Great War nurses

I have never regretted that I took the notion into my head to take on nursing, for it has opened up opportunities that I would never have had.

Sister Jessie Tomlins

More than 3,000 Australian civilian nurses volunteered for active service during the First World War. While enabling direct participation in the war effort, nursing also provided opportunities for independence and travel, sometimes with the hope of being closer to loved ones serving overseas.

The Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) had been formed in July 1903 as part of the Australian Army Medical Corps. During the war more than 2,000 of its members served overseas alongside Australian nurses working with other organisations, such as the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), the Red Cross, or privately sponsored facilities.

A group of officers, nurses and men of the 3rd Australian Casualty Clearing Station.

The women worked in hospitals, on hospital ships and trains, or in casualty clearing stations closer to the front line. They served in locations from Britain to India, taking in France and Belgium, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. Many of them were decorated, with eight receiving the Military Medal for bravery. Twenty-five died during their service.

By war's end, having faced the dangers and demands of wartime nursing and taken on new responsibilities and practices, nurses had proved to be essential to military medical service.

The adventure begins for a group of Australian nurses departing in the troopship HMAT Euripides, Melbourne, May 1916.

Group portrait of the sick bay staff from the Australian hospital ship AMFA Grantala.

Four of the five Malcolm family siblings served during the First World War. This portrait was taken after their return home.

Two patients from the Glenelg Anzac Hostel in white painted cart wheel hospital beds in the grounds of the hospital with a group of nurses and probably two visitors.

Right from the start: Sister Claire Trestrail

No words can describe the awfulness of the wounds. Bullets are nothing. It is the shrapnel that tears through the flesh and cuts off limbs.

During the invasion of Belgium in 1914, Sister Claire Trestrail was one of three Australian nurses who joined the privately funded Auxiliary Hospital Unit in Antwerp. On the night of 8 October, under heavy artillery bombardment, Trestrail and her colleagues worked tirelessly to move their 130 French and Belgian patients to safety in the cellars of the Burchem Concert Hall – "three dirty little caves under the kitchen".

The next morning, with the city deserted and burning, the nurses frantically loaded their patients onto any available transport, with little thought for their own evacuation. Later in the day, they flagged down three British buses laden with ammunition, and escaped from Belgium after a hair-raising trip to the coast.

In Britain, news of the nurses' amazing escape quickly spread. Soon afterwards, Trestrail joined the QAIMNS and returned to the front.

Sister Claire Trestrail (seated) with a ward assistant and patients at the Auxiliary Hospital Unit in Belgium

Sister Trestrail was one of very few Australians to receive the 1914 Star with clasp, recognising her service in Belgium under enemy fire during the early months of the war.

Hospitals in Egypt

It is all too dreadful and every day we hear of someone we knew being killed or wounded.

Sister Alice Kitchin

By the end of 1914, around 300 AANS nurses had left Australia for Egypt. On the long sea voyage, they were kept busy assisting with vaccinations and operations, and training male orderlies. The nurses were posted either to the 1st Australian General Hospital (1AGH), established in the grand Heliopolis Palace Hotel in Cairo, or to 2AGH in Mena House, a former royal hunting lodge.

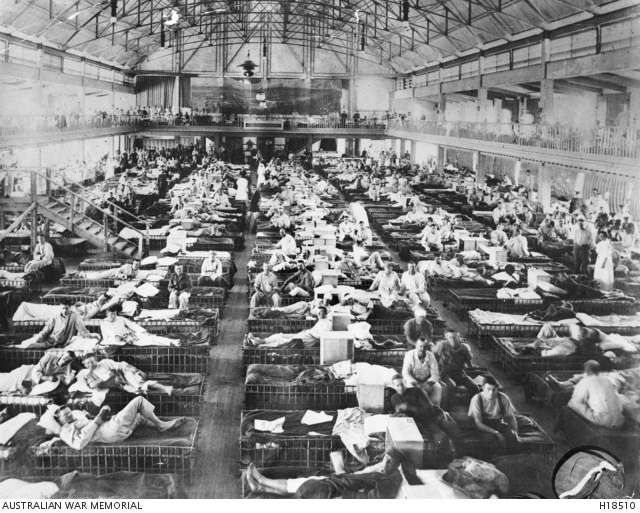

With the rapid influx of patients from Gallipoli in April 1915, the facilities were soon overcrowded, and equipment and supplies inadequate. Nursing staff worked around the clock. 1AGH took over a nearby amusement park, turning the ticket office into an operating theatre and the skating rink, scenic railway, and skeleton house into wards. Within three months it was operating as a 1,500-bed hospital.

