“We got 1,500 ex-POWs away”

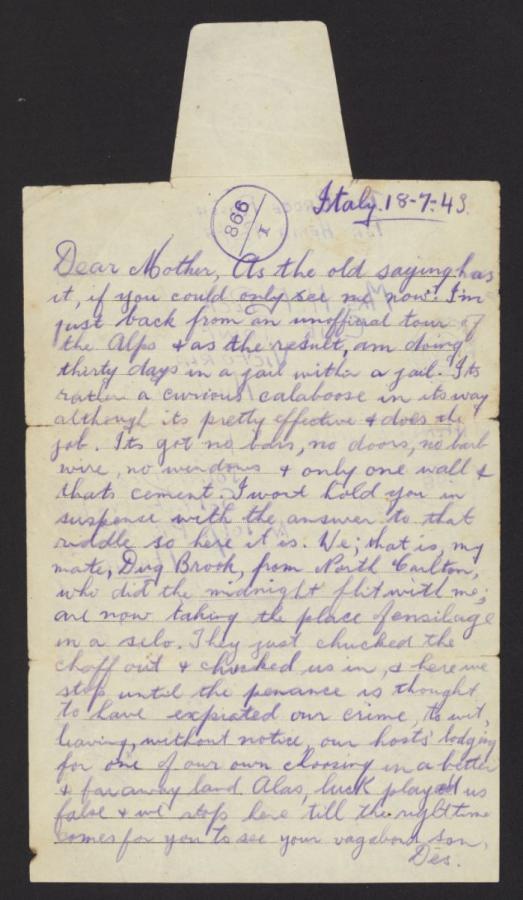

On 1 June 1942, exactly one year after missing the final evacuation ship from Crete, John Desmond Peck landed at Bari, Italy as a prisoner of war. Over the next three years Peck attempted several successful and unsuccessful escapes and formed a resistance group to help hundreds of other prisoners of war to escape to Switzerland. Peck’s survival in Italy depended on finding the balance between caution and action; navigating whom to trust, when to act, and when to hide.

Peck found that in Italy “half the people you trusted betrayed you, and you were back in the bag or you were shot”. There was no way of knowing who was friend or fascist.

Peck escaped the San Germano prison camp after a year of incarceration on 13 June 1943. When he reached the Swiss border three weeks later he had not eaten in three days. Starving and with only “snow and ice” for miles, Peck made the difficult decision to return to Italy. Desperate, he accepted an offer from a shepherd to bring him food. But instead of food the shepherd brought “a posse” and Peck was arrested and returned to Vercelli.

September 1943 brought about Peck’s 5th prison escape of the war. This time he was broken out of prison by comrades with the signing of the Armistice of Cassibile, between (most) Italian fascist forces and the Allies.

Hiding in town Peck soon swapped his uniform for civilian clothes. Having spent almost a year hiding in the hills of Crete, Peck had developed skills in evasion. With this in mind, he assembled “the first liberation and resistance committee in that province” to feed and clothe escaped prisoners of war.

After a month of operation, Peck shifted the committee’s focus to helping prisoners of war cross into Switzerland. By the end of October they were “getting out an average of sixty to seventy prisoners of war a week.” In his official report to the Australian Army, Peck described the system:

“An agent would contact three or four POWs in his area and take them by train to an appointed place. Three or four agents would meet with about ten or twelve POWs and they would hand them over to the zone agent who would take them by train to the Central Committee. We would then take them to the border.”

Peck divided his time between escaped prisoners of war and the local partisans. His agents started bringing supplies to the partisans at the border. Around this time Peck began sabotage missions:

Our most notable successes were the blowing of the Asino and Luino tunnels, the derailing of two troop trains, and five goods trains, the blowing of railway and road bridges, the destruction of the parachute factory at Cremenaga, the attack on the CEMSA armament works at Saronno, the abduction of enemy agents and spies and the wiping out of enemy outposts.

Vercelli local and committee member, Oreste Barbero, later told the story of his first meeting with Peck. One day “Gianni” came into his pastry shop, “told me about his activities and suggested that I should assist him.” It took little persuasion before Barbero became an important member of the committee. But not everything went well.

Oreste and Esther Barbero with John Desmond Peck in Vercelli, Italy. AWM2021.22.67 41/100

Arrests began in January 1944, when members and contacts of the committee, including Barbero, were apprehended. A tribunal investigated the group’s actions and Barbero was sentenced to 27 years in prison. This was the harshest sentence the tribunal delivered. As repression continued, it became too dangerous to continue. Peck later wrote that although they had only operated for five months, “in all we got 1,500 ex-POWs away.”

Peck himself was then captured by the Gestapo and Schutzstaffel (the SS) on 12 February 1944 while at the house of his second-in-command, Oreste Ferrari.

In an unpublished, untitled manuscript about his experience in Italy, Peck details that night:

“I was a wreck. Half my teeth were smashed in, my lips were pulverised and cuts and wounds were all over my face, body and head. Blood was pouring from my mouth and nose, dripping off my chin and running down my neck. My eyes felt as if someone had gauged them out with a corkscrew, and my body was one great agony.”

With three tommy guns aimed at him, Peck found that he was no longer afraid. Realising the Germans had not found the pistol in his belt, Peck had a jolting change of heart. The executioners tensed to shoot; Peck thought, “I am not ready to die yet.”

At that precise moment an SS officer interrupted the execution. He had found an attaché case and demanded that Peck tell him about its contents. Refusing, Peck was taken to the German headquarters at Luino and tortured for three days and nights. On 16 February 1944, the day before his 22nd birthday, he was taken to Como for court-martialing.

Peck was sentenced to death for the second time.

His execution was now scheduled for 15 May 1944. Peck was sent to San Vittore prison in Milan to await his sentence. During the following three months, he spent 75 days in solitary confinement. As his execution loomed, Peck joined a group of prisoners of war awaiting death sentences, on a working party to defuse unexploded bombs. Though it was dangerous work, Peck “much preferred the danger outside to the dismal hopelessness of a cell.”

But as Peck’s exceptional luck would have it, the day before his execution, an air raid took place over the factory where Peck’s “execution platoon” was working. As the guards ran to safety, Peck ran in the opposite direction. By the day of his scheduled execution, Peck was in Intra and back in contact with his organisation. By June, he had crossed the border into Switzerland.

Although free in Switzerland, Peck’s war was not over yet. Here he was recruited by the underground resistance movement as a British Liaison Officer.

August 1944 saw Peck return to Italy with orders to “carry on as before” with “sabotage, espionage, organising and fighting”. By mid-September Peck was called to the United Command in Domodossola and informed that “they wanted an experienced officer to take over the command of the Central sector of the front to build defence lines there.”

Peck accepted this role and led his division of 30 officers and nearly 500 men through tank and artillery attacks, various battles – including Domodossola – and missions of defence and sabotage.

Four months out from the Allied victory in Italy, Peck was repatriated to England in January 1945. By March he had met and married Brenda Peck (née Bird) and was on a ship home to Melbourne, leaving his new wife behind. A year later Peck returned to England to attend the 1946 Victory March in London and re-united with his bride. He remained in England permanently, working for the English Electric Company in Stafford. Peck died on 9 January 2002, aged 79.

Peck’s daughter Barbara donated the collected papers relating to his service, including two unpublished manuscripts, ‘Captive in Crete’, and ‘untitled’, to the Australian War Memorial after his death.

The Memorial has digitised this collection [PR03098] and made it available online as part of the Memorial’s Digitisation Project. You may view the collection here.

This is the third and final article in a sequence detailing the heroism of Lieutenant John Desmond Peck. For the other articles in the series, please visit this page.