliver shells to the gun, whereupon the officer-in-charge took the projectile and loaded the gun.

Source 4: A film, “With the forces on the Palestine front”, James Francis Hurley, Palestine, 1917. AWM F00042

Source 5: Semakh Diorama and caption, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 2021

Wallace Anderson (1888–1975); Louis McCubbin (1890–1952); Alexander McKenzie (b.1971), Semakh diorama, (diorama: 1926–27, mixed media, 444 x 370 cm; background: 2013, oil on canvas on timber and metal support, 300 x 1000 cm) AWM ART91119.

Semakh was a small mud village on the southern end of Lake Tiberias (the biblical Sea of Galilee) that served the important Haifa–Damascus railway. Turkish and German troops had been sent to reinforce the small local garrison, and they turned the village and its stone railway buildings overlooking the open plains into a strong defensive position. With the British advancing on Damascus, it was important that Semakh be captured. The task fell mostly to the 11th Light Horse – a regiment of South Australians and Queenslanders with a noticeable number of Aboriginal troopers.

Advancing by moonlight in the early hours of 25 September 1918, the Australians came under machine-gun fire. The order was given: “Form line and charge the guns.” With swords drawn they rode into the fire. Once in the village, they dismounted and went in with bayonets. The enemy fought stubbornly, and many were killed. The capture of Semakh cost the Australians 43 killed or wounded. Of the 364 enemy prisoners taken, 150 were Germans.

Source 6: Photograph showing a wounded soldier being assisted by two Voluntary Aid Detachment nurses, who are wearing masks to protect themselves against the Spanish Influenza, New South Wales, 1919. AWM P02789.002

Source 7: Extract from Peter Monteath’s Captured Lives: Australia’s Wartime Internment Camps, National Library of Australia Publishing, Canberra, 2018, p. 99.

In time, above all else, it would be the performance of Australian forces on the battlefields of Turkey and the Western Front that would figure most prominently in Australian memory of the war. The challenges of the home front, while they shaped many lives, receded quietly into the past. As for German concentration camps [internment camps for Germans in Australia], though many knew of their existence, they were never a topic of open discussion or debate. With most of their prisoners dispatched from Australia’s shores after the war, that would never change.

Australia, though, had changed. While both before and after Federation it had been resolutely committed to the ideal of a White Australia, it had tolerated and even encouraged the arrival of Europeans from non-British backgrounds. The multiple contributions of such people had been at least quietly acknowledged, even celebrated. But the Australia that emerged from the First World War not only remained as resolutely committed to a White Australia as ever, its vision of its present and its future was more narrowly “British” than ever before. For years, German immigration was not welcome. As for Germans who remained, as they recovered from the traumas of war, many would have wondered what their fate might be should history repeat itself.

Source 8: Table showing “Australian military deaths during the First World War”

Data from: Australian War Memorial, First World War Official Histories, Volume III – Special problems and services (1st edition, 1943), Section V, pp. 896-897 https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1416942

|

Location |

Battle Deaths (killed in action or died of wounds, including as prisoners of war) |

Non-Battle Deaths (died of illness or other causes, including as prisoners of war) |

|

Gallipoli |

7,818 |

600 |

|

Western Front |

44,766 |

1,872 |

|

Prisoners of War: Germany |

267 |

70 |

|

Middle East |

973 |

590 |

|

Prisoners of War: Turkey |

21 |

39 |

|

United Kingdom |

4 |

1,249 |

|

Australia |

34 |

1,431 |

|

New Guinea |

6 |

64 (includes 35 on submarine HMAS AE1) |

|

HMAS Sydney |

4 (during battle with SMS Emden) |

|

|

At sea |

|

412 |

Additional statistics from:

Australian War Memorial, Statistics, military, https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/statistics_table#casualty

Australian War Memorial, HMAS Sydney, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/U50821

Australian War Memorial, The mystery of the AE1, https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/mystery-of-the-ae1

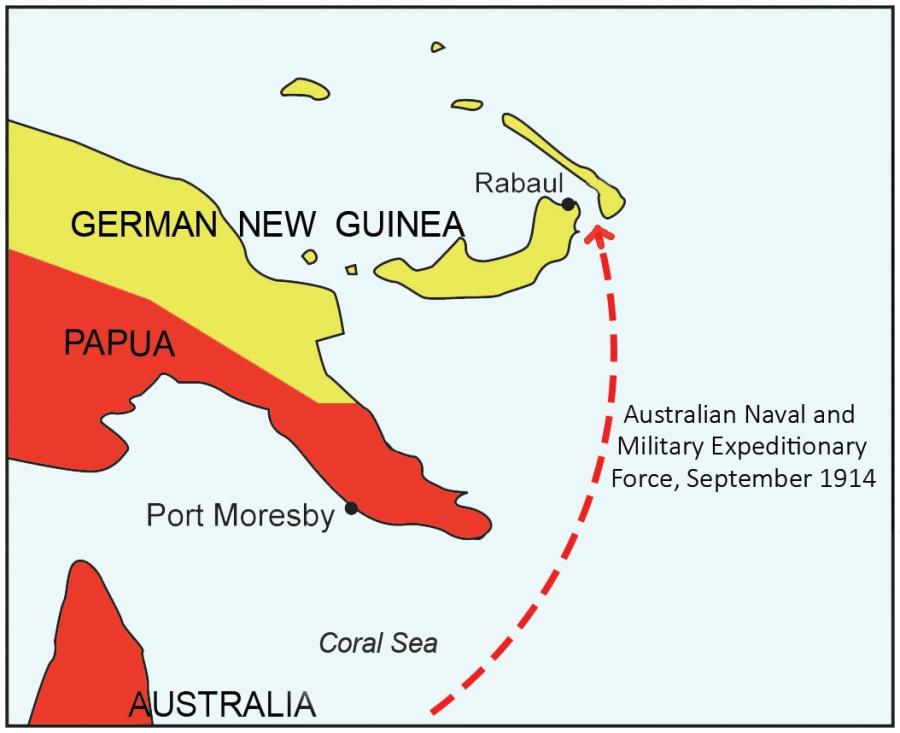

Source 9: Map relating to Australia’s first military engagement of the First World War

Enemy on the Doorstep

Germany held a string of colonies in the Pacific and, once the war began, Japan, Britain’s ally, was quick to occupy those above the equator. Similarly, a hastily arranged force called the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) was sent to seize German New Guinea.

The German Pacific colonies, established from 1884, were seen as a strategic threat to Australia. In their first actions of the war, Australians made landings at Herbertshöhe, Kabakaul, and Rabaul … There was comparatively little resistance, although six Australians were killed. A greater tragedy was the loss of 35 lives when the Australian submarine AE1 disappeared while patrolling off the New Guinea coast on 14 September. After the war Australia was given a League of Nations mandate over New Guinea; Papua New Guinea received its independence in 1975.

Australian War Memorial, 2021