Some of the badly wounded were returned to Australia on hospital ships, accompanied by nurses.

Temporary Matron Jean Miles Walker (centre front) with nursing staff of 1st Australian Stationary Hospital in Egypt.

In their time off, nurses engaged in souvenir-hunting or went on excursions to the pyramids. Socialising with officers was also popular.

From army nurse to midwife: Sister Nellie Morrice

The seventh of 11 children, Nellie Morrice enlisted in the AIF at the outbreak of war, as did four of her brothers. She was appointed head sister of 1AGH in Egypt in 1916. From Egypt she was sent to hospitals in Britain and France before joining 3AGH in Abbeville on the Somme in 1917. The following year, Morrice was awarded the Royal Red Cross 2nd Class for "valuable services with the Armies in France and Flanders".

On her return to Australia after the war, Morrice was involved for many years in the NSW Bush Nursing Association, specialising in midwifery and the care of infants.

Sister Morrice (right) with another nurse outside their tent at 3AGH in Abbeville, France, c. 1917.

Gallipoli: nurses close by

25-4-15 Red letter day. Gaba Tepe ... The wounded think the old ship is heaven after the peninsula. There are 557 patients on board and only 7 nurses.

Sister Ella Tucker

Wounded soldiers evacuated from Gallipoli arrive alongside the hospital ship Gascon.

Right from the landings on 25 April 1915, nurses cared for hundreds of casualties in the hospital and transport ships anchored off-shore. The wounded came in an endless stream, day and night, some barely able to walk, others on stretchers, shivering or unconscious through loss of blood. Medical supplies were limited and there was a desperate lack of fresh water. Despite the constant threat of Turkish shelling or torpedoes, the exhausted nurses cleaned, bandaged, warmed, and comforted their patients, many of whom had ghastly wounds or were suffering from the effects of gangrene and disease.

For the next nine months, soldiers were ferried to hospitals on the nearby Greek islands of Imbros and Lemnos, or transferred to Malta, Egypt, and Britain. Wards on the lower decks were crowded and poorly ventilated, and even simple nursing tasks were made difficult by the movement of the ship. Seasickness struck down nurses and patients alike.

Lemnos: order out of chaos

At first the situation on the island seemed hopeless. What could be achieved under such dire circumstances?

Sister Rachael Pratt

At the beginning of August 1915, during the Gallipoli campaign, 3AGH was landed on a bare and treeless hillside on the island of Lemnos. The tents and equipment were delayed for three weeks, water was in short supply, and there was no sanitation. Two days later, Matron Grace Wilson and 80 nurses arrived, closely followed by more than 150 patients from Gallipoli. Sister Pratt described the scene in her diary:

Things were in rather a state of chaos when the wounded began to arrive. Their dressings which had been applied on the hospital ships were saturated and covered in flies. Dysentery was a scourge on the island ... many of the wounded fell prey to the disease ... the cold weather brought frost-bitten patients. It was pitiable to see gangrene feet.

On arrival at Lemnos, the nurses were marched into camp, led by Matron Grace Wilson and Lieutenant Colonel James Dick.

When their tents and equipment failed to turn up, medical staff of 3AGH had to sleep rough.

The tent hospital presented new challenges for the nurses. They had to learn how to mend tears, re-hook walls, and manage guy ropes. And they were constantly at the mercy of the weather, with tents regularly blowing over.

Off-duty sisters socialise with naval officers on the deck of HMS Hazel.

In the summer months an early morning dip in Mudros Bay provided relief from the blistering Mediterranean heat.

"A woman of understanding": Matron Grace Wilson

Convoy arrived, about 400 – no equipment whatever – just laid the men on the ground and gave them a drink ... they are shattered and [we] have nothing to give them – no comfort whatever. All we can do is feed them and dress their wounds.

Matron Grace Wilson arrived on Lemnos in early August, just days after learning of the death of her brother, Graeme, shot by a Turkish sniper on Gallipoli three months earlier. As casualties began to arrive, she was appalled by the lack of equipment and conditions "too awful for words".

Leading by example, Wilson set about bringing order out of chaos at the tent hospital. Despite their own discomfort and the huge workload, the nurses persevered and within a month were treating over 900 patients. Sister Frances Selwyn-Smith wrote of Wilson's leadership: "At times we could not have carried on without her. She was not only a capable Matron, but what is more, a woman of understanding."

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Wilson was appointed Matron-in-Chief of the Second AIF; she served in the Middle East until illness forced her to return to Australia in 1941.

Other items in the collection relating to Matron Grace Wilson

The Western Front

Where there was life, there was hope, and we won.

Sister May Tilton

Over 80 per cent of Australian First World War battle casualties occurred on the Western Front. In order to deal with the thousands of wounded men, a system of battlefield evacuation and treatment was developed. It could take many hours for a wounded man to get from the trench into the care of nurses at a casualty clearing station. Not surprisingly, the sight of a nurse there, in her white apron and veil, was like that of an angel.

Seven AANS nurses, Sisters Dorothy Cawood, Clara Deacon, Mary Jane Derrer, Alice Ross-King, Alicia Kelly, Rachael Pratt, and Pearl Corkhill, were awarded the Military Medal, "for acts of gallantry and devotion to duty under fire" while working in casualty clearing stations in France. This was the highest bravery award available to them. But despite enjoying honorary officer status, the nurses were still considered "other ranks" when it came to awards.

During one bombing raid in August 1917, Sister Kelly shielded her patients' heads with enamel wash basins and bedpans. A chaplain found her in a hospital tent, holding a wounded man's hand as the bombs fell. "I couldn't leave my patients," she said simply.

Most of the wounded were eventually passed through to a casualty clearing station, usually sited some kilometres from the front. Here they received treatment from surgeons, and encountered nurses for the first time. From the casualty clearing station the wounded were transported, often by train, to a general hospital, which could care for around 1,000 patients. Men were then evacuated to specialist hospitals in Britain, repatriated home to Australia, or returned to their units in the field.

Nurses on board the hospital ship Karoola accompany badly wounded soldiers on their return to Australia.

Made up of rows of large tents and wooden buildings, 3AGH operated at Abbeville, near Amiens, between May 1917 and May 1918. During periods of heavy fighting, there were numerous surgical cases; at other times there were many casualties from gas, and the hospital became a "gas centre".

"Bluebird" Sister Lynette Crozier applies a dressing to the leg of a wounded French soldier at a mobile hospital south-west of Amiens in France.

Red Cross nurse Sister Duffy acts as anaesthetist during a surgical procedure in a French hospital. Australian nurses often had to learn and exercise new medical skills that they had been restricted from using in their prior civilian careers.

That these women worked their long hours among such surroundings without collapsing spoke volumes for their will power and sense of duty. The place reeked with the odours of blood, antiseptic dressings and unwashed bodies. The nurses saw soldiers in their most pitiful state – wounded, blood-stained, dirty.

Lieutenant Harold Williams, wounded in September 1918

Courage under fire: Sister Rachael Pratt

One night, early in July 1917, Sister Pratt was on duty at a casualty clearing station in Bailleul, France, when a German bomb exploded near her tent. Metal fragments tore into her back and shoulders, puncturing her lung, but she continued to care for her patients right up until she collapsed. She was awarded the Military Medal for her "bravery under fire". Following surgery in Britain, Pratt was posted to various Australian auxiliary hospitals there before returning to Australia at the end of the war. As a result of her war service, she suffered from chronic bronchitis for the rest of her life.

Nursing outposts: India and Greece

I believe it to be awful in India. English nurses could not stand the heat and cholera … that is why they have sent Australians.

Sister Jessie Tomlins

Between 1916 and 1919 more than 500 AANS nurses served in British hospitals in India, where their patients included hundreds of Turkish prisoners of war and wounded British troops. The nurses found the tropical monsoonal climate debilitating.

AANS nurses were also posted to Salonica in Greece, where by 1918 one in five of the nurses in British military hospitals was Australian. They worked mainly in tent hospitals, and most of their patients were suffering from malaria, dysentery, and black water fever. The nurses toiled through hot, mosquito-infested summers, and then had to endure freezing winters, "living in balaclavas and scarves, topcoats and anything else we can get on".

These were challenging locations for the women. With little preparation, they were expected to manage large hospitals, overseeing non–English speaking staff who had very different customs. Many of the nurses felt sidelined from the real action of caring for "our boys" on the Western Front.

"Victorian nurse Christine Ström kept a detailed diary during her time serving in a British hospital in Salonica.